Ударить в грязь лицом

В церемониях открытия Олимпийских игр происходило немало ошибок, да и просто забавных моментов. Вспоминаем наиболее яркие из них.

Санкт-Мориц-1928

Зимние Олимпийские игры в Санкт-Морице, который находится в Швейцарии, были только вторыми по счёту, да и произошло это уже практически век назад. В те времена церемония открытия как таковая включала в себя в основном парад сборных, а развлекательная часть в том виде, в который мы знаем её сейчас, появилась гораздо позднее. Если бы сегодня на суд общественности была представлена церемония, проходившая на льду «Бадрутц Парка», она показалась бы очень и очень скромной. Но, несмотря на всё это, организаторов поджидал неприятный эксцесс: в ночь перед открытием Игр прошёл сильный снегопад, который заставил организаторов начать церемонию на полчаса позже намеченного срока из-за того, что они банально не успели очистить каток от снега.

Санкт-Мориц-1928

Кортина д’Ампеццо-1956

Следующая по времени не столько ошибка организаторов, сколько курьёз произошёл спустя почти три десятка лет. За это время церемонии открытия становились всё пышнее, стадионы, на которых они проводились, – больше, внимание к Играм также увеличивалось, что в том числе способствовало большему освещению Олимпиады в средствах массовой информации. В итоге это и сыграло злую шутку с факелоносцем Гвидо Кароли, который проводил свой этап прямо на олимпийском стадионе. Спортсмен преодолевал путь на коньках и вдруг задел один из телевизионных кабелей, протянутый прямо поперёк его пути. Итогом стало падение, во время которого факел погас, что внесло дополнительную сумятицу в действия организаторов. Огонь, впрочем, вскоре зажгли заново, и в дальнейшем церемония обошлась без накладок.

Кортина д’Ампеццо-1956

Саппоро-1972

В 1972 году зимние Олимпийские игры впервые проводились не в Европе и не в США. При этом сама церемония открытия в Японии прошла без серьёзных помарок, но запомнится она навсегда своей репетицией: один из зрителей, присутствовавших на тренировочном прогоне открытия, обратил внимание на тот факт, что на олимпийском флаге кольца стоят в неправильном порядке, о чём поспешил уведомить организаторов. Те первоначально не восприняли всерьёз эти слова, заявив, что этот флаг используется уже на протяжении многих Олимпиад и ошибки тут быть не может. Однако в итоге обратились к олимпийской хартии, после чего убедились в чудовищной ошибке, которую не обнаруживали на протяжении 20 лет. Получается, что неправильный флаг использовался на всех церемониях открытия в 1950-е и 1960-е годы.

Саппоро-1972

Сеул-1988

Однако не только на зимних Олимпиадах случались курьёзы во время церемоний открытия Игр. Пожалуй, случай в Сеуле даже можно назвать самым неприятным, после которого было принято решение отказаться от традиции выпускать белых голубей. Многие из голубей не стали спешить покидать стадион, удобно устроившись на различных возвышениях на арене, одним из которых оказалась чаша, в которой должен был быть зажжён олимпийский огонь. В итоге, когда нескольких корейских спортсменов подняли на большую высоту на специальной платформе к чаше, у них не было никакой возможности согнать птиц, удобно устроившихся на краю постройки. Когда спустя пару десятков секунд олимпийское пламя загорелось, далеко не все птицы успели покинуть насиженное место, из-за чего в итоге сгорели.

Сеул-1988

Пекин-2008

Церемония открытия, прошедшая в Китае шесть лет назад, по праву неофициально считается самой масштабной, впечатляющей и грандиозной из всех, которые доводилось наблюдать. Однако, несмотря на отточенные часами репетиций действия и слаженность всех участников действа, разворачивавшегося в «Птичьем гнезде», азиатов подвело то, чего никак нельзя было ожидать: а именно техника. Большой жидкокристаллический экран, находящийся прямо в чаше стадиона, в один из моментов, когда на нём должен был идти очередной видеоролик, начал показывать параметры перезагрузки компьютера. Так что даже казавшаяся со всех сторон идеальной церемония не обошлась без маленькой капли дёгтя в бочке мёда.

Пекин-2008

Ванкувер-2010

В Канаде открытие впервые проводилось на закрытом стадионе «Би Си Плэйс» в присутствии почти 60 тысяч зрителей. Техника, в отличие от Пекина, отказала в самый важный момент: из-под пола арены выросли колонны и сложились в костёр, который должны были поджечь Уэйн Грецки, Нэнси Грин, Катрин Лемэй-Доан и Стив Нэш, но один из столбов так и остался под ареной. А не повезло Лемэй-Доан, которой следовало зажечь факел именно с помощью этой колонны. К чести канадцев отметим, что они с достоинством и даже юмором вышли из затруднительного положения: на закрытии организаторы при помощи одного клоуна весело обыграли этот момент.

Ванкувер-2010

Лондон-2012

На последней церемонии открытия, проходившей в столице Великобритании, также не обошлось без забавного случая. Несмотря на все предпринятые меры безопасности одной женщине удалось не просто проникнуть туда, куда доступ запрещён, а вообще оказаться в самой гуще событий, проникнув на поле стадиона во время шествия сборных. Этот факт был замечен довольно быстро: уж больно сильно выделялась женщина в красном на фоне индийской команды, одетой совершенно по-иному. Данный факт вызвал бурное обсуждение в прессе, но это и не мудрено: грош цена мерам предосторожности, если секьюрити не могут уследить за тем, кто проникает прямо посреди церемонии открытия к спортсменам на глазах у миллиардов людей по всему земному шару.

Лондон-2012

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The Olympic Games is a major international multi-sport event. During its history, both the Summer and Winter Games have been a subject of scandals and controversies, including the use of performance enhancing drugs.

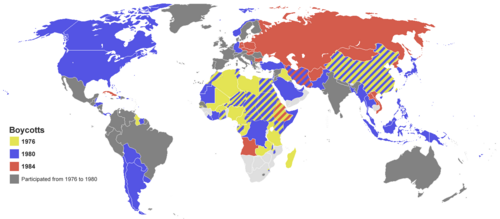

Some countries have boycotted the Games on various occasions, either as a protest against the International Olympic Committee or to protest racial discrimination in or the contemporary politics of other participants. After both World Wars, the defeated countries were not invited. Other controversies include doping programs, decisions by referees and gestures made by athletes.

Summer Olympics[edit]

1908 Summer Olympics – London, England, United Kingdom[edit]

- Grand Duchy of Finland competed separately from the Russian Empire, but was not allowed to display the Finnish flag.[1]

- In the men’s 400 metres, American winner John Carpenter was disqualified for blocking British athlete Wyndham Halswelle in a manoeuvre that was legal under American rules but prohibited by the British rules under which the race was run. As a result of the disqualification, a second final race was ordered. Halswelle was to face the other two finalists William Robbins and John Taylor, but both were from the United States and decided not to contest the repeat of the final to protest the judges’ decision. Halswelle was thus the only medallist in the 400 metres, a race which became the only walkover victory in Olympic history. Taylor later ran on the Gold medal-winning U.S. team for the now-defunct Medley Relay, becoming the first African American medallist.[2]

1912 Summer Olympics – Stockholm, Sweden[edit]

- American athlete Jim Thorpe was stripped of his gold medals in the decathlon and pentathlon after it was learned that he had played professional minor league baseball three years earlier.[3] In solidarity, the decathlon silver medalist, Hugo Wieslander, refused to accept the medals when they were offered to him.[4] The gold medals were restored to Thorpe’s children in 1983, 30 years after his death.[3]

1916 Summer Olympics (not held due to World War I)[edit]

- The 1916 Summer Olympics were to have been held in Berlin, German Empire, but were cancelled because of the outbreak of World War I.

1920 Summer Olympics – Antwerp, Belgium[edit]

- Budapest had initially been selected over Amsterdam and Lyon to host the Games, but as the Austro-Hungarian Empire had been a German ally in World War I, the French-dominated International Olympic Committee transferred the Games to Antwerp in April 1919.

- Austria, Bulgaria, Germany, Hungary, and Turkey were not invited to the Games, being the successor states of the Central Powers which were defeated in World War I.[1]

1924 Summer Olympics – Paris, France[edit]

- Germany was again not invited to the Games.[5]

1932 Summer Olympics – Los Angeles, California, United States[edit]

- Nine-time Finnish Olympic gold medallist Paavo Nurmi was found to be a professional athlete and banned from running in the Games. The main orchestrators of the ban were the Swedish officials that were the core of the IOC bureaucracy, including IOC president Sigfrid Edström, who claimed that Nurmi had received too much money for his travel expenses. Nurmi did, however, travel to Los Angeles and kept training at the Olympic Village. Despite pleas from all the other entrants of the marathon, he was not allowed to compete at the Games. This incident, in part, led to Finland refusing to participate in the traditional Finland-Sweden athletics international annual event until 1939.

- After winning the silver in equestrian dressage, Swedish rider Bertil Sandström was demoted to last for clicking to his horse to win encouragement. He asserted that it was a creaking saddle making the sounds.

1936 Summer Olympics – Berlin, Germany[edit]

- In 1931, the International Olympic Committee (IOC) selected the German capital city Berlin as the host city of the 1936 Summer Olympics. However, following Adolf Hitler’s rise to power in 1933, the plans for the Olympic Games became entangled with the politics of the Nazi regime. Hitler regarded the event as ‘his’ Olympics and sought to exploit the Games for propaganda purposes, with the aim of showcasing post-First World War Germany. In 1936, a number of prominent politicians and organizations called for a boycott of the Summer Olympics, while other campaigners called for the games to be relocated.[6][7]

- Lithuania was not invited by Germany due to the Memelland/Klaipėda region controversy.[citation needed]

- The Popular Front government of the Second Spanish Republic decided to boycott the Berlin Games entirely and, together with labour and socialist groups around the world, organized an alternative event, the People’s Olympiad. The event did not take place however; just as the Games were about to begin the Spanish Civil War broke out and the People’s Olympiad was canceled.

- In the United States, there was considerable debate about boycotting the Games.[8] A leading advocate of a boycott was U.S. athlete and politician Ernest Lee Jahncke, the son of a German immigrant, who was an IOC member before being expelled from the IOC for his views.

- International concern surrounded the ruling German National Socialists’ ideology of racial superiority and its application at an international event such as the Olympics.[7][9] In 1934 Avery Brundage undertook a visit to Germany to investigate the treatment of Jews. When he returned, he reported, «I was given positive assurance in writing … that there will be no discrimination against Jews. You can’t ask more than that and I think the guarantee will be fulfilled.»[10] In the event, a number of record-holding German athletes were excluded from competing at Berlin for being racially undesirable, including Lilli Henoch,[11] Gretel Bergmann[12][13] and Wolfgang Fürstner.[14] The only Jewish athlete to compete on the German team was fencer Helene Mayer.

- Hitler’s decision not to shake hands with American long-jump medal winner Jesse Owens has been widely interpreted as a snub of an African American; however some commentators have noted that Hitler missed all medal presentations after the first day as he only wished to shake hands with German victors.[15][16] Owens himself was reported to have been magnanimous when he mentioned Hitler.[17] After the Games however, Owens was not personally honoured by President Franklin D. Roosevelt.[18]

- The Irish Olympic Council boycotted the games as the IAAF had expelled the National Athletic and Cycling Association for refusing to restrict itself to the Irish Free State rather than the island of Ireland.[19]

- In the cycling match sprint final, German Toni Merkens fouled Dutch Arie van Vliet. Instead of disqualification, Merkens was fined 100 German reichsmarks and kept the gold medal.[citation needed]

- In one of the football quarter-finals, Peru beat Austria 4–2 but Austria went through very controversial circumstances. As a sign of protest the complete Olympic delegations of Peru and Colombia left Germany.[citation needed]

- French and Canadian Olympians gave what appeared to be the Nazi salute at the opening ceremony, although they may have been performing the Olympic salute, which is similar, as both are based on the Roman salute.[citation needed]

1940 and 1944 Summer Olympics (not held due to World War II)[edit]

- The 1940 Summer Olympics were scheduled to be held in Tokyo, Japan, but were cancelled due to the outbreak of the Second Sino-Japanese War. The government of Japan abandoned its support for the 1940 Games in July 1938.[20] The IOC then awarded the Games to Helsinki, Finland, the runner-up in the original bidding process, but the Games were not held due to the Winter War. Ultimately, the Olympic Games were suspended indefinitely following the outbreak of World War II and did not resume until the London Games of 1948.

1948 Summer Olympics – London, England, United Kingdom[edit]

- The two major Axis powers of World War II, Germany and Japan, were suspended from the Olympics, though Italy, a former German ally, participated.[1] German and Japanese athletes were allowed to compete again at the 1952 Olympics.

- The Soviet Union was invited but chose not to send any athletes, sending observers instead to prepare for the 1952 Olympics.

1956 Summer Olympics – Melbourne, Australia and Stockholm, Sweden[edit]

- Eight countries boycotted the Games for three different reasons. Cambodia, Egypt, Iraq, and Lebanon announced that they would not participate in response to the Suez Crisis during which Egypt had been invaded by Israel, the United Kingdom, and France after Egypt had nationalized the Suez Canal.[1] The Netherlands, Spain, and Switzerland withdrew to protest the Soviet Union’s invasion of Hungary during the 1956 Hungarian Revolution and the Soviet presence at the Games.[1] Less than two weeks before the Opening Ceremony, the People’s Republic of China also chose to boycott the event, protesting the Republic of China (Taiwan) being allowed to compete (under the name «Formosa»).

- The political frustrations between the Soviet Union and Hungary boiled over at the games themselves when the two men’s water polo teams met for the semi-final. The players became increasingly violent towards one another as the game progressed, while many spectators were prevented from rioting only by the sudden appearance of the police.[21] The match became known as the Blood in the Water match.[22][23]

- The advent of the state-sponsored «full-time amateur athlete» of the Eastern Bloc countries further eroded the ideology of the pure amateur, as it put the self-financed amateurs of the Western countries at a disadvantage. The Soviet Union entered teams of athletes who were all nominally students, soldiers, or working in a profession, but many of whom were in reality paid by the state to train on a full-time basis.[24] Nevertheless, the IOC held to the traditional rules regarding amateurism for athletes from non-Communist countries.[25]

- Due to quarantine issues, the equestrian events were held in Stockholm, Sweden.

1964 Summer Olympics – Tokyo, Japan[edit]

- Indonesia and North Korea withdrew after the IOC decision to ban teams that took part in the 1963 Games of the New Emerging Forces and a three-year violent conflict, the Indonesia–Malaysia confrontation.[1]

- South Africa was suspended from the Olympics due to its apartheid policies.[1] The suspension would be lifted in 1992.

1968 Summer Olympics – Mexico City, Mexico[edit]

- 1968 Olympics Black Power salute: Tommie Smith and John Carlos, two black athletes who finished the men’s 200-metre race first and third respectively, performed the «Power to the People» salute during the United States national anthem. Peter Norman, a white Australian who finished in second place, wore a human rights badge in solidarity, and was heavily criticised upon returning to Australia. George Foreman, the Olympic boxing heavyweight champion, who on the contrary waved the American flag, became an «Uncle Tom»-like outcast for many years.

- Věra Čáslavská, in protest to the 1968 Soviet-led invasion of Czechoslovakia and the controversial decision by the judges on the Balance Beam and Floor, turned her head down and away from the Soviet flag whilst the anthem played during the medal ceremony. She returned home as a heroine of the Czechoslovak people, but was made an outcast by the Soviet dominated government.

- Students in Mexico City tried to make use of the media attention for their country to protest the authoritarian Mexican government. The government reacted with violence, culminating in the Tlatelolco Massacre ten days before the Games began and more than two thousand protesters were shot at by government forces.

1972 Summer Olympics – Munich, West Germany[edit]

- The Munich massacre occurred, when members of the Israeli Olympic team were taken hostage by the Palestinian terrorist group Black September. Eleven athletes, coaches and judges were murdered by the terrorists.

- Rhodesia was banned from participating in the Olympics as the result of a 36 to 31 vote by the IOC held four days before the opening ceremonies. African countries had threatened to boycott the Munich games had the white-minority-ruled regime been permitted to send a team. The ban occurred over the objections of IOC president Avery Brundage who, in his speech following the Munich massacre, controversially compared the anti-Rhodesia campaign to the terrorist attack on the Olympic village.[26] (see Rhodesia at the Olympics)

- In the controversial gold medal basketball game, the US team appeared to win the gold medal game against the Soviet team, but the final three seconds were replayed three times until the Soviets won.[27]

- The 1972 Olympics Black Power salute, also known as the Forgotten Salute.

- At the end of the men’s Marathon, a German impostor entered the stadium to the cheers of the stadium ahead of the actual winner, Frank Shorter of the United States. During the American Broadcasting Company coverage of the event, the guest commentator, writer Erich Segal famously called to Shorter «It’s a fraud, Frank.»[28][29]

- In the men’s field hockey final, Michael Krause’s goal in the 60th minute gave the host West German team a 1–0 victory over the defending champion Pakistan. Pakistan’s players complained about some of the umpiring and disagreed that Krause’s goal was good. After the game, Pakistani fans ran onto the field in rage; some players and fans dumped water on Belgium’s Rene Frank, the head of the sport’s international governing body. During the medals ceremony, the players staged protests, some of them turning their backs to the West German flag and handling their silver medals disrespectfully. According to the story in the Washington Post, the team’s manager, G.R. Chaudhry, said that his team thought the outcome had been «pre-planned» by the officials, Horacio Servetto of Argentina and Richard Jewell of Australia.

1976 Summer Olympics – Montreal, Canada[edit]

- In protest against the New Zealand national rugby union team’s 1976 tour of South Africa, controversial due to the regime’s apartheid policies, Afghanistan, Albania, Burma, El Salvador, Guyana, Iraq, Sri Lanka, Syria and Tanzania, led a boycott of twenty-two African nations after the IOC refused to ban New Zealand from participating. Some of the teams withdrew after the first day.[1][30][31] The controversy prevented a much anticipated meeting between Tanzanian Filbert Bayi—the former world record holder in both the 1500 metres and the mile run—and New Zealand’s John Walker—who had surpassed both records to become the world record holder in both events. Walker went on to win the gold medal in the 1500 metres.[32]

- Canada initially refused to allow the Republic of China’s team (Taiwan) into the country as Canada did not recognize Taiwan as a nation. Canada’s decision was in violation of its agreement with the IOC to allow all recognized teams. Canada agreed to allow the Taiwanese athletes into the country if they did not compete under the name or flag of the Republic of China. This led to protests and a threatened boycott by other countries including the US, but these came to naught after the IOC acquiesced to the Canadian demand which, in turn, led Taiwan to boycott the Games. The People’s Republic of China also continued its boycott over the failure of the IOC to recognize its team as the sole representative of China.[33]

- The various boycotts resulted in only 92 countries participating, down from 121 in 1972 and the lowest number since the 1960 Rome Games in which 80 states competed.

- Soviet modern pentathlete Boris Onishchenko was found to have used an épée which had a pushbutton on the pommel in the fencing portion of the pentathlon event. This button, when activated, would cause the electronic scoring system to register a hit whether or not the épée had actually connected with the target area of his opponent. As a result of this discovery, he and the Soviet pentathlon team were disqualified.[34]

- Quebec, the host province, incurred $1.5 billion in debt, which was not paid off until December 2006. The Mayor of Montreal Jean Drapeau had famously said: «The Olympics can no more lose money than a man can have a baby.»[35]

1980 Summer Olympics – Moscow, Soviet Union[edit]

- 1980 Summer Olympics boycott: U.S. President Jimmy Carter instigated a boycott of the games to protest the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, as the Games were held in Moscow, the capital of the Soviet Union. Many nations refused to participate in the Games. The exact number of boycotting nations is difficult to determine, as a total of 66 eligible countries did not participate, but some of those countries withdrew due to financial hardships, only claiming to join the boycott to avoid embarrassment.[citation needed] Iran also boycotted the Moscow Games owing to Ayatollah Khomeini’s support for the Islamic Conference’s condemnation of the invasion of Afghanistan.[36] Only 80 countries participated in the Moscow games, fewer than the 92 that had joined the 1976 games and the lowest number since the 1960 Rome Games which had also featured 80 countries. A substitute event, titled the Liberty Bell Classic, often referred to as Olympic Boycott Games, was held at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia by 29 of the boycotting countries.

- A 1989 report by a committee of the Australian Senate claimed that «there is hardly a medal winner at the Moscow Games, certainly not a gold medal winner…who is not on one sort of drug or another: usually several kinds. The Moscow Games might well have been called the Chemists’ Games».[37] A member of the IOC Medical Commission, Manfred Donike, privately ran additional tests with a new technique for identifying abnormal levels of testosterone by measuring its ratio to epitestosterone in urine. Twenty percent of the specimens he tested, including those from sixteen gold medalists would have resulted in disciplinary proceedings had the tests been official. The results of Donike’s unofficial tests later convinced the IOC to add his new technique to their testing protocols.[38] The first documented case of «blood doping» occurred at the 1980 Summer Olympics as a runner was transfused with two pints of blood before winning medals in the 5000 m and 10,000 m.[39]

- Polish gold medallist pole vaulter Władysław Kozakiewicz showed an obscene bras d’honneur gesture in all four directions to the jeering Soviet public, causing an international scandal and almost losing his medal as a result. There were numerous incidents and accusations of Soviet officials using their authority to negate marks by opponents to the point that IAAF officials found the need to look over the officials’ shoulders to try to keep the events fair. There were also accusations of opening stadium gates to advantage Soviet athletes, and causing other disturbances to opposing athletes.[40][41][42][43][44]

1984 Summer Olympics – Los Angeles, California, United States[edit]

- 1984 Summer Olympics boycott: The Soviet Union and fourteen of its allies boycotted the 1984 Games held in Los Angeles, United States, citing a lack of security for their athletes as the official reason. The decision was regarded as a response to the United States-led boycott issued against the Moscow Olympics four years earlier.[45] The Eastern Bloc organized its own event, the Friendship Games, instead. The fact that Romania, a Warsaw Pact country, opted to compete despite Soviet demands led to a warm reception of the Romanian team by the United States. When the Romanian athletes entered during the opening ceremonies, they received a standing ovation from the spectators.[46][47] For different reasons, Iran[48] and Libya[49] also boycotted the Games.[50]

- The men’s light heavyweight boxing match between Kevin Barry and Evander Holyfield ended in controversy, when referee Grigorije Novičić of Yugoslavia disqualified a clearly dominant Holyfield. Barry eventually won the silver medal, with Holyfield settling for bronze.[51]

1988 Summer Olympics – Seoul, Republic of Korea[edit]

- The games were boycotted by North Korea and its ally, Cuba. Ethiopia, Albania and the Seychelles did not respond to the invitations sent by the IOC.[52] Nicaragua did not participate due to athletic and financial considerations.[53] The participation of Madagascar had been expected, and their team was expected at the opening ceremony of 160 nations but the country withdrew because of financial reasons.[54]

- Canadian sprinter Ben Johnson was stripped of his gold medal for the 100 metres when he tested positive for stanozolol after the event.[55]

- In a highly controversial 3–2 judge’s decision, South Korean boxer Park Si-Hun defeated American Roy Jones Jr., despite Jones pummelling Park for three rounds, landing 86 punches to Park’s 32. Allegedly, Park himself apologized to Jones afterward. One judge shortly thereafter admitted the decision was a mistake, and all three judges voting against Jones were eventually suspended. The official IOC investigation concluding in 1997 found that three of the judges had been wined and dined by South Korean officials. This led to calls for Jones to be awarded a gold medal, but the IOC still officially stands by the decision, despite the allegations.[56]

- American diver Greg Louganis suffered a concussion after he struck his head on the springboard during the preliminary rounds. He completed the preliminaries despite his injury, earning the highest single score of the qualifying round for his next dive and repeated the dive during the finals, earning the gold medal by a margin of 25 points. Louganis had been diagnosed HIV-positive six months prior to the games—a diagnosis that was not publicly disclosed until 1995. This led some to question Louganis’ decision not to disclose his HIV status during the Games, even though blood in a pool posed no risk.[57]

1992 Summer Olympics – Barcelona, Spain[edit]

- Three British athletes, sprinter Jason Livingston, weightlifters Andrew Davies and Andrew Saxton, were sent home after being tested positive for Anabolic steroid and Clenbuterol.[58][59]

- Russian weightlifter Ibragim Samadov was disqualified for a protest after he refused to accept the bronze medal at the medal ceremony. He was eventually banned for life.[60]

- In the final of the men’s 10,000 m Moroccan Khalid Skah was racing Kenyan Richard Chelimo for the gold medal; with three laps remaining they both lapped Moroccan Hammou Boutayeb. Even though he was lapped he stayed with the leaders, slowing down the Kenyan and inciting the crowd to jeer.[61] Initially Skah was disqualified for receiving assistance from a lapped runner, but, after an appeal by the Moroccan team to the IAAF, he was reinstated and his gold medal stood.[61][62]

1996 Summer Olympics – Atlanta, Georgia, USA[edit]

- The 1996 Olympics were marred by the Centennial Olympic Park bombing.

- A gold medal boxing match in which Daniel Petrov from Bulgaria won against Mansueto Velasco from the Philippines was described as robbery in the Philippines. One media outlet claimed that it appeared that the judges were pressing the buttons on their electronic scoring equipment for the wrong boxer.[63] However, neutral commentators stated that «[i]n Atlanta [Petrov] proved his supremacy beyond doubt and was never really troubled in any of his 4 fights» and that «Velasco’s attempt to be the Philippines’ first Olympic champion faltered from the beginning and [Petrov] was a clear winner by 19 points to 6.»[64] The New York Times reported that «Daniel Petrov Bojilov … dominated Mansueto Velasco of the Philippines, 19-6,» but acknowledged that «the Filipino deserved more points.»[65]

2000 Summer Olympics – Sydney, Australia[edit]

- In December 2007 American track star Marion Jones was stripped of five medals after admitting to anabolic steroid use. Jones had won three gold medals (100-metre sprint, 200-metre sprint and 4×400 relay) and two bronze medals (long jump and 4×100 relay).[66] The IOC action also officially disqualified Jones from her fifth-place finish in the Long Jump at the 2004 Summer Olympics.[66] At the time of her admission and subsequent guilty plea, Jones was one of the most famous athletes to be linked to the BALCO scandal.[67] The case against BALCO covered more than 20 top level athletes, including Jones’s ex-husband, shot putter C.J. Hunter, and 100 m sprinter Tim Montgomery, the father of Jones’ first child.

- In the Women’s artistic gymnastics, Australian competitor Allana Slater complained that the vault was set too low. The vault was measured and found to be 5 centimetres lower than it should have been. A number of the gymnasts made unusual errors, including American Elise Ray, who missed the vault completely in her warm-up, and Briton Annika Reeder, who fell and had to be carried off the mat after being injured.

- Romanian Andreea Răducan became the first gymnast to be stripped of a medal after testing positive for pseudoephedrine, at the time a prohibited substance.[68] Răducan, 16, took Nurofen, a common over-the-counter medicine, to help treat a fever. The Romanian team doctor who gave her the medication was expelled from the Games and suspended for four years. The gold medal was finally awarded to Răducan’s teammate Simona Amânar. Răducan was allowed to keep her other medals, a gold from the team competition and a silver from the vault.

- Chinese gymnast Dong Fangxiao was stripped of a bronze medal in April 2010. Investigations by the sport’s governing body (FIG) found that she was only 14 at the 2000 Games. (To be eligible the gymnastic athletes must turn 16 during the Olympic year). FIG recommended the IOC take the medal back as her scores aided China in winning the team bronze. The US women’s team, who had come fourth in the event, moved up to third.[69]

2004 Summer Olympics – Athens, Greece[edit]

- In artistic gymnastics, judging errors and miscalculation of points in two of the three events led to a revision of the gymnastics Code of Points.[70] The South Korean team contested Tae-Young’s parallel bars score after judges misidentified one of the elements of his routine. Further problems occurred in the men’s horizontal bar competition. After performing a routine with six release skills in the high bar event final (including four in a row – three variations of Tkatchev releases and a Gienger), the judges posted a score of 9.725, placing Nemov in third position with several athletes still to compete. This was actually a fair judging decision because he took a big step on landing which was a two-tenths deduction.[citation needed] The crowd became unruly on seeing the results and interrupted the competition for almost fifteen minutes. Influenced by the crowd’s fierce reaction, the judges reevaluated the routine and inflated Nemov’s score to 9.762.[71][72]

- While leading in the men’s marathon with less than 10 kilometres to go, Brazilian runner Vanderlei de Lima was attacked by de-frocked Irish priest Neil Horan and dragged into the crowd. De Lima recovered to take bronze, and was later awarded the Pierre de Coubertin medal for sportsmanship.[73]

- Hungarian fencing official Joszef Hidasi was suspended for two years by the FIE after committing six errors in favour of Italy during the gold-medal match in men’s team foil, denying the Chinese opponent the gold medal.[74]

- Canadian men’s rowing pair Chris Jarvis and David Calder were disqualified in the semi-final round after they crossed into the lane belonging to the South African team, interfering with their progress. The Canadians appealed unsuccessfully to the Court of Arbitration for Sport.[citation needed]

- In the women’s 100m hurdles, Canadian sprinter Perdita Felicien stepped on the first hurdle, tumbling to the ground and taking Russian Irina Shevchenko with her. The Russian team filed an unsuccessful protest, pushing the medal ceremony back a day. Track officials debated for about two hours before rejecting the Russian arguments. The race was won by the United States’ Joanna Hayes in Olympic-record time.[citation needed]

- Iranian judoka Arash Miresmaili was disqualified after he was found to be overweight before a judo bout against Israeli Ehud Vaks. He had gone on an eating binge the night before in a protest against the IOC’s recognition of the state of Israel. It was reported that Iranian Olympic team chairman Nassrollah Sajadi had suggested that the Iranian government should give him $115,000 (the amount he would have received if he had won the gold medal) as a reward for his actions. Then-President of Iran, Mohammad Khatami, who was reported to have said that Arash’s refusal to fight the Israeli would be «recorded in the history of Iranian glories», stated that the nation considered him to be «the champion of the 2004 Olympic Games.»[citation needed]

- Pelle Svensson, a former two-time world champion (Greco-Roman 100 kg class) and member of board of FILA from 1990 to 2007, has described FILA as an inherently corrupt organization.[75] During the Games, Svensson served as chairman of the disciplinary committee of FILA.[75] As he was watching the final in the men’s Greco-Roman wrestling 84 kg class between Alexei Michine from Russia and Ara Abrahamian from Sweden, Svensson witnessed how the Russian team leader Mikhail Mamiashvili was giving signs to the referee.[75] When Svensson approached the official and informed him that this was not allowed according to the rules, Mamiashvili responded by saying: «you should know that this may lead to your death».[75] Svensson later found proof that the Romanian referee was bribed (according to Svensson the referee had received over one million Swedish krona).[75]

2008 Summer Olympics – Beijing, China[edit]

- Players for the men’s basketball teams posed for a pre-Olympic newspaper advertisement in popular Spanish daily Marca, in which they were pictured pulling back the skin on either side of their eyes, narrowing them in order to mimic the stereotypes of thin Asian eyes.[76]

- Swedish wrestler Ara Abrahamian placed his bronze medal onto the floor immediately after it was placed around his neck in protest at his loss to Italian Andrea Minguzzi in the semifinals of the men’s 84kg Greco-Roman wrestling event.[77] He was subsequently disqualified by the IOC, although his bronze medal was not awarded to Chinese wrestler Ma Sanyi, who finished fifth.

- Questions have been raised about the ages of two Chinese female gymnasts, He Kexin and Jiang Yuyuan. This is due partly to their youthful appearance, as well as a speech in 2007 by Chinese director of general administration for sport Liu Peng.[78]

- Norway’s last-second goal against South Korea in the handball semifinals put it through to the gold medal game, despite the ball possibly failing to have fully crossed the goal line prior to time expiring. The South Koreans protested and requested that the game continue into overtime. The IHF has confirmed the results of the match.[79]

- Cuban taekwondo competitor Ángel Matos was banned for life from any international taekwondo events after kicking a referee in the face. Matos attacked the referee after he disqualified Matos for violating the time limit on an injury timeout.[80] He then punched another official.[81]

- China was criticized for their state run athlete training program.[82][83]

- By April 2017, the 2008 Summer Olympics had the most (50) Olympic medals stripped for doping violations. The leading country is Russia with 14 medals stripped.

2012 Summer Olympics – London, England, United Kingdom[edit]

- The North Korean women’s football team delayed their game against Colombia for an hour after the players were introduced on the jumbo screen with the Flag of South Korea.[84]

- Greek triple and long jumper Paraskevi Papachristou was expelled by the Greek Olympic Committee after posting a racially insensitive comment on social media.[85][86]

- South Korean fencer Shin A-lam lost the semifinal match in the individual épée to Germany’s Britta Heidemann, after a timekeeping error allowed Heidemann to score the winning point before time expired. Shin A-lam remained on the piste for over an hour while her appeal was considered,[87][88] but the appeal was ultimately rejected and Germany advanced to play for the gold medal. Shin A-Lam was offered a consolation medal but declined the offer.

- In the men’s team artistic gymnastics, Japan was promoted to the silver medal position after successfully lodging an appeal over Kōhei Uchimura’s final pommel horse performance. His fall on the last piece of apparatus had initially relegated the Japanese to fourth, and elevated host Great Britain to silver, and Ukraine to bronze. Although the decision to upgrade the Japanese score was greeted with boos in the arena, the teams involved accepted the correction.[89]

- Swiss footballer Michel Morganella was expelled from the Olympics after a racist comment on Twitter about Koreans after Switzerland lost 2–1 to South Korea.

- The men’s light flyweight boxing gold medal match between Kaeo Pongprayoon of Thailand and Zou Shiming of China was marred by controversy. Zou, the Chinese fighter, won on a controversial decision. Poingprayoon was hit with a two-point penalty for an unclear offence with 9 seconds left in the bout to give the Chinese boxer the victory.

- During the semi-final women’s football match between Canada and the United States, a time-wasting call was made against the Canadian goalkeeper, Erin McLeod, when she held the ball longer than the allowed six seconds. This violation is called in international play, and is intended to be used during instances of time-wasting.[90] As a result, the American side was awarded an indirect free-kick in the box. On the ensuing play, Canada was penalized for a handball in the penalty box, with the American team being awarded a penalty kick, which Abby Wambach converted to tie the game at 3–3. The Americans went on to win the match in extra time, advancing to the gold medal game.[91][92] FIFA responded by stating that the refereeing decisions were correct.[93][94][95]

- The badminton women’s doubles tournament became embroiled in controversy during the group stage when eight players (both pairs from South Korea and one pair each from China and Indonesia) were ejected from the tournament by the Badminton World Federation after being found guilty of «not using best efforts» and «conducting oneself in a manner that is clearly abusive or detrimental to the sport» by playing to lose matches in order to manipulate the draw for the knockout stage.[96] In one match, both teams made a series of basic errors, and in another the longest rally was just four shots.

- In a men’s bantamweight early round boxing match, Japanese boxer Satoshi Shimizu floored Magomed Abdulhamidov of Azerbaijan six times in the third round. The referee, Ishanguly Meretnyyazov of Turkmenistan, never scored a count in each of the six knockdowns and let the fight continue. Meretnyyazov claimed they were slips, and even fixed Abdulhamidov’s headgear during the affair. Abdulhamidov had to be helped to his corner following the round. The fight was scored 22–17 in favour of Abdulhamidov. AIBA, the governing body for Olympic boxing, overturned the result following an appeal by Japan.[97]

- By April 2017, the Olympics had 29 Olympic medals stripped for doping violations. The leading country is Russia with 13 medals stripped.

2016 Summer Olympics – Rio de Janeiro, Brazil[edit]

- Russian doping scandal and participation restrictions —

- During a women’s volleyball qualification tournament, a match between Japan and Thailand caused controversy after the Thai team were given two red cards during the final set.[98][99] Japan finished the tournament third and qualified for the Olympics, while Thailand finished fifth and did not qualify. The FIVB declined to review the match.[100]

- Islam El Shehaby, an Egyptian judoka, refused to shake hands and bow to his opponent after being defeated by the Israeli Or Sasson.[101]

- Four U.S. swimmers, Ryan Lochte, Jimmy Feigen, Gunnar Bentz, and Jack Conger, allegedly vandalized a gas station bathroom, and were forced to pay for the damage by two security men who brandished a gun at the swimmers before a translator arrived. The swimmers later claimed to have been pulled over and robbed by gunmen wearing police uniforms. The Federal Police of Brazil detained Feigen, Bentz, and Conger (Lochte having already left the country) after it was determined that the swimmers had made false reports to the police of being robbed.[102] All of the swimmers involved would receive various punishments and suspensions relating to their conduct during the incident by USA Swimming and USOC.

- During the weightlifting tournament, Iran’s Behdad Salimi broke the world record in the snatch weightlifting of the Men’s over 105-kilogram class, but was later disqualified in the clean and jerk stage.[citation needed] The Iranian National Olympic Committee filed an appeal to the Court of Arbitration for Sport against the International Weightlifting Federation (IWF), and the IWF’s website was hacked by protestors.[103][104][105] The CAS dismissed the appeal due to a lack of evidence that the disqualification was made in bad faith.[106][107]

- Nine Australian athletes had their passports seized by Brazilian police and were fined R$10,000 (US$3,000) after it was revealed they had falsified their credentials in order to watch a basketball game between Serbia and Australia.[108]

- During the second bronze medal match between Uzbekistan’s Ikhtiyor Navruzov and Mongolia’s Ganzorigiin Mandakhnaran in the 65 kg freestyle wrestling, Mandakhnaran held a lead of 7-6 near the end of the match and began celebrating before it had concluded. In response, Ikhtiyor was awarded a penalty point for Mandakhnaran «failing to engage» during the end of the match, which resulted in a 7-7 draw. Ikhtiyor won the game and the bronze due to being the last to score. The Mongolian coaches protested the point, which could not be challenged, by stripping in front of the judges on the mat, resulting in a shoe being sent into the judges’ table. Ikhtiyor was awarded a second penalty point as the coaches were escorted away from the mat, leading to the final score being 7–8.[109][110][111]

- Controversy surrounded the new judging system in boxing; the new counting system had five judges who judged each bout, and a computer randomly selected three whose scores are counted. Traditionally, judges would use a computer scoring system to count each punch landed, but in 2016 the winner of each round was awarded 10 points and the loser a lower number, based on criteria which includes the quality of punches landed, effective aggression and tactical superiority.[112] Two results in particular attracted controversy, both involving Russian athletes whose victories were put in question: the defeat of Vasily Levit by Russian Evgeny Tishchenko in the men’s heavyweight gold-medal fight[113] and the defeat of Michael Conlan by Vladimir Nikitin in the men’s bantamweight quarter-final, after which Conlan accused AIBA and the Russian team of cheating, even tweeting to President of Russia Vladimir Putin «Hey Vlad, How much did they charge you bro??».[112][114] The AIBA removed an unspecified number of judges and referees following the controversy, stating that they «determined that less than a handful of the decisions were not at the level expected» and «that the concerned referees and judges will no longer officiate at the Rio 2016 Olympic Games»; however, the original decisions stood.[115][116]

- In December 2016, Russian boxer Misha Aloyan was stripped of the silver medal in 52 kg boxing at the Games for testing positive for tuaminoheptane.[117]

2020 Summer Olympics – Tokyo, Japan[edit]

- In the wake of the global COVID-19 pandemic, the Games were postponed for the first time in the 124-year history of the modern Olympics.[118] The Games were held in July and August 2021, despite many concerns that the Delta variant of COVID-19 posed a serious threat.[citation needed]

- Fethi Nourine, an Algerian judoka competing in the men’s 73kg class, was sent home from the Tokyo Olympics after he withdrew from the competition after refusing to compete against an Israeli opponent, Tohar Butbul.[119] The International Judo Federation (IJF) announced the immediate suspension of Nourine and his coach on 24 July 2021, pending a further investigation, while the Algerian Olympic Committee revoked their accreditation, and sent Nourine and his coach back home to Algeria.[120] Nourine and coach Amar Benikhlef were banned from international competition for ten years.[121]

- Oceania’s Rhythmic Gymnastics qualification for the Tokyo Olympics was conducted with severe breaches that resulted in change of ranking for Olympic Nomination and Selection. A 1.5-year-long investigation by Gymnastics Ethics Foundation found serious misconducts by qualification event’s organisers, administrators and officials. As a result Gymnastics Australia, Oceania Gymnastics Union, an administrator and two judges were sanctioned.[122]

Winter Olympics[edit]

1928 Winter Olympics – St Moritz, Switzerland[edit]

- In the 10,000-meter speed skating race, American Irving Jaffee was leading the competition, having outskated Norwegian defending world champion Bernt Evensen in their heat, when rising temperatures thawed the ice.[123] In a controversial ruling, the Norwegian referee canceled the entire competition. Although the IOC reversed the referee’s decision and awarded Jaffee the gold medal, the International Skating Union later overruled the IOC and restored the ruling.[124] Evensen, for his part, publicly said that Jaffee should be awarded the gold medal, but that never happened.

1968 Winter Olympics – Grenoble, France[edit]

- French skier Jean-Claude Killy achieved a clean sweep of the then-three alpine skiing medals at Grenoble, but only after what the IOC bills as the «greatest controversy in the history of the Winter Olympics.»[125] The slalom run was held in poor visibility and Austrian skier Karl Schranz claimed a course patrolman crossed his path during the slalom race, causing him to stop. Schranz was given a restart and posted the fastest time. A Jury of Appeal then reviewed the television footage, declared that Schranz had missed a gate on the upper part of the first run, annulled his repeat run time, and gave the medal to Killy.[126]

- Three East German competitors in the women’s luge event were disqualified for illegally heating their runners prior to each run.[citation needed]

1972 Winter Olympics – Sapporo, Japan[edit]

- Austrian skier Karl Schranz, a vocal critic of then-IOC president Avery Brundage and reportedly earning $50,000 a year at the time,[127] was singled out for his status as a covertly professional athlete, notably for his relationship with the ski manufacturer Kneissl, and ejected from the games. Schranz’s case was particularly high-profile because of the disqualification controversy centring on him at the 1968 games and Schranz’s subsequent dominance of alpine skiing in the Skiing World Cups of 1969 and 1970. Brundage’s twenty-year reign as President of the IOC ended six months later and subsequent presidents have been limited to terms of eight years, renewable once for four years.

1976 Winter Olympics – Innsbruck, Austria[edit]

- The chosen location for the 1976 Winter Olympics was originally Denver, Colorado. However, after the city’s voters rejected partially funding the Games, they were relocated to Innsbruck, Austria. Innsbruck previously hosted the 1964 Games.[128]

1980 Winter Olympics – Lake Placid, New York, United States[edit]

- Taiwan (The Republic of China) did not participate in the Games over the IOC’s recognition of the People’s Republic of China as «China», and its request for Taiwan to compete as «Chinese Taipei». Taiwan missed the 1976 Montreal Summer Games and 1980 Moscow Summer Games for the same reason. It returned to the Games in 1984.[129]

1994 Winter Olympics – Lillehammer, Norway[edit]

- Jeff Gillooly, the ex-husband of U.S. figure skater Tonya Harding, arranged for an attack on her closest American rival, Nancy Kerrigan, a month before the start of the Games. Both women competed, with Kerrigan winning the silver and Harding performing poorly. Harding was later banned for life both from competing in USFSA-sanctioned events and from becoming a sanctioned coach.

1998 Winter Olympics – Nagano, Japan[edit]

- At the 1998 Winter Olympics in Nagano, Japan, a judge in the ice dancing event tape-recorded another judge trying to pre-ordain the results. Dick Pound, a prominent IOC official, said soon afterward that ice dancing should be stripped of its status as an Olympic event unless it could clean up the perception that its judging is corrupt.[130]

- Canadian gold medalist snowboarder Ross Rebagliati was disqualified for marijuana being found in his system. The IOC reinstated the medal days later.

2002 Winter Olympics – Salt Lake City, Utah, United States[edit]

- Two sets of gold medals were awarded in pairs figure skating, to Canadian pair Jamie Salé and David Pelletier and to Russian pair Elena Berezhnaya and Anton Sikharulidze, after allegations of collusion among judges in favour of the Russian pair.

- Three cross-country skiers, Spaniard Johann Mühlegg and Russians Larissa Lazutina and Olga Danilova, were disqualified after blood tests indicated the use of darbepoetin. Following a December 2003 ruling by the Court of Arbitration for Sport (CAS), the IOC withdrew all the doped athletes’ medals from the Games, amending the result lists accordingly.

2006 Winter Olympics – Turin, Italy[edit]

- Members of the Austrian biathlon team had their Olympic Village residences raided by Italian authorities, who were investigating doping charges.

- Russian biathlete Olga Medvedtseva was stripped of her silver medal won in the individual race, due to positive drug test. A two-year ban from any competition was imposed.

2010 Winter Olympics – Vancouver, Canada[edit]

2014 Winter Olympics – Sochi, Russia[edit]

- In August 2008, the government of Georgia called for a boycott of the Games in response to Russia’s participation in the 2008 South Ossetia war.[131] The IOC responded to concerns about the status of the 2014 games by stating that it was «premature to make judgments about how events happening today might sit with an event taking place six years from now.»[132]

- In mid-2013, a number of organizations, including Human Rights Watch,[133] began calling for a boycott of the Games due to oppressive and homophobic legislation that bans ‘gay propaganda’,[134] including the open acknowledgement of gay identities, the display of rainbow flags and public displays of affection between same-sex couples.[135]

- Severe cost overruns made the 2014 Winter Olympics the most expensive Olympics in history, with allegations of corruption among government officials,[136] and of close relationships between the government and construction firms.[137] While originally budgeted at US$12 billion, various factors caused the budget to expand to US$51 billion, surpassing the estimated $44 billion cost of the 2008 Summer Olympics in Beijing.

- Lebanese skier Jackie Chamoun, who had a photo shoot taken of her wearing nothing but ski boots and a thong, had the Lebanese government claim that she damaged the reputation of her country.[138]

- Doping in Russia — Richard McLaren published two reports in 2016 claiming that from «at least late 2011 to 2015» more than 1,000 Russian competitors in various sports, including summer, winter, and Paralympic sports, benefited from a doping cover-up.[139] As of 25 December 2015, 43 Russian athletes who competed in Sochi have been disqualified, with 13 medals removed.

2018 Winter Olympics – PyeongChang, Republic of Korea[edit]

- Russia was banned by the IOC from attending the Games due to state-sponsored doping.[140] Their athletes participated as the Olympic Athletes from Russia.

- Kei Saito, a Japanese Short Track Speed Skater was suspended after being caught doping.[141]

2022 Winter Olympics – Beijing, China[edit]

- Despite having more cities interested in this Olympics, the bidding process experienced the most dramatic bids withdrawals ever seen. This means when candidate stage was reached, Oslo, Norway should have been chosen as the host location. However, Oslo withdrew the bid later on, effectively making the situation similar to what happened for 1976 Winter Olympics when Denver rejected the games after being awarded. But the difference is, instead of reopening the bidding process, the process continued with the two remaining candidates (Almaty and Beijing).[citation needed]

- Lithuania, Canada, Australia, the United Kingdom, and the United States applied diplomatic boycotts to the Games due to the Uighur Genocide and human rights in Tibet.[142][143][144]

- Japanese government delegates did not attend the Olympics but still sent their team to compete.[145][146]

See also[edit]

- List of stripped Olympic medals

- Campaign for a Scottish Olympic Team

- Doping at the Olympic Games

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g h «Politics no stranger to Olympic Games». The Montreal Gazette. 9 May 1984.

- ^ «Archived copy» (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 March 2012. Retrieved 29 January 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) History Talk - ^ a b «International Olympic Committee – Athletes». Retrieved 16 August 2008.

- ^ «AbeBooks: Crisis at the Olympics». Archived from the original on 13 February 2021. Retrieved 16 August 2008.

- ^ Guttmann, Allen (1992). The Olympics: A History of the Modern Games. Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press. pp. 38. ISBN 0-252-01701-3.

- ^ Newman, Saul (8 August 2018). «Why Grandpa boycotted the Olympics». Haaretz. Archived from the original on 6 December 2018. Retrieved 9 August 2008.

- ^ a b «The Movement to Boycott the Berlin Olympics of 1936». Holocaust Encyclopedia. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. June 2013. Archived from the original on 2 February 2014. Retrieved 8 February 2014.

- ^ «Gov. Earl Urges U.S. Olympic Ban. He Says Here Nazis Will ‘Sell’ Their Philosophy to All Who Attend the Games». New York Times. 4 December 1935. Retrieved 8 February 2014.

Governor George H. Earle of Pennsylvania and Mayor La Guardia joined last night with Alfred J. Lill, member of the American Olympic Committee; Eric Seelig, former amateur light-heavyweight boxing champion of Germany, and others, in urging American withdrawal from the Olympic Games in Berlin next year.

- ^ «Nazification of Sport». The Nazi Olympics Berlin 1936 (Online Exhibition). United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Retrieved 8 February 2014.

- ^ Guttmann, Allen (1984). The games must go on : Avery Brundage and the Olympic Movement. New York: Columbia University Press. pp. 69–70. ISBN 978-0-231-05444-7.

- ^ Paul Taylor (2004). Jews and the Olympic Games: the clash between sport and politics: with a complete review of Jewish Olympic medalists. Sussex Academic Press. ISBN 1-903900-88-3. Retrieved 8 February 2014.

- ^ Hipsh, Rami (25 November 2009). «German film helps Jewish athlete right historical wrong». Haaretz. Retrieved 8 February 2014.

- ^ Sandomir, Richard (7 July 2004). «‘Hitler’s Pawn’ on HBO: An Olympic Betrayal». New York Times. Retrieved 8 February 2014.

- ^ Lehrer, Steven (2006). The Reich Chancellery and Führerbunker complex : an illustrated history of the seat of the Nazi regime. Jefferson, N.C. [u.a.]: McFarland & Co. pp. 47–48. ISBN 9780786423934.

- ^ Hyde Flippo, The 1936 Berlin Olympics: Hitler and Jesse Owens, German Myth 10, german.about.com

- ^ Rick Shenkman, Adolf Hitler, Jesse Owens and the Olympics Myth of 1936 13 February 2002 from History News Network (article excerpted from Rick Shenkman’s Legends, Lies and Cherished Myths of American History, William Morrow & Co, 1988 ISBN 0-688-06580-5)

- ^ «Owens Arrives With Kind Words For All Officials». The Pittsburgh Press. 24 August 1936. Retrieved 8 February 2014.

- ^ Schaap, Jeremy (2007). Triumph: The Untold Story of Jesse Owens and Hitler’s Olympics. New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. ISBN 978-0-618-68822-7.

- ^ O’Sullivan, Patrick T. (Spring 1998). «Ireland & the Olympic Games». History Ireland. Dublin. 6 (1).

- ^ Relman Morin (14 July 1938). «Japan Abandons Olympics Because of War». The Evening Independent. p. 6. Retrieved 29 September 2009.

- ^ «Cold War violence erupts at Melbourne Olympics». Sydney Morning Herald. 7 December 1956. Retrieved 10 August 2008.

- ^ Miles Corwin (1 August 2008). «Blood in the Water at the 1956 Olympics». Smithsonian.com. Retrieved 10 August 2008.

- ^ «SI Flashback». CNN. Retrieved 18 August 2008.

- ^ Benjamin, Daniel (27 July 1992). «Traditions Pro Vs. Amateur». Time. Archived from the original on 2 September 2009. Retrieved 18 March 2009.

- ^ Schantz, Otto. «The Olympic Ideal and the Winter Games Attitudes Towards the Olympic Winter Games in Olympic Discourses—from Coubertin to Samaranch» (PDF). Comité International Pierre De Coubertin. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 May 2013. Retrieved 13 September 2008.

- ^ «1972: Rhodesia out of Olympics». BBC News. 22 August 1972.

- ^ Gary Smith (15 June 1992). «Pieces of Silver». Sports Illustrated. Retrieved 27 August 2010.

- ^ «washingtonpost.com poll». Washingtonpost.com. Retrieved 26 August 2017.

- ^ http://newsblogs.chicagotribune.com/sports_globetrotting/2008/10/marathon-men-th.htm[dead link]

- ^ «The Montreal Olympics boycott | NZHistory.net.nz, New Zealand history online». Nzhistory.net.nz. Retrieved 27 February 2009.

- ^ «BBC ON THIS DAY | 17 | 1976: African countries boycott Olympics». News.bbc.co.uk. 17 July 1976. Retrieved 27 February 2009.

- ^ «Sport: A Matter of Race». Time.com. 19 July 1976. Archived from the original on 6 November 2012. Retrieved 26 August 2017 – via www.time.com.

- ^ «1976 Montréal Summer Games». Olympics at Sports-Reference.com. Archived from the original on 17 April 2020. Retrieved 19 May 2016.

- ^ «BBC – h2g2 – A Guide To Olympic Sports – Fencing». 17 November 2006. Retrieved 16 August 2008.

- ^ CBC News (19 December 2006). «Quebec’s Big Owe stadium debt is over». Cbc.ca. Retrieved 27 February 2009.

- ^ Golan, Galia; Soviet Policies in the Middle East: From World War Two to Gorbachev; p. 193 ISBN 9780521358590

- ^ «Doping violations at the Olympics». The Economist. Retrieved 6 June 2017.

- ^ Wilson, Wayne (PhD); Derse, Ed (2001). Doping in Élite Sport: The Politics of Drugs in the Olympic Movement. Human Kinetics. pp. 77–. ISBN 978-0-7360-0329-2. Retrieved 19 July 2012.

- ^ Sytkowski, Arthur J. (May 2006). Erythropoietin: Blood, Brain and Beyond. John Wiley & Sons. p. 187. ISBN 978-3-527-60543-9.

- ^ «Kozakiewicz Sets World Pole Vault Record». Star-Banner. Ocala, Florida. 31 July 1980.

- ^ Barukh Ḥazan (January 1982). Olympic Sports and Propaganda Games: Moscow 1980. p. 183. ISBN 9781412829953. Retrieved 26 August 2017.

- ^ Jesse Reed. «Top 10 Scandals in Summer Olympic History». Bleacher Report. Retrieved 19 May 2016.

- ^ «Style, Love, Home, Horoscopes & more — MSN Lifestyle». Living.msn.com. Archived from the original on 29 January 2013. Retrieved 19 May 2016.

- ^ «Polanik English». Archived from the original on 31 January 2013. Retrieved 9 August 2012.

- ^ «Soviet pullout rocks Games». The Montreal Gazette. 9 May 1984.

- ^ Litsky, Frank (29 July 1984). «President and Pomp Begin Games». The New York Times. p. 1, 8, § 5. Retrieved 28 August 2020.

Of the first 139 nations in the parade, the biggest cheers went to Rumania, the only Warsaw Pact nation competing here.

- ^ Yake, D. Byron (29 July 1984). «’84 Olympics: Gala trumpets in Games». Beaver County Times. AP. p. A1, A10. Retrieved 28 August 2020.

The Romanians, the only Eastern bloc nation to defy the Soviet boycott, were greeted with a standing ovation.

- ^ «Iran Announces Boycott of the 1984 Olympics». The New York Times. 2 August 1983.

- ^ Ronen, Yehudit; ‘Libya (Al-Jamhāhīriyaa al-‘Arabiyya al-Lībiyya ash-Sha‘biyya al-Ishtirākiyya)’; Middle East Contemporary Survey, Vol. 8, (1983-84); p. 595

- ^ Philip D’Agati, The Cold War and the 1984 Olympic Games: A Soviet-American Surrogate War (2013), p. 132: «Libya also boycotted the Los Angeles Games, but its reason for doing so was caused by the state of Libyan-US relations in 1984 rather than by any political alignment with the Soviet Union».

- ^ Alfano, Peter (11 August 1984). «Boxing; U.S. Protest of Holyfield Loss is Denied». The New York Times.

- ^ John E. Findling; Kimberly D. Pelle (1996). Historical Dictionary of the Modern Olympic Movement. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 182–. ISBN 978-0-313-28477-9.

- ^ Janofsky, Michael (16 January 1988). «CUBANS TURN THEIR BACK ON THE SEOUL OLYMPICS». New York Times. Retrieved 27 September 2017.

- ^ «Seoul Olympics 1988». Retrieved 27 September 2017.

- ^ «Ben Johnson: Drug cheat».

- ^ «A Sad Day in Seoul».

- ^ «The Daily Beast». The Daily Beast. Retrieved 19 May 2016.

- ^ «The week in review: Sport». The Independent. 31 July 1992. Retrieved 5 March 2022.

- ^ Drozdiak, William (31 July 1992). «THREE OLYMPIANS FAIL DRUG TESTS BRITISH TEAM SUSPENDS SPRINTER, WEIGHTLIFTERS». Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 5 March 2022.

- ^ Magotra, Ashish (3 October 2014). «You can keep your medal: Sarita Devi is not alone, others have said ‘no’ too». FirstPost. Retrieved 16 January 2015.

- ^ a b Buchalter, Bill (5 August 1992). «Moroccan Regains His Gold». Orlando Sentinel. Chicago Tribune. Retrieved 27 February 2018.

- ^ Rowbottam, Mike (4 August 1992). «OLYMPICS / Barcelona 1992: Athletics: Kenyan outcry over Skah’s reinstatement». The Independent. Retrieved 27 February 2018.

- ^ «THROWBACK: When a «robbery in Atlanta» denied Onyok Velasco an Olympic Gold». Sports.abs-cbn.com. Retrieved 21 August 2016.

- ^ «Boxing at the 1996 Atlanta Summer Games: Men’s Light-Flyweight». Sports-reference.com. Archived from the original on 18 April 2020. Retrieved 21 August 2016.

- ^ «Boxing’s Big Need: Spray or Roll-On». The New York Times. 4 August 1996. Retrieved 21 August 2016.

- ^ a b «IOC strips Jones of all 5 Olympic medals». MSNBC.com. Associated Press. 12 December 2007. Archived from the original on 18 February 2008. Retrieved 7 July 2010.

- ^ Schmidt, Michael S.; Zinser, Lynn (5 October 2007). «Jones Pleads Guilty to Lying About Drugs». New York Times. Retrieved 5 October 2007.

- ^ As of 2006 Archived 19 August 2008 at the Wayback Machine, pseudoephedrine was not considered a prohibited substance by the World Anti-Doping Agency. The drug was removed from the prohibited list in 2003 Archived 20 November 2008 at the Wayback Machine; the WADA moved the substance to the Monitoring List to assess in-competition use and abuse.

- ^ Wilson, Stephen «IOC strips China of gymnastics bronze «, Sydney Morning Herald, 29 April 2010. Retrieved 29 April 2010

- ^ Emma John (7 August 2012). «London 2012: Gymnastic gold for true flying Dutchman Epke Zonderland». Guardian. Retrieved 9 August 2012.

- ^ «CAS Arbitral Award: Yang Tae-Young v. FIG» (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 September 2007. Retrieved 18 August 2019.

- ^ «Was there ANOTHER MISTAKE MADE in the 2004 men’s Olympic all-around??? -«. 22 January 2010.

- ^ «Vanderlei Cordeiro de Lima é homenageado por medalha de Atenas». Brasil 2016.

- ^ «IFC: Ref made six errors in favor of Italy». ESPN. 22 August 2004. Retrieved 5 July 2012.

- ^ a b c d e Sjöberg, Daniel (14 August 2008). «Pelle Svensson: Jag blev mordhotad». Aftonbladet (in Swedish). Retrieved 17 August 2008.

- ^ «Spanish Olympic basketball team in ‘racist’ photo row – CNN.com». 14 August 2008. Retrieved 16 August 2008.

- ^ «Daily Times – Leading news resource of Pakistan – Abrahamian faces rap for binning bronze». Retrieved 16 August 2008.

- ^ Pucin, Diane (28 July 2008). «Issues raised about Chinese athletes’ ages». Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 16 August 2008.

- ^ «Handball-S.Korea’s appeal against Norway win rejected – Olympics – Yahoo! Sports». Retrieved 24 August 2008.

- ^ «Cuban banned for referee kick – Reuters». 23 August 2008. Retrieved 24 August 2008.

- ^ «Cuban kicks ref». Herald Sun. Retrieved 24 August 2008.

- ^ David Barboza (5 August 2008). «Chinese gymnast endured childhood sacrifice». International Herald Tribune.

- ^ Howard W. French (20 June 2008). «In Quest for Gold and Glory at Olympics, China Pressures Injured Athletes». The New York Times.

- ^ «London 2012: North Koreans walk off after flag row». BBC News. 25 July 2012. Retrieved 31 July 2012.

- ^ «Greek triple jumper Paraskevi Papachristou withdrawn from Olympics following racist tweet about African immigrants». Independent. London. 25 July 2012. Retrieved 25 July 2012.

- ^ «Greek athlete suspended from Olympic team for offensive remarks». CNN. 26 July 2012. Retrieved 26 July 2012.

- ^ «Fencing Controversy Causes South Korea’s Shin A Lam To Protest on Piste». Retrieved 31 July 2012.

- ^ «Olympics fencing: Tearful Shin A Lam denied chance at gold». Archived from the original on 30 July 2012. Retrieved 31 July 2012.

- ^ «Olympic gymnastics: Why does bronze mean so much for Britain?». Retrieved 31 July 2012.

- ^ «SaltWire | Halifax».

- ^ «Controversy mars Americans’ 4–3 win over Canada, but shouldn’t detract from a great game». Yahoo! Sports. 7 August 2012. Retrieved 7 August 2012.

- ^ «London 2012 soccer: Controversial call against Canada in U.S. semifinal rarely made». Toronto Star. 7 August 2012.

- ^ «FIFA to probe Canadian remarks». Japan Times. Associated Press. 9 August 2012. p. 17.

- ^ «Christine Sinclair’s suspension wasn’t for comments to media». CBC News.

- ^ Kelly, Cathal (12 June 2015). «The greatest game of women’s soccer ever played». The Globe and Mail.

- ^ «Olympics badminton: Eight women disqualified from doubles». BBC Sport. 1 August 2012.

- ^ «Olympic boxing: referee sent home after Satoshi Shimizu wins appeal». The Guardian.

- ^ «Controversial Win For Japan Over Thailand in Olympic Qualifier». Flovolleyball.tv. Retrieved 21 August 2016.

- ^ Thailand, Nation Multimedia Group Public Company Limited, Nationmultimedia.com. «Thailand go down to Japan in close battle amidst controversial referee’s decision — The Nation». Nationmultimedia.com. Retrieved 21 August 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ «Volleyball drama: FIVB refuses to evaluate judge who gave Thailand red cards». Bangkok.coconuts.co. 25 May 2016. Retrieved 21 August 2016.

- ^ «Olympics ethics committee warns Egyptian judoka Shehabi — Egypt Independent». Egyptindependent.com. 15 August 2016. Retrieved 26 August 2017.

- ^ «Polícia Federal retira nadadores americanos de avião para os EUA». M.oglobo.globo.com. 17 August 2016. Retrieved 21 August 2016.

- ^ «Article expired». The Japan Times. 10 May 2013. Retrieved 26 August 2017.

- ^ Temp Weightlifting Men’s +105 kg Results Archived 20 September 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ «Iran files application to CAS on Salimi’s case». Mehr News Agency. 17 August 2016. Retrieved 26 August 2017.

- ^ Kulkarni, Manali. «CAS Rio: The CAS ad hoc division in Rio closes with a total of 28 procedures registered». Lawinsport.com. Retrieved 26 August 2017.

- ^ «CAS OG 16/28 Behdad Salimi & NOCIRI v. IWF» (PDF). Tas-cas.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 February 2017. Retrieved 26 August 2017.

- ^ «Dez atletas australianos são detidos após tentativa de adulterar credenciais». Folha de São Paulo. 20 August 2016. Retrieved 21 August 2016.

- ^ «Wrestling — Men’s Freestyle 65 kg — Match Number 398 — Mat B» (PDF). Rio 2016. 21 August 2016. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 September 2016. Retrieved 22 August 2016.

- ^ «Mongolian wrestling coaches go nuts, strip down after unfavorable decision». Usatoday.com. Retrieved 26 August 2017.

- ^ «Olympic coaches strip in front of everyone». News.com.au. 21 August 2016. Retrieved 26 August 2017.

- ^ a b «Rio Olympics 2016: Boxing judges are ‘crazy’ over new scoring system». BBC Sport. BBC. 16 August 2016.

- ^ «Olympic heavyweight final booed at Rio 2016». Boxing News. 16 August 2016.

- ^ «Michael Conlan calls out Vladimir Putin in first tweet since controversial loss». SportsJOE.ie.

- ^ «Number of Olympic boxing judges dropped from duty». ITV. 17 August 2016.

- ^ «Olympic Boxing: Judges sent home amid criticism». SkySports. 17 August 2016.

- ^ «CAS AD 16/10 and 16/11. The Anti-doping Division of the Court of Arbitration for Sport Issues Decisions in the Cases of Gabriel Sincrain (ROM/Weightlifting-85kg) and Misha Aloian (RUS/Boxing-52kg)» (PDF). Court of Arbitration for Sport. 8 December 2016. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 December 2016. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- ^ «Joint Statement from the International Olympic Committee and the Tokyo 2020 Organising Committee». olympic.org (press release). IOC. 24 March 2020. Archived from the original on 19 April 2020. Retrieved 26 January 2021.

- ^ «Algerian judoka sent home from Olympics after refusing to face Israeli». TheGuardian.com. 24 July 2021.

- ^ «Algerian judoka Fethi Nourine suspended and sent home for withdrawing to avoid Israeli». 24 July 2021.

- ^ «Algerian judoka & coach get 10-year ban». BBC Sport.

- ^ «DECISION OF THE DISCIPLINARY COMMISSION OF THE GYMNASTICS ETHICS FOUNDATION» (PDF).

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Horvitz, Peter S. (2007). The Big Book of Jewish Sports Heroes: An Illustrated Compendium of Sports History and The 150 Greatest Jewish Sports Stars. ISBN 9781561719075. Retrieved 27 February 2011.

- ^ Siegman, Joseph M. (15 September 1906). The International Jewish Sports Hall … ISBN 9781561710287. Retrieved 27 February 2011.

- ^ www.Olympic.org IOC, 1968 Grenoble Games.

- ^ Jenkins, Dan (26 February 1968). «JEAN-CLAUDE WINS THE BATTLE AND THE WAR». Sports Illustrated. No. 26 Feb. 1968. Retrieved 13 February 2018.

- ^ «They Said It — 02.14.72 — SI Vault». Archived from the original on 9 June 2009. Retrieved 16 August 2008.

- ^ «When Denver rejected the Olympics in favour of the environment and economics». The Guardian. 7 April 2015. Archived from the original on 21 June 2023.

- ^ Kiat.net Archived 17 June 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ «Ice Dancers Struggle To Prove Legitimacy». The New York Times. 15 February 2002. Retrieved 19 May 2016.

- ^ Weir, Fred (11 July 2008). «Putin Faces Green Olympic Challenge». Christian Science Monitor. Archived from the original on 22 August 2009. Retrieved 18 August 2008.

- ^ Hefling, Kimberly (15 August 2008). «Lawmakers want Olympics out of Russia». USA Today. Associated Press.

- ^ «Human Rights Watch». Human Rights Watch. Retrieved 26 August 2017.

- ^ Elder, Miriam. (11 June 2013). Russia passes law banning gay ‘propaganda’. Law will make it illegal to equate straight and gay relationships and to distribute gay rights material. The Guardian, UK.

- ^ Johnson, Mark. (4 July 2013). Sochi 2014 Olympics Unsafe For LGBT Community Under Russia’s Anti-Gay Law, Activists Warn. International Business Times.

- ^ Bennetts, Marc (19 January 2014). «Winter Olympics 2014: Sochi Games «nothing but a monstrous scam,» says Kremlin critic Boris Nemtsov». Telegraph. London. Retrieved 4 February 2014.

- ^ «The Sochi Olympics: Castles in the sand». The Economist. 13 July 2013. Retrieved 8 August 2013.

- ^ «Lebanese Olympic Skier Jackie Chamoun Topless Photos Cause Scandal». TIME.com. Archived from the original on 12 February 2014. Retrieved 19 May 2016.

- ^ Ruiz, Rebecca R. (9 December 2016). «Russia’s Doping Program Laid Bare by Extensive Evidence in Report». The New York Times.

- ^ Ruiz, Rebecca R. (5 December 2017). «Russia Banned From Winter Olympics by I.O.C.» The New York Times.

- ^ Zayn Nabbi; Jo Shelley. «Japanese speed skater Kei Saito suspended from Winter Olympics for doping». CNN. Retrieved 22 February 2018.

- ^ «Lithuania confirms diplomatic boycott of Beijing 2022 Winter Olympics». ANI News. Retrieved 30 December 2021.

- ^ Ben Westcott and Caitlin McGee (8 December 2021). «Australia, UK and Canada join diplomatic boycott of Beijing 2022 Winter Olympics». CNN. Retrieved 30 December 2021.

- ^ «Why are countries boycotting the Beijing Olympics? Here’s what you need to know — National | Globalnews.ca». Global News. Retrieved 30 December 2021.

- ^ «Japan PM will not attend Beijing Winter Olympics opening ceremony». the Guardian. 16 December 2021. Retrieved 30 December 2021.

- ^ «Japan to quietly snub Beijing Olympics, but won’t call it a boycott». Nikkei Asia. Retrieved 30 December 2021.

External links[edit]

- Moran, Michael; Bajoria, Jayshree; et al. «Politics and the Olympics». Council on Foreign Relations. Archived from the original on 19 April 2010. Retrieved 22 June 2010.

Первое и зачастую самое яркое событие всех Олимпийских игр — их церемония открытия. Ни один главный старт четырёхлетия не может обойтись без этой, порой формальной, но красивой процедуры. Каждый раз организаторы хотят удивить весь мир каким-то шоу, которое часто не обходится без запоминающихся ляпов и косяков.

1956 год: первый прямой эфир и первый ляп

Середина XX века — время прогресса телевидения. Зрители получили возможность смотреть самые разные события в прямом эфире. Одним из таких стали зимние Игры в итальянском городе Кортина-д’ Ампеццо. Технический прогресс в те годы не позволял обойтись без множества проводов, они-то и сыграли свою роль.

Конькобежец Гвидо Кароли нёс в руках олимпийский огонь, однако сделать это без курьёзов ему помешал телевизионный кабель, об который он и споткнулся. В итоге огонь погас — и его пришлось зажигать заново. Благо после этого никаких трудностей не было.

Сеул-1988: горящие голуби

Картина куда более жуткая произошла через 32 года в корейском Сеуле. К слову, Игры в Корее стали последними, где на церемонии открытия организаторы использовали живых голубей. Символ мира и единства олимпийской семьи был запущен, казалось, в небеса, однако на деле всё оказалось куда печальнее.

Когда факелоносцы зажигали олимпийский огонь, на край специальной чаши сели белые голуби. Разумеется, через несколько мгновений огонь загорелся, а вот что стало с голубями — можете догадаться сами.

Ванкувер-2010: не поднявшийся жёлоб

Ещё один ляп, который увидел весь мир, случился в канадском Ванкувере на открытии Игр 2010 года. Эпоха высоких технологий начала брать своё, и даже для зажигания олимпийского огня начали использовать самые разные приспособления.

Зажечь огонь должны были сразу четыре человека. Однако сначала целых десять минут просто ничего не происходило, а затем на арене поднялись большие желоба. Но не четыре, а три. В итоге конькобежка Катриона Лемэй-Доан была вынуждена некоторое время просто стоять и делать вид, что всё идёт по плану. Впрочем, довольные зрители на арене ничего особо не заметили и обрадовались началу Игр.

Кстати, поднять четвёртый жёлоб удалось уже после церемонии открытия. Честь и хвала канадским организаторам, которые решили обратить внимание на такой ляп уже на церемонии закрытия Игр. Получилось достаточно весело, да и зрители по всему миру это оценили.

Сочи-2014: а где пятое кольцо?

Первая для России зимняя Олимпиада в истории проходила в самом, на первый взгляд, неподходящем для этого месте — в Сочи. Южный курорт сумел великолепно принять Игры, которые до сих пор многие называют лучшими. Да и шоу на двух церемониях — открытия и закрытия — получилось более чем грандиозным.

Первое мероприятие Игр запомнилось всем не шикарной темой, не показом всех граней русской культуры и истории, а достаточно забавным ляпом. По сценарию, пять снежинок должны были превратиться в олимпийские кольца. Четыре из них это сделали, а вот пятая не смогла. Впрочем, зрители в нашей стране этого ляпа не увидели.

— Я потом расследовал: ирландские риггеры (специалисты по обслуживанию парашютной техники), которые их делали, ночью уронили одно кольцо, и, видя меня, который не спал пятые сутки, они побоялись об этом сказать. Когда мы увидели, что кольцо не раскроется, приняли решение запустить видео с репетиции. Но это был единственный момент, когда пришлось к этому прибегнуть. Для нас это не стало трагедией, — заявил главный продюсер церемонии Константин Эрнст.