В самом начале должны открыть правду — в медицине НИЧЕГО не бывает на 100%. Априори ни один метод диагностики и скрининга патологий плода не превышает точность 99.9999% Потому что медицина, генетика, биология, биоинформатика и прочие науки постоянно развиваются, всегда появляются новые теории и методы, что оставляет ученым всегда право на ошибку. В структуре хромосомной патологии человека 45% случаев относятся к анеуплоидиям половых хромосом, а 25% приходится на группу аутосомных трисомий, самыми частыми из которых являются трисомии по хромосомам 21, 18, 13 [1].

Клиническая картина хромосомных патологий:

- врожденные пороки развития,

- малые аномальные развития,

- умственная отсталость;

- неврологическая,

- психиатрическая,

- гематологическая патология,

- нарушения слуха,

- зрения.

Хромосомные аномалии одна из самых актуальных проблем здравоохранения, по данным ВОЗ:

- 0,8% всех новорождённых,

- 40% новорожденных с множественными пороками развития,

- 15% детей с умственной отсталостью,

- 7% случаев мертворождений,

- ХА причина 70% случаев инвалидности у детей,

- нет лечения социальная дезадаптация

По состоянию на 2021 год в России применяется несколько методов определения генетических патологий плода:

Ранний пренатальный скрининг

Инвазивная диагностика

Неинвазивное пренатальное тестирование

Ранний пренатальный скрининг

Или по другому комбинированный скрининг I триместра. В России широкое применение РПС по международному стандарту было инициировано Минздравсоцразвития России только в 2009 г. с поэтапным внедрением нового алгоритма диагностики хромосомных патологий плода в субъектах страны в период с 2010 по 2014 [1].

Данный вид диагностики был разработан фондом медицины плода (FMF) и подразумевает под собой проведение ультразвукового исследования и анализа сывороточных маркеров материнской крови (бетта-ХГЧ и PAPP-A). Расчет риска, с учетом индивидуальных особенностей беременной (возраст матери и срок беременности) происходит с помощью унифицированной программы “Astraia” (Астрайя).

Каждая беременная женщина, которая встает на учет знает, что данный вид скрининга предстоит ей в период с 11 до 14 недель. По результатам скрининга женщина может получить как низкий риск рождения ребенка с патологией, так и высокий (граница 1:100).

Какова же точность скрининга I триместра, который проводят каждой беременной женщине в России:

![Данные: Анализ результатов раннего пренатального скрининга в Российской Федерации АУДИТ – 2019. Информационно-справочные материалы. Письмо МЗРФ № 15-4/2963-07 от 11.10.2019 [2]](https://msk.medicalgenomics.ru/assets/components/directresize/cache/dr_unnamed%20(2)_w400_h266.png)

Стоит отметить что 20% детей рожденных с синдромом Дауна (с трисомией 21) были рождены в группе низкого риска. [3]

Также сравнительный анализ показал, что комбинированный скрининг эффективнее исследования только биохимических или ультразвуковых маркеров (87% вместо 71%) [4].

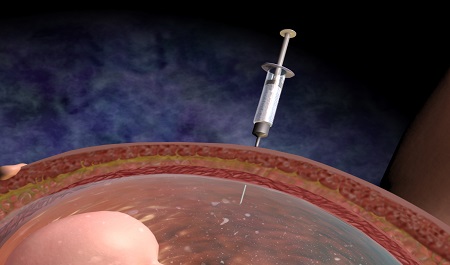

Инвазивная пренатальная диагностика

Данный вид диагностики включает в себя процедуру забора разного вида биоматериала (в зависимости от срока беременности) из полости матки с помощью пункции под контролем УЗИ. Среди беременных процедуру часто называют “прокол”, длительность процедуры (подготовки и самой пункции) от 5 до 7 минут.

У инвазивной пренатальной диагностики есть свои ограничения и риски осложнений [5]:

- Самопроизвольное прерывание беременности (выкидыш): после амниоцентеза — 0,81%; после биопсии ворсин хориона – 2,18%

- Внутриутробное инфицирование 0,001%

- У носителей хронических вирусных гепатитов, ВИЧ-инфекции, при острых инфекционных процессах – риск высокий.

- Наличие абсолютных противопоказаний к процедуре: истмико-цервикальная недостаточность, угроза прерывания (наличие кровотечения)

- Избыток подкожно-жировой клетчатки, возможные технические трудности при проведении процедуры

- Беременной с резус-отрицательным фактором необходим контроль уровня антител перед процедурой, при их отсутствии — введение антирезусного иммуноглобулина после процедуры.

По данным FMF риски < 1% — 1: 100 Т.е. у каждой 100 женщины, после процедуры случился выкидыш.

Несмотря на ограничения, противопоказания и возможные риски инвазивная пренатальная диагностика является признанным методом в России. В случае выявления высокого риска хромосомных аномалий, пациентке рекомендуется проведение инвазивного обследования (плацентоцентез, амниоцентез, кордоцентез) [6].

Точность инвазивной диагностики свыше 99%.

Однако есть ограничение метода, связанное с редким явлением плацентарного мозаицизма: в 1-2% биопсии ворсин хориона (плацентозентезе) [5]. Это два или более клона клеток с разным хромосомным набором. Может быть ложный результат диагностики или выявление мозаицизма. При этом мозаицизм у плода выявляется в 30-40% случаев.

При амниоцентезе может быть ложный результат в случае тканевого мозаицизма у плода. В амниотической жидкости представлены не все клеточные линии плода: только клетки кожи, ЖКТ, мочевого пузыря и легких.

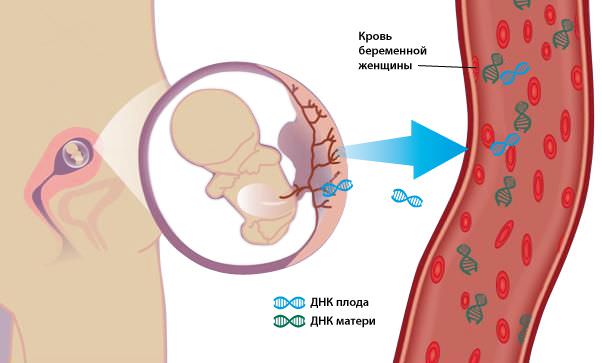

Неинвазивная пренатальная диагностика

Неинвазивный пренатальный тест (НИПТ) — это скрининговый метод. Сегодня в России проводят около 30-40 тысяч НИПТ в год, всего НИПТ сделали от 4 до 6 млн женщин (по состоянию на 2017 год) [1].

Само исследование представляет собой технологически сложный и затратный по времени процесс, включающий такие этапы как:

- взятие образца крови у пациента и получение плазмы,

- выделение ДНК и пробоподготовка,

- секвенирование,

- биоинформатические анализ,

- подготовка заключения.

Точность НИПТ

Во всех метаанализах сделан вывод, что НИПТ с помощью анализа внеклеточной ДНК плода в материнской плазме является высокоэффективным методом скрининга частых хромосомных аномалий — трисомии 21,18 и 13 [8-11] как при одноплодной беременности, так и для близнецов.

В связи с низким процентом ложноположительных результатов специфичность НИПТ в подавляющем большинстве публикаций была высокой и колебалась в пределах 98-99,9%.

Авторы исследований отмечают, что скрининг на трисомию 21 (синдром Дауна) с помощью анализа фетальной внеклеточной ДНК в материнской крови превосходит все другие традиционные методы скрининга с более высокой чувствительностью и более низким процентом ложноположительных результатов [8].

Доля ложноположительных результатов исследований по пяти хромосомам оценивается от 0,1 до 0,9% [7].

У данного метода тоже есть ограничения и противопоказания:

- Синдром исчезающего близнеца

- Хромосомные аномалии или хромосомный мозаицизм у матери

- Не проводится ранее 10-ти недель беременности

- Для беременностей двойней не проводится тест на анеуплоидии половых хромосом

- Не проводится для беременности тройней и большим количеством плодов

- Не предназначен и клинически не подтвержден для определения мозаицизма, частичной трисомии или транслокаций, а также для выявления хромосомной патологии по незаявленным хромосомам

- Опухоли у женщины на данный момент или в прошлом, трансплантация органов или костного мозга, стволовых клеток в прошлом (в этих случаях повышен риск ложного результата тест).

Получить консультацию специалиста

Хотите пройти тест НИПТ?

Оставьте заявку, мы постараемся вам помочь!

Список литературы:

- Современное значение неинвазивного пренатального исследования внеклеточной ДНК плода в крови матери и перспективы его применения в системе массового скрининга беременных в Российской Федерации © Е.А. Калашникова, А.С. Глотов , Е.Н. Андреева, И.Ю. Барков , Г.Ю. Бобровник, Е.В. Дубровина, Л.А. Жученко

- Анализ результатов раннего пренатального скрининга в Российской Федерации АУДИТ – 2019. Информационно-справочные материалы. Письмо МЗРФ № 15-4/2963-07 от 11.10.2019

- Жученко, Л. А., Голошубов, П. А., Андреева, Е. Н., Калашникова, Е. А., Юдина, Е. В., Ижевская, В. Л. (2014). Анализ результатов раннего пренатального скрининга, выполняющегося по национальному приоритетному проекту «Здоровье» в субъектах Российской Федерации. Результаты российского мультицентрового исследования «Аудит-2014». Медицинская генетика, 13(6), 3-54.

- S Kate Alldred, Yemisi Takwoingi, Boliang Guo, Mary Pennant, Jonathan J Deeks, James P Neilson, Zarko Alfirevic First trimester ultrasound tests alone or in combination with first trimester serum tests for Down’s syndrome screening

- Queenan, J. T. et al. (2010). Protocols for high-risk pregnancies: an evidence-based approach. John Wiley & Sons. – 661 p. R. AKOLEKAR, J. BETA, G. PICCIARELLI, C. OGILVIE and F. D’ANTONIO. Procedure-related risk of miscarriage following amniocentesisand chorionic villus sampling: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2015; 45: 16–26.

- Приказ Минздрава России от 20.10.2020 N 1130н «Об утверждении Порядка оказания медицинской помощи по профилю «акушерство и гинекология» (Зарегистрировано в Минюсте России 12.11.2020 N 60869)

- Lui X. Mils. «Financing reforms of public health services in China: Lessons for other nations». Social Science and Medicine, 2002; 54:1691-1698. «Non-invasive prenatal testing for fetal aneuploidy: charting the course from clin- ical validity to clinical utility». Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2013; 41: 2-6.

- Gil MM, Quezada MS, Revello R, et al. Analysis of cell-free DNA in maternal blood in screening for fetal aneuploidies: updated meta-analysis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2015;45:249–266. doi: 10.1002/uog.14791

- Gil MM, Accurti V, Santacruz B, et al. Analysis of cell-free DNA in maternal blood in screening for aneuploidies: updated meta-analysis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2017;50:302–314. doi: 10.1002/uog.17484

- Mackie FL, Hemming K, Allen S, et al. The accuracy of cellfree fetal DNA-based non-invasive prenatal testing in singleton pregnancies: a systematic review and bivariate meta-analysis. BJOG. 2017;124:32–46. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.14050

- Taylor-Phillips S, Freeman K, Geppert J, et al. Accuracy of non-invasive prenatal testing using cell-free DNA for detection of Down, Edwards and Patau syndromes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2016;6(1):e010002. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010002

18.10.201610:5618.10.2016 10:56:47

Появление на свет детей с наследственными заболеваниями и тяжелыми пороками развития – нелегкое испытание для семьи. Статистические данные говорят о том, что не менее 5% детей рождается с теми или иными вариантами наследственных заболеваний.

Ни одна супружеская пара не застрахована от подобного случая. Цель всех исследований, позволяющих выявить заболевания на ранних стадиях – предоставление информации родителям с целью дальнейшего принятия решения о пролонгировании или прерывании беременности.

На этапе планирования беременности к генетику может обратиться любая супружеская пара, это добровольное решение.

Однако существуют ситуации, когда консультация генетика имеет медицинские показания и является обязательной:

- наличие повышенного риска по результатам комбинированных пренатальных скринингов (ультразвуковых и/или биохимических)

- возраст беременной старше 35 лет и младше 18

- рождения ребенка с хромосомной патологией или выявление таковой у плода в предыдущие беременности

- носительство семейной хромосомной аномалии

- перенесение острой вирусной инфекции на ранних сроках беременности (ОРВИ, краснуха, герпес, гепатит, ВИЧ и т.д.)

- прием препаратов, запрещенных при беременности непосредственно в период до зачатия или на ранних сроках, наркттических препаратов

- облучение одного из супругов в период зачатия, воздействие радиации, химических веществ

- кровное родство пары

- беременности с неудачными исходами (привычное невынашивание, антенатальные гибели) или бесплодие неясного генеза

Инвазивные методы диагностики

К видам инвазивной диагностики относятся – биопсия ворсин хориона, амниоцентез, кордоцентез, плацентоцентез, взятие тканей плода. Цель данной методики – получение образца тканей, в ходе исследования которых возможно проведение полноценной достоверной диагностки. Полученный материал возможно исследовать следующими способами:

* цитогенетическим. При этом методе выявляется количественное нарушение в хромосомном наборе (синдром Дауна, Тернера и т.д.)

* молекулярно-генетическим. Этот метод делает возможным выявить нарушения внутри хромосом (муковисцедоз, мышечная дистрофия, фенилкетонурия ит.д.)

* биохимическим

Инвазивная диагностика может быть предложена по высокому пренатальному риску, либо по иным причинам, ставшим поводом для обращения . В каждом конкретном случае оценивается индивидуальный риск и решается вопрос в зависимости от анамнеза и текущей ситуации. Решение принимается непосредственно семейной парой, в задачи врача входит профессионально и корректно донести информацию о необходимости проведения процедуры и степени риска.

Инвазивное диагностическое исследование проводится всегда опытным специалистом, под контролем ультразвука. Доступ возможен через влагалище или переднюю брюшную стенку. В стерильных условиях производится пункция (прокол), далее забор необходимого материала – частиц ворсин хориона, амиотической жидкости или пуповинной крови. Выбор метода диагностики определяет врач в зависимости от срока и показаний.

Биопсия ворсин хориона проводится на сроке 11-12 недель беременности. Если принимается решение о необходимости прерывания беременности, то срок до 12 недель считается наиболее безопасным для женщины. При помощи этого метода возможно провести диагностику синдрома Дауна, Патау, Эдвардса и иных генных мутаций. Риски данного метода заключаются в возникновении выкидыша, кровотечений, инфицирования плода. Также необходимо отметить и возможность диагностической погрешности – исследование ворсин хориона не может не совпасть к геномом эмбриона, что означает возможность получения ложноположительных или ложноторицательных результатов. Безусловно, эти риски очень невелики, не более 2%, однако об этом следует знать.

Амниоцентез – это метод исследования околоплодной жидкости, при котором возможно получить информацию не только о генных и хромосомных нарушениях плода, но и некоторых биохимических показателях. Например, определить наличие резус-конфликта или степень зрелости легких плода. Проведение амниоцентеза возможно с 15-16 недель беременности. Забор жидкости осуществляется путем пункции передней брюшной стенки и последующего проникновения в полость матки. Вероятность осложнений после амниоцентеза не так высока как при биопсии ворсин хориона, однако в некоторой степени сохраняется – это риски подтекания вод, инфицирования, угрозы прерывания беременности.

Кордоцентез – это забор пуповинной крови. Проводится после 20 недели беременности, метод из себя представляет пункцию передней брюшной стенки с дальнейшим получением пуповинной крови под контролем УЗИ. Поскольку исследуется кровь, то это значительно расширяет спектр анализов, кроме генных и хромосомных нарушений возможно исследование всего биохимического спектра. А в некоторых случаях данный метод можно использовать как лечебный – вводить через пуповину лекарственные средства плоду.

Биопсия тканей плода производится для диагностики тяжелых наследственных патологий кожи или мышц плода.

Ненвазивный пренатальный тест

Метод неинвазивной пренатальной ДНК-диагностики — высокотехнологичный, принципиально новый метод диагностики, на сегодняшний день является наиболее достоверным и информативным способом выявления и подтверждения хромосомной патологии плода. В основе метода лежит анализ клеток плода, циркулирующих в крови матери. Внеклеточная фетальная ДНК плода свободно циркулирует в крови матери, легко поддается выделению и обладает высокой диагностической ценностью. Анализ фрагментов ДНК плода позволяет получить данные о наиболее значимых хромосомных синдромах. Важнейшие преимущества метода неинвазивной пренатальной ДНК-диагностики:

· абсолютная безопасность матери и плода

· высокая диагностическая точность. Ложноположительные результаты составляют 0,1%

· возможность получения результатов на самых ранних сроках, начиная с 9 недели.

Помимо скрининга аномалий хромосомного набора, метод неинвазивной диагностики фетального ДНК позволяет выявить синдромов, связанных с микроделециями. Это заболевания, возникающие из-за выпадения маленьких участков хромосом. Развитие подобных патологических ситуаций фактически является «генетической случайностью», не связано с возрастом родителей, семейным анамнезом или воздействием внешних факторов. Микроделеционные синдромы ассоциированы со следующими заболеваниями:

· Синдром делеции 22q11.2 (Синдром Ди Джорджи)

· Синдром делеции 1p36

· Синдром Ангельмана

· Синдром “кошачьего крика”

· Синдром Прадера-Вилли

Современная медицина обладает широкими возможностями выявления тяжелых патологий еще на ранних сроках беременности. Цель медико-генетического консультирования состоит в правильной постановке диагноза, объяснении перспектив развития того или иного заболевания, информировании и методах диагностики и рисках. Именно семейная пара принимает решение о дальнейшей судьбе течения беременности и задача врача – поддержать при принятии любого варианта действий.

Кафедра акушерства и гинекологии стоматологического факультета Московского государственного медико-стоматологического университета им. А.И. Евдокимова (ректор — проф., засл. врач О.О. Янушевич) Минздрава России, ул. Делегатская, д. 20, стр. 1, Москва, 127473

Мачарашвили Т.К.

ГБОУ ВПО

«Московский государственный медико-стоматологический университет им. А.И. Евдокимова» (ректор — проф. О.О. Янушевич) Минздрава России, Москва, Россия, 127473

Причины низкой эффективности пренатальной диагностики генетической патологии плода

Авторы:

Акуленко Л.В., Манухин И.Б., Мачарашвили Т.К.

Как цитировать:

Акуленко Л.В., Манухин И.Б., Мачарашвили Т.К. Причины низкой эффективности пренатальной диагностики генетической патологии плода. Проблемы репродукции.

2015;21(4):114‑120.

Akulenko LV, Manukhin IB, Macharashvili TK. The reasons of low efficiency of prenatal genetic diagnosis. Russian Journal of Human Reproduction. 2015;21(4):114‑120. (In Russ.)

https://doi.org/10.17116/repro2015214114-120

Высокая частота генетически детерминированной патологии у новорожденных (около 7%), весомый вклад генетических факторов в репродуктивные потери (более 40%) и показатели детской смертности (около 50%) определяют профилактику врожденных и наследственных заболеваний как приоритетное направление в здравоохранении всех стран мира [1, 2, 4]. Решающая роль в комплексе мероприятий по профилактике наследственных и врожденных заболеваний принадлежит пренатальной диагностике (ПД) — разделу медицинской генетики, возникшему в 80-х годах XX века на стыке клинических дисциплин (акушерство, гинекология, неонатология) и фундаментальных наук (патофизиология, биохимия, цитогенетика, молекулярная биология, генетика человека) [1, 2].

В России П.Д. регламентирована приказом Министерства здравоохранения № 457 от 28 ноября 2000 г. «О совершенствовании пренатальной диагностики в профилактике наследственных и врожденных заболеваний у детей», который до настоящего времени является основополагающим и предусматривает двухуровневый порядок обследования беременных женщин. Первый уровень заключается в проведении массового скрининга беременных акушерско-гинекологическими учреждениями — женскими консультациями, кабинетами и другими родовспомогательными учреждениями в I и II триместрах беременности на основе использования фетальных биохимических и ультразвуковых маркеров. Второй уровень включает мероприятия по диагностике конкретных форм поражения плода, оценке тяжести болезни и прогнозу состояния здоровья ребенка, а также решение вопросов о прерывании беременности в случаях тяжелого, не поддающегося лечению заболевания плода, которые осуществляются в региональных (межрегиональных) медико-генетических консультациях [11].

С научной точки зрения проблемы, связанные с ПД, в настоящее время уже принципиально решены. В практическом же плане существует ряд нерешенных проблем, связанных с крайне низкой эффективностью дородовых профилактических мероприятий. Сегодня все еще каждый второй порок и многие грубые нарушения развития плода не диагностируются антенатально, что приводит к росту детской заболеваемости, летальности, инвалидности, в том числе и по причине несвоевременной коррекции врожденных аномалий [4—6].

В последние годы в России были предприняты кардинальные преобразования в системе ПД с целью повышения ее эффективности. Так, Министерством здравоохранения и социального развития Российской Федерации в 2009 г. издан приказ № 808н «Об утверждении порядка оказания акушерско-гинекологической помощи», который исключил из алгоритма ПД во II триместре биохимический скрининг и установил более ранние сроки проведения ультразвукового исследования (УЗИ) [12]. В 2010 г. в рамках приоритетного национального проекта «Здоровье» открыт новый раздел: «Пренатальная (дородовая) диагностика нарушений развития ребенка», концепция которого состоит в создании межтерриториальных, окружных, региональных кабинетов и центров ПД, призванных обеспечить каждую беременную женщину возможностью обследования плода на экспертном уровне, что требует наличия подготовленных специалистов и оборудования экспертного класса [8].

Вместе с тем не вызывает сомнений, что главная роль в системе мероприятий по профилактике генетической патологии плода принадлежит врачам первого контакта с беременной женщиной — акушерам-гинекологам. Именно в их компетенции находится выполнение главного условия достижения эффективности ПД — своевременное направление беременных женщин с высокой степенью мотивации обследования и при их полном информированном согласии на всех этапах наблюдения.

С целью поиска путей повышения эффективности ПД врожденных и наследственных заболеваний нами предпринято исследование, направленное на изучение потребности в совершенствовании деятельности амбулаторного звена акушерско-гинекологической службы.

Материал и методы

Исследование выполнено на ретроспективном материале одной из женских консультаций Москвы. Материал исследования представили амбулаторные карты 290 женщин, состоявших на учете по беременности с 2007 по 2011 г. Обследование беременных проводилось согласно приказам, регламентирующим ПД в эти годы [11, 12], включая:

1) трехкратное ультразвуковое исследование (УЗИ): 1) на 10—13-й неделе беременности (оценка копчиково-теменного расстояния — КТР и толщины воротникового пространства плода — ТВП); 2) на 20—23-й неделе беременности (выявление пороков развития и эхографических маркеров хромосомных болезней плода); 3) на 30—33-й неделе беременности (выявление пороков развития с поздним проявлением, функциональная оценка состояния плода);

2) обязательное двукратное исследование уровня не менее двух биохимических маркеров врожденной патологии плода: 1) плазменного протеина-А, связанного с беременностью (PAPP-A), и β-субъединицы хорионического гонадотропина (β-ХГ) на сроке беременности 10—13 нед; 2) α-фетопротеина (АФП) и β-ХГ на сроке беременности 16—20 нед.

Концентрацию β-чХГ и PAPP-A в материнской сыворотке в I триместре и АФП, свободного β-чХГ и E3 во II триместре беременности определяли на анализаторе 6000 DelfiaXpress («Perkin Elmer», Wallac) иммунофлюоресцентным методом с разрешением по времени. Значения сывороточных маркеров считали нормальными, если они находились в пределах от 0,5 до 2,0 МоМ.

УЗИ выполнялось на аппарате Sonix RP, оснащенном всеми типами датчиков, использующимися в акушерских исследованиях. Во всех случаях измеряли КТР и ТВП. Все измерения проводились согласно существующим рекомендациям.

Окончательный расчет риска рождения ребенка с хромосомной патологией производили в лаборатории Московского городского центра неонатального скрининга на базе детской психиатрической больницы № 6 с помощью аппаратно-программного комплекса LifeCycle, основной задачей которого является пренатальный скрининг (ПС) плода на наличие синдрома Дауна и синдрома Эдвардса. База данных программы формировалась из листов опроса, содержащего информацию о беременной женщине: возраст, масса тела, срок беременности, курение, этническая принадлежность, число плодов, применение экстракорпорального оплодотворения, наличие/отсутствие сахарного диабета, данные УЗИ и показатели биохимических маркеров. На основании всего массива данных программа автоматически рассчитывает риск рождения ребенка с синдромом Дауна и синдромом Эдвардса, который указывается в цифрах. Пороговое значение риска составляет 1:250. Степень риска хромосомной патологии оценивали как высокую при соотношении 1:250 и ниже.

Для сбора материала исследования была разработана специальная анкета, которая содержала полную информацию о пациентке и плоде, включая репродуктивный и семейный анамнез, подробные сведения о проведении ультразвукового и биохимического скрининга в I и II триместрах беременности, данные об исходе беременности и состоянии новорожденного. Статистическая обработка данных выполнена на индивидуальном компьютере с помощью электронных таблиц Microsoft Excel и пакета прикладных программ Statistica for Windows v. 7.0. Для сравнения непрерывных данных использовали t-критерий Стьюдента, статистически значимыми считались различия при p<0,05 (95% уровень значимости).

Результаты

Первоочередной задачей настоящего исследования явился ретроспективный анализ точности исполнения женской консультацией приказов, регламентировавших проведение ПС беременных с 2007 по 2011 г.

Из 290 женщин, состоявших на учете по беременности с 2007 по 2011 г., в I триместре встала на учет 201 (69,3%) женщина, во II триместре —79 (27,1%) женщин, в III триместре — 10 (3,4%) женщин.

Ультразвуковой скрининг в I триместре беременности в положенные сроки был проведен 192 (66,2%) женщинам, УЗИ не проводилось 96 (33,8%) женщинам.

Биохимический скрининг в I триместре беременности был проведен 176 (60,7%) женщинам, 114 (39,3%) женщин не были обследованы.

Заключения об индивидуальном риске хромосомных аномалий (ХА) у плода в I триместре беременности имелись в амбулаторных картах только у 172 (59,3%) беременных женщин, у 118 (40,7%) они отсутствовали.

Во II триместре у 77 (26,6%) беременных сроки выполнения ультразвукового скрининга были нарушены, у 29 (10%) беременных УЗИ не проводилось вовсе. Только у 184 (63,4%) женщин, состоявших на учете по беременности, ультразвуковой скрининг был проведен в положенные сроки.

Что же касается биохимического скрининга, то образцы сыворотки крови были взяты своевременно только у 52 (18,0%) беременных, у 209 (72%) женщин сроки были нарушены, а у 29 (10,0%) исследование не проводилось вовсе.

Заключения лаборатории об индивидуальном риске ХА у плода имелись в амбулаторных картах только у 178 (61,4%) беременных, а у 112 (38,6%) беременных они отсутствовали.

Таким образом, ретроспективный анализ показал, что регламент проведения ПС систематически нарушался и, поскольку обследование в I и II триместрах беременности было проведено только 59,3 и 61,4% беременных женщин соответственно, его нельзя считать массовым.

С целью оценки результатов проводимого ПС были использованы данные о 172 беременных женщинах, в амбулаторных картах которых имелись заключения лаборатории об индивидуальном риске хромосомных аномалий у плода в I и II триместрах беременности. В табл. 1 представлены результаты ультразвукового скрининга в I триместре беременности, из которой явствует, что КТР плода определен у 161 (93,6%) беременной (у всех в пределах нормальных значений), у 11 (6,4%) беременных достоверная информация в амбулаторных картах отсутствовала. ТВП плода определена у 164 (95,3%) беременных: у 3 (1,8%) женщин ТВП составляла 3 мм и более, что является маркером хромосомной патологии, у 1 (0,6%) беременной определен порок развития плода — анэнцефалия. У 8 (4,7%) женщин достоверная информация в амбулаторных картах отсутствовала.

В табл. 2 представлены данные биохимического скрининга в I триместре беременности, которые свидетельствуют, что практически у всех женщин образцы крови были получены своевременно и своевременно определен уровень β-ХГ и PAPP-A, за исключением 3 (1,7%) женщин, в амбулаторных картах которых информация отсутствовала.

В результате комбинированного скрининга в I триместре беременности из 172 беременных 18 (10,4%) женщин были отнесены к группе риска: 9 (5,2%) с высоким риском ХА у плода и 9 (5,2%) — с пороговым риском. У остальных 154 (89,5%) риск ХА у плода был низким.

Все 18 (100%) беременных женщин, отнесенных к группе риска, были направлены в медико-генетическую консультацию (на второй уровень ПД), однако в амбулаторных картах имелась информация только о 2 (11,1%) из них, которым проводилась биопсия хориона. Хромосомная патология ни у кого выявлена не была, обе беременности были пролонгированы. Одна беременность с пороком развития плода (анэнцефалией) в I триместре была обоснованно прервана. Что же касается других 16 (88,9%) женщин из группы риска, то сведения о посещении и результатах медико-генетического консультирования в их амбулаторных картах в женской консультации отсутствовали. Это обстоятельство свидетельствует о недостаточной взаимосвязи между первым и вторым уровнем ПД.

Во II триместре беременности обследование плода проведено у 177 беременных женщин, при этом УЗИ в положенные сроки было выполнено только 99 (55,9%) из них, у 71 (40,1%) женщины сроки проведения УЗИ были нарушены. В результате УЗИ у 31 (17,5%) беременной была выявлена патология плода: внутриутробная задержка развития — у 3 (1,7%) женщин, многоводие — у 3 (1,7%), патология плаценты — у 24 (13,6%) и множественные пороки развития — у 1 (0,6%).

Биохимический скрининг во II триместре беременности был проведен 172 (97,2%) беременным в надлежащие сроки, у 5 (2,8%) женщин срок взятия образцов крови был нарушен. Фетальные маркеры АФП и β-ХГ были определены у всех беременных. В табл. 3 представлены результаты комбинированного скрининга 177 беременных, выраженные в значениях индивидуального риска развития дефектов невральной трубки и ХА (синдромов Эдвардса и Дауна) у плода, рассчитанных с помощью программы LifeCycle 2.2. Как видно, из 177 беременных, которым комбинированный скрининг был проведен во II триместре, к группе риска были отнесены 22 (12,4%) женщины: 2 (1,1%) с высоким риском развития дефекта невральной трубки, 6 (3,4%) — со средним и 14 (7,9%) — с высоким риском развития синдрома Дауна. При этом, если общее количество женщин, отнесенных к группе риска (22 женщины), принять за 100%, то в амбулаторных картах имелась информация только о 6 (27,8%) из них — тех, кто подвергался инвазивной процедуре (амниоцентезу) с целью взятия околоплодных вод для цитогенетического исследования (ни у кого хромосомная патология плода выявлена не была). Информация о других 16 (72,7%) женщинах в амбулаторных картах отсутствовала. Во II триместре у 1 (0,6%) женщины беременность была обоснованно прервана в связи с выявленными множественными пороками развития у плода, у 1 (0,6%) произошла внутриутробная гибель плода по причине фето-фетального синдрома 3-й степени, гестоза легкой степени и выраженного многоводия, 175 (98,9%) беременностей были пролонгированы.

Анализ эффективности пренатальной диагностики

С целью оценки эффективности ПД проведен сравнительный анализ исходов беременности в двух группах беременных женщин:

1) беременные, которым ПД проводилась и в амбулаторных картах которых имелись заключения лаборатории о риске ХА у плода;

2) беременные, которым ПД не проводилась и в амбулаторных картах которых заключения о риске ХА у плода отсутствовали (табл. 4).

Из табл. 4 явствует, что в обеих группах все показатели не имеют статистически значимых различий. Так, состояние подавляющего количества новорожденных (около 99,0%) в той и другой группе было оценено по шкале Апгар 7—10 баллов. В той и другой группе родилось по одному ребенку с синдромом Дауна. Полученные результаты свидетельствуют о низкой эффективности проводимой ПД.

Понимание значимости ПД врачами первого уровня

Учитывая то обстоятельство, что ПД врожденных и наследственных болезней является областью медицинской генетики, реализация которой на первом уровне находится в компетенции акушеров-гинекологов, была предпринята попытка выяснить степень осознанности врачами акушерами-гинекологами сущности и принципов организации этого вида деятельности. С этой целью были использованы тестовые задания (31 вопрос) по основным разделам ПД, заимствованные из сборника тестовых заданий по специальности «Генетика» [3]. В инкогнито-тестировании участвовали 7 врачей-гинекологов. В среднем количество правильных ответов составило 17,7 (56,2%), что свидетельствует о недостатке знаний у врачей акушеров-гинекологов, касающихся медико-генетических аспектов ПД.

Обсуждение

Во всех странах мира каждый 20-й ребенок рождается с врожденной патологией генетической природы. При этом 2—3 из 100 новорожденных появляются на свет с несовместимыми с жизнью или тяжелыми пороками развития, которые можно было бы выявить в период беременности. Поскольку 95% врожденных пороков развития, включая ХА, являются спорадическими, то в группе риска находится практически каждая беременная женщина. По этой причине ПД носит массовый характер [1, 2, 4, 6, 9].

Все большее распространение в практике работы медико-генетических учреждений в мире находит обследование беременных с помощью ПС в I триместре. Выявление патологии во II триместре беременности сопряжено с моральными проблемами и рядом акушерских осложнений, связанных с прерыванием беременности в поздние сроки [7, 8, 10, 13—16]

Анализ архивного материала женской консультации показал, что как раз массовый характер скрининга беременных в I триместре женская консультация не обеспечивает. Из общего количества женщин, состоявших на учете по беременности с 2007 по 2011 г., в I триместре встали на учет 69,3%, а ПС проведено 59,3% беременных женщин. Эти данные свидетельствуют, что организация исполнения приказа МЗ РФ № 457 и других приказов, регламентировавших ПД с 2007 по 2011 г., является неудовлетворительной и свидетельствует о недостаточной готовности амбулаторного звена акушерско-гинекологической службы к переходу на ПС только в I триместре.

В настоящее время доказаны практическая эффективность и целесообразность трехкратного ультразвукового скринингового обследования беременных на сроках 11—14, 20—22, 32—34 нед беременности [1, 7, 13]. По данным нашего исследования, во II триместре беременности сроки проведения УЗИ у 47,5% женщин были нарушены. Вместе с тем УЗИ все же позволило выявить у 17,5% беременных разнообразную патологию плода, что свидетельствует об актуальности ультразвукового скрининга во II триместре беременности, особенно для тех, кто не обследовался в I триместре.

Сравнительный анализ исходов беременности у женщин с проводившейся и не проводившейся ПД не выявил никаких достоверных различий по всем тестируемым параметрам. В той и другой группе родилось по одному ребенку с недиагностированным синдромом Дауна, что свидетельствует о низкой эффективности дородовых диагностических мероприятий по выявлению генетической патологии плода.

Проведенное тестирование врачей акушеров-гинекологов на знания основ ПД свидетельствует о недостатке их знаний. По-видимому, было бы целесообразно ввести в учебный процесс кафедр акушерства и гинекологии специальный курс ПД врожденных и наследственных болезней с основами медицинской генетики.

Выводы

1. Главной причиной низкой эффективности ПД врожденных и наследственных заболеваний является систематическое несоблюдение регламента проведения ПГ врачами амбулаторного звена акушерско-гинекологической службы, нарушающее его основные принципы — массовость, своевременность и полноценность.

2. Для повышения эффективности ПД врожденных и наследственных болезней требуются меры по совершенствованию деятельности амбулаторного звена акушерско-гинекологической службы, направленные на: 1) повышение компетентности врачей акушеров-гинекологов в медико-генетических вопросах ПД; 2) обеспечение информационной и мотивационной готовности беременных женщин к перинатальной профилактике; 3) оптимизацию взаимодействия между врачами первого и второго уровня.

Мы используем файлы cооkies для улучшения работы сайта. Оставаясь на нашем сайте, вы соглашаетесь с условиями

использования файлов cооkies. Чтобы ознакомиться с нашими Положениями о конфиденциальности и об использовании

файлов cookie, нажмите здесь.

- Research

- Open Access

- Published:

Molecular Cytogenetics

volume 15, Article number: 36 (2022)

Cite this article

-

26k Accesses

-

8 Citations

-

1 Altmetric

-

Metrics details

Abstract

Background

Non-invasive prenatal testing (NIPT) has had an incomparable triumph in prenatal diagnostics in the last decade. Over 1400 research articles have been published, predominantly praising the advantages of this test.

Methods

The present study identified among the 1400 papers 24 original and one review paper, which were suited to re-evaluate the efficacy of > 750,000 published NIPT-results. Special attention was given to false-positive and false-negative result-rates. Those were discussed under different aspects—mainly from a patient-perspective.

Results

A 27: 1 rate of false-positive compared to false-negative NIPT results was found. Besides, according to all reported, real-positive, chromosomally aberrant NIPT cases, 90% of those would have been aborted spontaneously before birth. These findings are here discussed under aspects like (i) How efficient is NIPT compared to first trimester screening? (ii) What are the differences in expectations towards NIPT from specialists and the public? and (iii) There should also be children born suffering from not by NIPT tested chromosomal aberrations; why are those never reported in all available NIPT studies?

Conclusions

Even though much research has been published on NIPT, unbiased figures concerning NIPT and first trimester screening efficacy are yet not available. While false positive rates of different NIPT tests maybe halfway accurate, reported false-negative rates are most likely too low. The latter is as NIPT-cases with negative results for tested conditions are yet not in detail followed up for cases with other genetic or teratogenic caused disorders. This promotes an image in public, that NIPT is suited to replace all invasive tests, and also to solve the problem of inborn errors in humans, if not now then in near future. Overall, it is worth discussing the usefulness of NIPT in practical clinical application. Particularly, asking for unbiased figures concerning the efficacy of first trimester-screening compared to NIPT, and for really comprehensive data on false-positive and false-negative NIPT results.

Introduction

The desire for prenatal information about the unborn child in the womb is probably as old as human history. While in ancient Greece, one could only consult an oracle or in the Middle Ages an astrologer, today’s contemporaries have actually the opportunity to look into the belly of the expectant mother. This is possible for a little over half a century, still, meanwhile it is standard to obtain even cell material from the fetus and analyze it for its genetic integrity. Thus, for the first time in human history, largely reliable statements on the genetic health of an unborn child are possible [1]. The latter seemed unimaginable even for science fiction authors in the 1970s [2].

We are currently experiencing an increased worldwide demand for the earliest possible testing of unborn children [1]. This has various causes as:

-

(i)

in industrialized countries many couples desire to have only one or at most two children, who then have to be healthy for sure;

-

(ii)

there is increasing age of the first-time mothers, which at the same time demands minimizing an age-associated increased risk for the birth of a child with an aneuploidy;

-

(iii)

in some so-called developing countries there is a desire of expectant parents to have male rather than female offspring and, if necessary, to be able to carry out abortion as early as possible; and/ or

-

(iv)

nowadays apparently simple applicable, fast and new non-invasive prenatal diagnostic procedures (PNDPs) are available and widely used [1, 2].

At present, various invasive and non-invasive PNDPs are available. Standard invasive procedures include chorionic villus sampling, amniocentesis and umbilical cord blood sampling. In all three invasive methods, placental or fetal cells are examined cytogenetically, molecular cytogenetically, and/or molecular genetically. Only then, it is possible to make unambiguous statements on questions such as: Is there a trisomy, monosomy or a chromosomal rearrangement? Does the expectant child have a genetic deletion or duplication (smaller than an entire chromosome)? Is there a specific gene mutation? After successful completion of the corresponding invasive diagnostic procedures, unequivocal yes or no answers for the presence or absence of a genetic defect can be expected [1]. All non-invasive PNDPs, on the other hand, are so-called screening methods; thus, only a probability statement as to whether the child to be has a specific genetic change or not. These statements always need checking, ultimately through an invasive PNDP. The non-invasive PNDPs include all ultra-sonographic approaches, all biochemical tests from maternal blood (such as the determination of alpha-fetoprotein = AFP, beta-human chorionic gonadotropin = ß-hCG or pregnancy-associated plasma protein-A = PAPPA), all combined methods, such as triple test or first trimester screening (FTS), and also the latest instrument in this “kit”—non-invasive prenatal testing (NIPT). The latter belongs to non-invasive PNDPs because (i) not the genetic material of the expectant child itself but of circulating free DNA derived from the placenta is examined here, and (ii) no clear yes or no answers are obtained, as in invasive PNDPs, but only statements of probability [1,2,3,4].

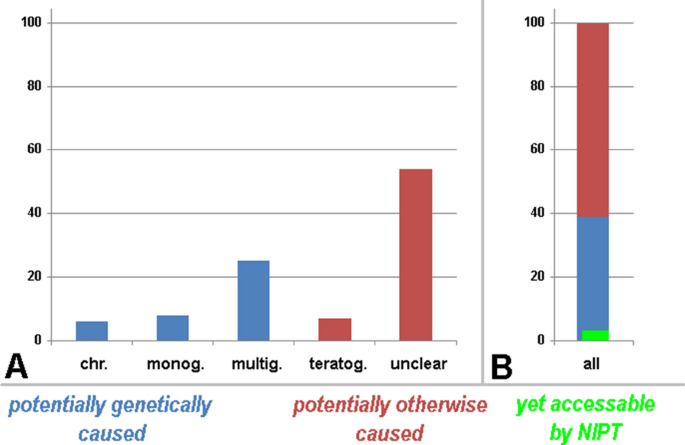

Between 3 and 6% of newborns have major inborn abnormalities, which classifies them as “individuals with congenital diseases/disease complexes/syndromes” [4]. If one considers the 3–6% mentioned as an “own population”, then a chromosomal disorder is present in ~ 6%, a teratogenic damage in ~ 7%, and a monogenetic or multigenetic disease in ~ 8% or ~ 25%, respectively. For the remainder ~ 54%, the diagnosis usually stays lifelong as suffering from an “idiopathic disorder”, i.e. the cause remains unclear (Fig. 1). Prenatally accessible is rather a large part of the chromosomal disorders and a very small percentage of the monogenetic disease; in the best-case scenario, a clear prenatal genetic diagnosis can only be expected for up to 10% of newborns with birth defects [1]—see also Fig. 1.

All newborns with clinical abnormalities and the causes of their problems are schematically depicted. In A the causes are specified as chromosomal aberrations (chr.), monogenetic (monog.), multigenetic (multig.), teratogenic (teratog.), and idiopathic (unclear) causes; in B all causes are summarized to 100%. It can be clearly seen that prenatally a maximum of 10% of the cases with clinical abnormalities can be characterized by a clear genetic cause; according to this review not more than 5% of these aberrant cases can be accessed by NIPT (green label)

Full size image

In this context, the general statements, promises and enthusiasm on the impact of NIPT on prenatal diagnostics needs some investigation, especially as there is a big market interest and a huge amount of money involved here [5,6,7]. Thus, here the efficacy to identify prenatally individuals with congenital diseases is re-evaluated on > 750,000 published NIPT-results predominantly from China, Europe and USA. The reported false-positive (FP) and false-negative (FN) rates were summarized and are discussed here under several aspects. Overall, it seems that the usefulness of NIPT in practical clinical application needs to be fundamentally re-considered.

Material and Methods

A Pubmed search for “non-invasive prenatal testing “identified slightly over 1400 publications in 05/2022; those were screened for studies reporting:

-

more than 500 NIPT cases,

-

on test results in (predominantly) singleton pregnancies,

-

on NIPT-settings testing for trisomy 13 (T13), trisomy 18 (T18), trisomy 21 (T21), numerical sex-chromosome-aberrations (SCAs) and/or rare autosomal trisomies (RATs),

-

on follow-up and/or an invasive PNDP to check for FP and FN cases in at least a subset of reported cases.

As listed in Additional file 1: Table S1 twenty-four corresponding studies were identified and included, originating from January 2017 to March 2022; also, a review (#25 in Additional file 1: Table S1) summarizing 32 corresponding studies before the year 2016 [8] was considered. Accordingly, > 750,000 NIPT cases are included and evaluated here.

Results

The > 750,000 NIPT cases included in Additional file 1: Table S1, Tables. 1 and 2 were studied to different extend for (1) T13, (2) T18, (3) T21, (4) SCAs and/or (5) RATs. Thus, a separate evaluation was done for each of the five indications as well as for those three studies addressing all five indications simultaneously. For the latter group (Tables. 1a and 2a, Additional file 1: Table S1) of 41,472 cases tested by NIPT, 520 had a positive result. For 460/520 NIPT-positive cases (= 91.63%) a second, confirmatory test was done and 217 turned out to be FP (47.17%). Three cases were stated as having been attributed with a FN NIPT result (with respect to the NIPT-positive cases this would be 0.65%). To calculate a FP and FN rate corresponding to performed NIPT-cases only 91.63% of 41,472 = 38,001 cases were considered, as for the remainder cases no second confirmatory test has had been done (for different reasons). Accordingly, for all in parallel for T13, T18, T21, SCAs and RATs tested NIPT cases got in 1.211% a FP and 0.0079 a FN result.

Full size table

Full size table

The chromosome wise data for most common autosomal trisomies (Tables 1b and 2b, Additional file 1: Table S1) in ~ 720,000 to 752,000 cases tested by NIPT gave the following picture: 44.25%, 18.52% and 9.79% of NIPT results for T13, T18 and T21, respectively were FP. Concerning all NIPT positive cases 1.89%, 2.07% and 0.59%, each, were FN for the corresponding trisomies. Calculated for overall 88.66% cases tested by a second test if NIPT-positive, this equals to 0.048%, 0.041% and 0.077% FP and 0.020%, 0.046% and 0.046% for T13, T18 and T21, correspondingly.

For SCAs and RATs (Tables. 1b and 2b, Additional file 1: Table S1) the FN rates are low—only 1 case for SCAs is reported and none for RATs. However, between 55.45 or 84.50 women with a positive NIPT indeed learn after an invasive test that these results were FP for SCAs or RATs. Among all correspondingly tested women, this affects between 0.248 and 0.206% of them.

Discussion

General thoughts

When specialists trained in the field of human/ =clinical genetics discuss ethical considerations in prenatal diagnostics, at least one thing is common sense: It is always only about the actual pregnant woman or couple and the actual fetus/future child what is considered and has to be discussed [9]. It is not about costs and overall advantages of a test for society, or the financing of a health system. However, since introduction of NIPT, always clearly stated to be a screening and no diagnostic test, dozens of papers have been out discussing exactly these points in a patient- and individual-far way. There are studies on the identification of “the most relevant cost-effectiveness threshold” for T21 when using NIPT from France [10] or China [11, 12], or on the fact that “NIPT screening has a high health economical value “[13]. Against this argumentation, oppose Prinds et al. [14], who state that a counsellor can not be a healthcare information sharing communicator, but that the individual couple needs to be in the center of the counselling. At the same time, there are ongoing discussions on the negative influence of NIPT on the rights of people with disabilities [15, 16], on women’s autonomy [17] and on different ways how to integrate NIPT into a national ethical landscape [18].

Overall, all this is striking, and especially the numerous publications on the potential benefits of NIPT for the economy of the national health systems are somewhat surprising, as no similar movements were there when FTS was introduced, which could not be commercialized similarly, but had already high detection rates as a non invasive prenatal setting. The same way astonishing is that majority of NIPT related papers are extremely enthusiastic about the high sensitivity and specificity of NIPT for T21, but no papers ask why at the same time values for T13 and T18 are much less good, and for SCAs, RATs and microdeletion/microduplication syndromes are almost devastating. In addition, papers showing that the trophoblast, which shall be used for NIPT to characterize single gene mutations, has much higher and different mutation rates than cells of the same fetus, are not discussed in corresponding literature [19]. The here touched suspicious points on NIPT-application are discussed below based on the data from this meta-analyses.

Conclusion: The uncritical attitude of the majority of articles reporting NIPT introduction and utilization as a pure success story is at least surprising, if not conspicuous.

Results of the present meta-analyses compared with literature data

Over 750,000 prenatal cases were reviewed here, to reevaluate the impact of NIPT on the detection of T13, T18, 21, SCAs and/or RATs. The possible differences in platforms and methods used for NIPT were intentionally not considered, even though they are well-known (to the author [20]). Such specification is normally also lacking in NIPT-related papers (see e.g. papers included as base for Additional file 1: Table S1). A more detailed, scientific unbiased comparison of capabilities of different NIPT-platforms would be critical, as in the literature it is rarely addressed [20] or done [21].

The two major findings of this meta-analysis are as follows:

-

In this meta-analyses a 27: 1 rate of FP compared to FN NIPT result was found (Table 1 — 2,039: 75). Others [22], reviewing data under the aspect that real efforts to find FN cases were undertaken, found a higher 7.3: 1 rate of FP (88%) to FN (12%). However, Samura and Okamoto [23] report a comparable 30: 1 FP/FN rate concerning all tested women. In most studies it is not detailed how much effort was invested to find FN-cases; considering also the below treated question “Where are the remainder ‘abnormal newborns’ in the NIPT studies?” the data of Hartwig et al. [22] possibly may be closer to the true FN-rate than that of the present and the Samura and Okamoto [23] study.

-

What in the present review was not considered are the also appearing 0.3-5.4% of NIPT cases which give no conclusive results (mainly due to underrepresentation of cffDNA (= cell free fetal DNA, as the placenta derived DNA is called in all literature,e in the sample), and the 0.1% of cases detecting maternal neoplasia or fetal chromosomal anomalies not intended to be checked [23]. Overall, one can expect to get for between 95 and 99% of the women tested with NIPT a negative result. In 1 to 5% the NIPT will be potentially positive and needs to be checked, which is done in the reviewed studies in ~ 90% of the cases.

-

Finding 1: According to the possibility of both FP and FN NIPT results, a positive as well as a negative NIPT-result with presence of sonographic abnormalities needs always to be checked by an invasive diagnostic.

-

According to Taylor-Phillips et al. [24] in the general obstetric population only can find in 100,000 pregnancies 40 cases with T13 (0.040%), 89 with T18 (0.089%) and 417 with T21 (0.417%). Nielsen and Wohlert [25] give a newborn frequency for SCAs of 0.0022%. Veropotvelyan and Nesterchuk [26] state for RATs 41% in missed abortions and in second trimester the percentage is 2.3%; data for newborns is not available. Moreover, the detection rate of numerical chromosomal aberrations in newborns overall is given as 0.6% [27]. As summarized in Table 3 NIPT for all numerical chromosomal aberrations detects 10.8 times more aberrant cases, than expected to be born. For T13, T18 and T21 two times as many than normally born children with these aneuploidies are picked up by NIPT, while for SCAs > 90 × more than abnormally born children are identified.

-

Finding 2: This data means that > 90% of abnormal fetuses identified by NIPT would end up in abortion during the further pregnancy.

Full size table

These findings and above-mentioned result lead to further questions as discussed now.

What is the data meaning for pregnant women with a positive NIPT result?

Interestingly, this point is hardly treated in the literature, and especially the fact that only 10% of by NIPT detected aberrant fetuses would have a chance to be born is—to the best of the authors’ knowledge—not mentioned a single time in the 1400 papers screened for this review. As shown in Table 2, there are two ways to look at the FP and FN NIPT results; in most—if not all publications—NIPT is praised for 1.211% FP and 0.0079% FN cases. The fact that acc. to the tested questions almost 10% of women with a positive NIPT for T21 and almost 85% of them with a positive RAT-oriented NIPT were falsely alarmed that their baby carries a chromosomal abnormality—which is overall not less than ~ 2000 women among 750,000 tested ones—is normally not considered, addressed, or discussed. However, this is a complete perversion of the individual and patient-oriented view of clinical genetics. The latter is being engraved, as in most cases no adequate pre-NIPT counselling was offered, and also post-NIPT counselling often is not helpful for the pregnant woman. Women having had a false positive NIPT normally state they would never do the test again [20]. Furthermore, it must be suggested that in some settings, a positive NIPT is not tested by a second approach, meaning that indeed unaffected fetuses are aborted – see also the following section.

Conclusion: NIPT can only be offered together with detailed, qualified genetic counselling on possibilities, problems, shortcuts and consequences of the test in case of a positive test result; otherwise NIPT will be taken into account by pregnant women having wrong expectations.

How much do pregnant women and their MDs trust the NIPT-result?

While performing a qualified NIPT includes always the mentioned qualified and extensive genetic counselling and an invasive test to confirm a positive result, it is at least doubtful if this guide is everywhere followed where NIPT is done. There are many reports of false positive NIPTs which were identified after the termination of a pregnancy (for review see [20], and also the Taiwanese study of Hsiao et al. [28] rather implies that pregnant women—guided by their MDs—rely on the NIPT completely, and tend to skip a confirmatory invasive test. Hsiao et al. [28] proudly presented that per 1 million women tested by double/ triple test with 1,051 suspected T21 cases 223 were born, while 1 million women tested with FTS identified 1680 suspected T21 cases with only 135 of them were born; this rate dropped in the next 1 million women with 1821 NIPT-positives for T21 to only 68 born T21 cases. For T18 the birth rates are given correspondingly as 19, 11, and 6 and for T13 as 8, 4 and 0. As the authors state, NIPT has a minimal false positive rate, and no own FP or FN data are provided in that report for their collective, these data at least raise the suspicion that invasive diagnostics was skipped in many of these cases and potentially healthy fetuses were terminated.

Besides this major trust of many MDs in NIPT results, the public and pregnant women are not well informed about the possibilities NIPT really comprises. This is only rarely systematically studied, but at least an influence of social class and education level on NIPT perception was shown in an US-study [29]. Another study done in Saudi Arabia showed that «the acceptance rate for NIPT is high, despite incomplete understanding of the benefits and limitations of the test» [30]; and similar results were obtained for pregnant women from China [31]. Bowman-Smart et al. [32] report for 34% of Australian women, interviewed after they gave birth to their child did not feel sufficiently informed of what the consequences of a positive NIPT result would have been.

Conclusion: Obstetricians and gynecologists need to be well-trained before offering NIPT to their patients. The public is relying on their expertise, which in this case is literally decisive over life or death. Also, MDs may get into juristic and financial troubles in case a FP or FN NIPT case becomes justiciable.

What is the data meaning for pregnant women with a negative NIPT?

In NIPT-literature, this point is hardly covered. Still, Hirose et al. [33] showed that ~ 7% of Japanese women with a negative NIPT afterwards “regretted receiving NIPT and blamed themselves for taking it”, a result also found by Lo et al. [34]. This was mainly attributed to a lack of trustworthy genetic counselling and psychological support, which is necessary as pregnant women who undergo NIPT have greater stress and anxiety than pregnant women who do not [35]. Comparable studies for other countries besides Japan are not available, and acc. to Nakamura et al. [36] it has not been checked, if also in other cultural settings “more than one-third of the pregnant women who had a negative NIPT result still experienced strong state anxiety (transient anxiety in each period), even after disclosure of their results” [33]. Most other studies did not specifically ask about the feelings of the women after the test; however, in an US-study [37] also 30% of pregnant women reported “elevated anxiety at the time of testing”. Furthermore, an Australian study [32] found that “95% of respondents indicated they would undergo NIPT in a future pregnancy” while the remainder 5% had negative experiences with NIPT testing. It is not further discussed, if the 5% mainly included the FP, FN or other cases with non-informative NIPT results, and similar peculiarities discussed above.

Again, it is a single Japanese study, which dealt with reasons why women were unsettled by NIPT, Yotsumoto et al. [38] detail four major reasons as follows:

-

lack of information from genetic counselling;

-

feeling of social pressure not to have a child with a disability, especially T21;

-

anxiety due to 2 weeks waiting for NIPT result coupled with an unawareness of doubts about the completeness of later obtained results;

-

general doubts as » ‘options in the case of a positive result’, ‘guilt towards the child’, ‘criticisms on NIPT from others,’ ‘denial of disabled people’, and ‘how to tell the child’ “.

Conclusion: Obstetricians and gynecologists need NOT leave alone the women to whom they offered the test; at least one additional consultation appointment should be offered to the advisor after the NIPT was sent off and before the result is there.

Where are the remainder ‘abnormal newborns’ in the NIPT studies?

In all here reviewed studies the pregnancies which showed no trisomies, SCAs, RATs (or other tested conditions not included in this review) were just reported as “normal after NIPT” or even “normal in follow-up”. As shown in Fig. 1 this is more than unlikely. Among 38,001 pregnancies (Table 1a) tested for all numerical whole chromosome aberrations with 37,755 NIPT negative cases there must be also children born suffering from microdeletion/ microduplication syndromes, monogenic and multigenetic disorders, as well as teratogenic and idiopathic conditions. If there are 246 cases found with real positive NIPT test—acc. to Table 3 about 25 of them would have been born acc. to data summarized in Taylor-Phillips et al. [24]. Among 38,001 born children, there must be an overall 1,140 to 2280 children with chromosomal aberrations, teratogenic damage, a monogenetic or multigenetic disease or an “idiopathic disorder” (Fig. 1).

Conclusion: NIPT studies must include all clinically abnormal cases—and if they group them all as idiopathic. Yet the published data is at least obviously incomplete, implying to the public a ‘wrong feeling of safety’.

What about NIPT for microdeletion/microduplication syndrome detection and for monogenic disorders?

NIPT has a high FP rate for SCAs and RATs of 0.21% to 0.25% for all tested pregnancies and concerning those women getting a positive NIPT result, it is at 55.45 and 84.5, respectively (Table. 2). The rates are similar for microdeletion/microduplication syndrome detection. FP-rates of ~ 50% are reported for DiGeorge syndrome [39], and they get higher the rarer the tested syndrome is [40]. Scharf [4] states that such a high false positive rate of NIPT for this kind of indication means at the same time an unnecessary high invasive PNDP rate. Thus, German guidelines do recommend not to use of NIPT for screening of microdeletion-/microduplication syndromes [41].

NIPT for detection of single gene disorders and corresponding point mutations are most often referred to as NIPS, to distinguish from ‘normal NIPT’. While few authors report on a 100% detection rate for mutations in small proof of principle studies [42], others are more skeptical. Already in 2009 it was highlighted that NIPT latest then becomes complex when fetus and mother have the same alleles, which are indistinguishable on cffDNA level [43]. Recently, the confined placental mosaicism problem being responsible for major parts of FP-NIPT results was also treated for point mutations. Coorens et al. [19] showed that “every placental sample represents a clonal expansion that is genetically distinct and exhibits a genomic landscape akin to that of childhood cancer in terms of mutation burden and mutational imprints.” The authors state that tremendous mutagenesis is rather rule than exception in the placenta.

Conclusion: NIPT for microdeletion-/microduplication syndromes is leading to that many FP results that it rather increases invasive testing than reduces it; chromosome microarray based on invasively obtained fetal tissue would be most informative here. NIPT for single gene mutations is due to biological peculiarities of the placenta a priori prone to FP results due to clonal developments similar as in cancer tissue.

Which data has a higher impact—NIPT or first trimester screening?

Conclusive data on the important question of which test is more reliable and more comprehensive, NIPT or FTS, are still lacking—there is only one mathematical algorithm based study [44] dealing with this problem. Kane et al. [44] suggest a 74% detection rate for T13, T18, T21 and 45,X for FTS compared to ~ 94% in NIPT. However, for other SCAs or RATs, FTS has a 35% detection rate compared to 0 or 13% in SNP- or non-SNP-based NIPT. Besides, Fries [45] showed in a small study on 153 cases picked up by FTS, that NIPT for T13, T18 and T21 would have missed at least 20% of those aberrant cases (like microdeletions or other chromosomal aberrations).

Nonetheless, while summarizing general prevalence thresholds of screening tests in obstetrics and gynecology Elfassy et al. [46] concluded that NIPT as it”is performed by sequencing fetal cell-free DNA in maternal circulation” (as we know this is not true) and “based on its inherent sensitivity and specificity parameters” (which are not supported by the present meta-analyses), NIPT to have a 2.4 times higher predictive value than FTS.

More realistically, Scharf [4] summarized that the detection rate of FTS for T21 is 95% and by NIPT 99%; thus he recommends T21-specific NIPT in combination with FTS, and especially with fetal sonography. Furthermore, Scharf [4] comes even to the conclusion that NIPT for T13 and T18 “no longer meet the quality criteria that are internationally applied to a screening procedure”.

Overall, two things are clear: (1) there was never a plea for FTS to finance by the health system like it was for NIPT, e.g. by Dutch MDs and scientists [47]; and (2) the best pickup-rate for chromosomal imbalances has the chromosome microarray combined with banding cytogenetics from amniocytes [48, 49].

Conclusion: An unbiased comparison of NIPT and FTS performance in the same patient population is necessary and still has not been published, even though data must be available.

Why not invasive testing?

It has already repeatedly been stated (e.g. [20]) that actual invasive PNDP cannot be compared with that 30 or 50 years ago. As nicely summarized by Salomon et al. [50]: “the invasive procedure-related risk of fetal loss of 1%, which was a major argument to increase the use of NIPT, has been reviewed drastically down to around 1/1000 or less “(see [45]).

Conclusion: The risk of abortion is no longer an argument for NIPT and against invasive PNDP.

Why are the false-positive rates so low for T21 and 2 to 6 times higher for all other aneuploidies?

All NIPT-related papers proudly present the almost perfect performance of the test for T21 with only an ~ 10% FP rate. The 2 to 9 times higher FP-rates for the remainder indications tested are only stated and hardly scientifically discussed. Some papers even neglect them and state that they found such reliable test systems and mathematical algorithms to come to 100% detection rates in NIPT for each indication and that they have no FP or FN results at all, which seems biologically impossible (keywords: confined placental mosaicism, vanishing twins, etc.) [51]. Most likely, especially the FP-data available from detailed NIPT results analyses could provide insights into trisomic rescue mechanisms in early embryogenesis. Eventually, even lesions could be learned which trisomies lead to fetal death first and which are more likely to be rescued, and why. Only one study states that 7 of 54 FP NIPT cases (13%) were due to vanishing twins [52].

Conclusion: NIPT was, is and will be a screening test. It detects placenta aberrations being present between the 11th and 25th weeks of gestation. All positive results must carefully be treated as possible HINT on an aberration in the fetus and a pointer that the early pregnancy might naturally end prematurely. Scientifically, the NIPT data has not been explored yet.

Conclusion

Having discussed all the problems of NIPT, for individual settings and considering the ethical considerations under which each human genetic counsellor (MD or non-MD) is trained, it is really hard to understand that actual papers start with sentences like: “NIPT has revolutionized the approach to prenatal diagnosis and, to date, it is the most superior screening method for the common autosomal aneuploidies” [53]; or with: “our findings show the diversity of clinical practice with regard to the incorporation of NIPT into prenatal screening algorithms, and suggest that the use of NIPT both as a first-line screening tool in the general obstetric population, and to screen for SCAs and CNVs, is becoming increasingly prevalent” [54]. There is an urgent need to come back to the couple, patient and unborn child perspective and away from cost and profit argumentations. Finally, it is necessary to publish unbiased figures concerning (a) efficacy to identify potentially genetically aberrant fetuses when using FTS compared to NIPT, (b) FP-rates of different NIPT tests, (c) FN-rates of different NIPT tests including all test failures, and all cases with not tested chromosomal aberrations, and not tested monogenetic, multigenetic, teratogenic, and idiopathic (unclear) causes of inborn defects. Overall, the most likely intentionally induced impression in public that NIPT is or at least will be the PNDP performed in future must be revised quickly, to preserve the credibility of prenatal and clinical genetic diagnostics in the long term.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].

Abbreviations

- AFP:

-

Alpha-fetoprotein

- ß-hCG:

-

Beta-human chorionic gonadotropin

- cffDNA:

-

Cell free fetal DNA

- DNA:

-

Deoxyribonucleic acid

- FN:

-

False-negative

- FP:

-

False-positive

- FTS:

-

First trimester-screening

- NIPT:

-

Non-invasive prenatal testing

- PAPPA:

-

Pregnancy associated plasma protein-A

- PNDP:

-

Prenatal diagnostic procedure

- RATs:

-

Rare autosomal trisomies

- SCAs:

-

Numerical sex-chromosome-aberrations

- T13:

-

Trisomy 13

- T18:

-

Trisomy 18

- T21:

-

Trisomy 21

References

-

Hixson L, Goel S, Schuber P, Faltas V, Lee J, Narayakkadan A, Leung H, Osborne J. An overview on prenatal screening for chromosomal aberrations. J Lab Autom. 2015;20:562–73.

Article

CAS

PubMedGoogle Scholar

-

Darouich AA, Liehr T, Weise A, Schlembach D, Schleußner E, Kiehntopf M, Schreyer I. Alpha-fetoprotein and its value for predicting pregnancy outcomes — a re-evaluation. J Prenat Med. 2015;9:18–23.

PubMed

PubMed CentralGoogle Scholar

-

Liehr T. Non-invasive prenatal testing, what patients do not learn, may be due to lack of specialist genetic training by gynecologists and obstetricians? Front Genet. 2021;12: 682980.

Article

PubMed

PubMed CentralGoogle Scholar

-

Scharf A. First trimester screening with biochemical markers and ultrasound in relation to non-invasive prenatal testing (NIPT). J Perinat Med. 2021;49:990–7.

Article

PubMedGoogle Scholar

-

Löwy I. Non-invasive prenatal testing: a diagnostic innovation shaped by commercial interests and the regulation conundrum. Soc Sci Med. 2020;20: 113064.

Google Scholar

-

Holloway K, Miller FA, Simms N. Industry, experts and the role of the “invisible college” in the dissemination of non-invasive prenatal testing in the US. Soc Sci Med. 2021;270: 113635.

Article

PubMedGoogle Scholar

-

Liehr T. 2019. Non-invasive prenatal testing – safer or simply more profitable? https://atlasofscience.org/non-invasive-prenatal-testing-safer-or-simply-more-profitable/

-

Iwarsson E, Jacobsson B, Dagerhamn J, Davidson T, Bernabé E, Heibert AM. Analysis of cell-free fetal DNA in maternal blood for detection of trisomy 21, 18 and 13 in a general pregnant population and in a high risk population — a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2017;96:7–18.

Article

CAS

PubMedGoogle Scholar

-

Schmitz D, Clarke A. Ethics experts and fetal patients: a proposal for modesty. BMC Med Ethics. 2021;22:161.

Article

PubMed

PubMed CentralGoogle Scholar

-

Blanquet M, Dreux S, Léger S, Sault C, Mourgues C, Laurichesse H, Lémery D, Vendittelli F, Debost-Legrand A, Muller F. Cost-effectiveness threshold of first-trimester Down syndrome maternal serum screening for the use of cell-free DNA as a second-tier screening test. Ann Biol Clin (Paris). 2021;79:331–8.

Google Scholar

-

Huang T, Gibbons C, Rashid S, Priston MK, Bedford HM, Mak-Tam E, Meschino WS. Prenatal screening for trisomy 21: a comparative performance and cost analysis of different screening strategies. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020;20:713.

Article

CAS

PubMed

PubMed CentralGoogle Scholar

-

Shang W, Wan Y, Chen J, Du Y, Huang J. Introducing the non-invasive prenatal testing for detection of Down syndrome in China: a cost-effectiveness analysis. BMJ Open. 2021;11: e046582.

Article

PubMed

PubMed CentralGoogle Scholar

-

Wang D, He J, Ma Y, Xi H, Zhang M, Huang H, Rao L, Zhang B, Mi C, Zhou B, Liao Z, Dai L, Ouyang X, Zhang Y, Wang H, Wang X, Zhang Z, Yao S, Tan Z, Yang J, Zhong W, Wang N, Liu J, Zhou L. [Retrospective and cost-effective analysis of the result of Changsha Municipal Public Welfare Program by Noninvasive Prenatal Testing]. Zhonghua Yi Xue Yi Chuan Xue Za Zhi. 2022;39:257-63.

-

Prinds C, der Wal JG, Crombag N, Martin L. Counselling for prenatal anomaly screening-A plea for integration of existential life questions. Patient Educ Couns. 2020;103:1657–61.

Article

PubMedGoogle Scholar

-

Zerres K, Rudnik-Schöneborn S, Holzgreve W. Do non-invasive prenatal tests promote discrimination against people with Down syndrome? What should be done? J Perinat Med. 2021;49:965–71.

Article

PubMedGoogle Scholar

-

Perrot A, Horn R. Preserving women’s reproductive autonomy while promoting the rights of people with disabilities?: the case of Heidi Crowter and Maire Lea-Wilson in the light of NIPT debates in England, France and Germany. J Med Ethics. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1136/medethics-2021-107912.

Article

PubMedGoogle Scholar

-

Salvesen KÅB, Glad R, Sitras V. Controversies in implementing non‐invasive prenatal testing in a public antenatal care program. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2022;101(6):577–80. https://doi.org/10.1111/aogs.14351.

Article

PubMedGoogle Scholar

-

Perrot A, Horn R. The ethical landscape(s) of non-invasive prenatal testing in England, France and Germany: findings from a comparative literature review. Euro J Hum Genet. 2021;30(6):676–81. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41431-021-00970-2.

Article

Google Scholar

-

Coorens THH, Oliver TRW, Sanghvi R, Sovio U, Cook E, Vento-Tormo R, Haniffa M, Young MD, Rahbari R, Sebire N, Campbell PJ, Charnock-Jones DS, Smith GCS, Behjati S. Inherent mosaicism and extensive mutation of human placentas. Nature. 2021;592:80–5.

Article

CAS

PubMed

PubMed CentralGoogle Scholar

-

Liehr T, Lauten A, Schneider U, Schleussner E, Weise A. Noninvasive prenatal testing (NIPT) – when is it advantageous to apply? Biomed Hub. 2017;2: 458432.

Article

Google Scholar

-

Paluoja P, Teder H, Ardeshirdavani A, Bayindir B, Vermeesch J, Salumets A, Krjutškov K, Palta P. Systematic evaluation of NIPT aneuploidy detection software tools with clinically validated NIPT samples. PLoS Comput Biol. 2021;17: e1009684.

Article

CAS

PubMed

PubMed CentralGoogle Scholar

-

Hartwig TS, Ambye L, Sørensen S, Jørgensen FS. Discordant non-invasive prenatal testing (NIPT) — a systematic review. Prenat Diagn. 2017;37:527–39.

Article

PubMedGoogle Scholar

-

Samura O, Okamoto A. Causes of aberrant non-invasive prenatal testing for aneuploidy: a systematic review. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;59:16–20.

Article

PubMedGoogle Scholar

-

Taylor-Phillips S, Freeman K, Geppert J, Agbebiyi A, Uthman OA, Madan J, Clarke A, Quenby S, Clarke A. Accuracy of non-invasive prenatal testing using cell-free DNA for detection of Down, Edwards and Patau syndromes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2016;6: e010002.

Article

PubMed

PubMed CentralGoogle Scholar

-

Nielsen J, Wohlert M. Sex chromosome abnormalities found among 34,910 newborn children: results from a 13-year incidence study in Arhus. Denmark Birth Defects Orig Artic Ser. 1990;26:209–23.

CAS

PubMedGoogle Scholar

-

Veropotvelyan N, Nesterchuk D. Rare trisomies: frequency, range, lethality at embryonic and fetal stages of prenatal development. ScienceRise Med Sci. 2017;2:45–51. https://doi.org/10.15587/2519-4798.2017.94385.

Article

Google Scholar

-

Jacobs PA, Browne C, Gregson N, Joyce C, White H. Estimates of the frequency of chromosome abnormalities detectable in unselected newborns using moderate levels of banding. J Med Genet. 1992;29:103–8.

Article

CAS

PubMed

PubMed CentralGoogle Scholar

-

Hsiao CH, Chen CH, Cheng PJ, Shaw SW, Chu WC, Chen RC. The impact of prenatal screening tests on prenatal diagnosis in Taiwan from 2006 to 2019: a regional cohort study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2022;22:23.

Article

PubMed

PubMed CentralGoogle Scholar

-

Montgomery S, Thayer ZM. The influence of experiential knowledge and societal perceptions on decision-making regarding non-invasive prenatal testing (NIPT). BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020;20:630.

Article

PubMed

PubMed CentralGoogle Scholar

-

Bawazeer S, AlSayed M, Kurdi W, Balobaid A. Knowledge and attitudes regarding non-invasive prenatal testing among women in Saudi Arabia. Prenat Diagn. 2021;41:1343–50.

Article

PubMedGoogle Scholar

-

Yang J, Chen M, Ye X, Chen F, Li Y, Li N, Wu W, Sun J. A cross-sectional survey of pregnant women’s knowledge of chromosomal aneuploidy and microdeletion and microduplication syndromes. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2021;256:82–90.

Article

PubMedGoogle Scholar

-

Bowman-Smart H, Savulescu J, Mand C, Gyngell C, Pertile MD, Lewis S, Delatycki MB. “Small cost to pay for peace of mind”: women’s experiences with non-invasive prenatal testing. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2019;59:649–55.

Article

PubMed

PubMed CentralGoogle Scholar

-

Hirose T, Shirato N, Izumi M, Miyagami K, Sekizawa A. Postpartum questionnaire survey of women who tested negative in a non-invasive prenatal testing: examining negative emotions towards the test. J Hum Genet. 2021;66:579–84.

Article

PubMedGoogle Scholar

-

Lo TK, Chan KY, Kan AS, So PL, Kong CW, Mak SL, Lee CN. Decision outcomes in women offered noninvasive prenatal test (NIPT) for positive down screening results. J Matern Fet Neonatal Med. 2019;32:348–50.

Article

Google Scholar

-

Suzumori N, Ebara T, Kumagai K, Goto S, Yamada Y, Kamijima M, Sugiura-Ogasawara M. Non-specific psychological distress in women undergoing noninvasive prenatal testing because of advanced maternal age. Prenat Diagn. 2014;34:1055–60.

Article

PubMedGoogle Scholar

-

Nakamura M, Ogawa M, Taura Y, Kawasaki S, Kawakami K, Motoshima S. Anxiety levels in women receiving a negative NIPT result: influence of psychosocial adaptation in pregnancy. Jpn J Genet Couns. 2016;37:187–95.

Google Scholar

-