Как и многие языки программирования, Rust призывает разработчика определенным способом обрабатывать ошибки. Вообще, существует два общих подхода обработки ошибок: с помощью исключений и через возвращаемые значения. И Rust предпочитает возвращаемые значения.

В этой статье мы намерены подробно изложить работу с ошибками в Rust. Более того, мы попробуем раз за разом погружаться в обработку ошибок с различных сторон, так что под конец у вас будет уверенное практическое представление о том, как все это сходится воедино.

В наивной реализации обработка ошибок в Rust может выглядеть многословной и раздражающей. Мы рассмотрим основные камни преткновения, а также продемонстрируем, как сделать обработку ошибок лаконичной и удобной, пользуясь стандартной библиотекой.

Содержание

Эта статья очень длинная, в основном потому, что мы начнем с самого начала — рассмотрения типов-сумм (sum type) и комбинаторов, и далее попытаемся последовательно объяснить подход Rust к обработке ошибок. Так что разработчики, которые имеют опыт работы с другими выразительными системами типов, могут свободно перескакивать от раздела к разделу.

- Основы

- Объяснение unwrap

- Тип Option

- Совмещение значений Option<T>

- Тип Result

- Преобразование строки в число

- Создание псевдонима типа Result

- Короткое отступление: unwrap — не обязательно зло

- Работа с несколькими типами ошибок

- Совмещение Option и Result

- Ограничения комбинаторов

- Преждевременный return

- Макрос try!

- Объявление собственного типа ошибки

- Типажи из стандартной библиотеки, используемые для обработки ошибок

- Типаж Error

- Типаж From

- Настоящий макрос try!

- Совмещение собственных типов ошибок

- Рекомендации для авторов библиотек

- Заключение

Основы

Обработку ошибок можно рассматривать как вариативный анализ того, было ли некоторое вычисление выполнено успешно или нет. Как будет показано далее, ключом к удобству обработки ошибок является сокращение количества явного вариативного анализа, который должен выполнять разработчик, сохраняя при этом код легко сочетаемым с другим кодом (composability).

(Примечание переводчика: Вариативный анализ – это один из наиболее общеприменимых методов аналитического мышления, который заключается в рассмотрении проблемы, вопроса или некоторой ситуации с точки зрения каждого возможного конкретного случая. При этом рассмотрение по отдельности каждого такого случая является достаточным для того, чтобы решить первоначальный вопрос.

Важным аспектом такого подхода к решению проблем является то, что такой анализ должен быть исчерпывающим (exhaustive). Другими словами, при использовании вариативного анализа должны быть рассмотрены все возможные случаи.

В Rust вариативный анализ реализуется с помощью синтаксической конструкции match. При этом компилятор гарантирует, что такой анализ будет исчерпывающим: если разработчик не рассмотрит все возможные варианты заданного значения, программа не будет скомпилирована.)

Сохранять сочетаемость кода важно, потому что без этого требования мы могли бы просто получать panic всякий раз, когда мы сталкивались бы с чем-то неожиданным. (panic вызывает прерывание текущего потока и, в большинстве случаев, приводит к завершению всей программы.) Вот пример:

// Попробуйте угадать число от 1 до 10.

// Если заданное число соответствует тому, что мы загадали, возвращается true.

// В противном случае возвращается false.

fn guess(n: i32) -> bool {

if n < 1 || n > 10 {

panic!("Неверное число: {}", n);

}

n == 5

}

fn main() {

guess(11);

}

Если попробовать запустить этот код, то программа аварийно завершится с сообщением вроде этого:

thread '<main>' panicked at 'Неверное число: 11', src/bin/panic-simple.rs:6

Вот другой, менее надуманный пример. Программа, которая принимает число в качестве аргумента, удваивает его значение и печатает на экране.

use std::env;

fn main() {

let mut argv = env::args();

let arg: String = argv.nth(1).unwrap(); // ошибка 1

let n: i32 = arg.parse().unwrap(); // ошибка 2

println!("{}", 2 * n);

}

Если вы запустите эту программу без параметров (ошибка 1) или если первый параметр будет не целым числом (ошибка 2), программа завершится паникой, так же, как и в первом примере.

Обработка ошибок в подобном стиле подобна слону в посудной лавке. Слон будет нестись в направлении, в котором ему вздумается, и крушить все на своем пути.

Объяснение unwrap

В предыдущем примере мы утверждали, что программа будет просто паниковать, если будет выполнено одно из двух условий для возникновения ошибки, хотя, в отличии от первого примера, в коде программы нет явного вызова panic. Тем не менее, вызов panic встроен в вызов unwrap.

Вызывать unwrap в Rust подобно тому, что сказать: «Верни мне результат вычислений, а если произошла ошибка, просто паникуй и останавливай программу». Мы могли бы просто показать исходный код функции unwrap, ведь это довольно просто, но перед этим мы должны разобратся с типами Option и Result. Оба этих типа имеют определенный для них метод unwrap.

Тип Option

Тип Option объявлен в стандартной библиотеке:

enum Option<T> {

None,

Some(T),

}

Тип Option — это способ выразить возможность отсутствия чего бы то ни было, используя систему типов Rust. Выражение возможности отсутствия через систему типов является важной концепцией, поскольку такой подход позволяет компилятору требовать от разработчика обрабатывать такое отсутствие. Давайте взглянем на пример, который пытается найти символ в строке:

// Поиск Unicode-символа `needle` в `haystack`. Когда первый символ найден,

// возвращается побайтовое смещение для этого символа. Иначе возвращается `None`.

fn find(haystack: &str, needle: char) -> Option<usize> {

for (offset, c) in haystack.char_indices() {

if c == needle {

return Some(offset);

}

}

None

}

Обратите внимание, что когда эта функция находит соответствующий символ, она возвращает не просто offset. Вместо этого она возвращает Some(offset). Some — это вариант или конструктор значения для типа Option. Его можно интерпретировать как функцию типа fn<T>(value: T) -> Option<T>. Соответственно, None — это также конструктор значения, только у него нет параметров. Его можно интерпретировать как функцию типа fn<T>() -> Option<T>.

Может показаться, что мы подняли много шума из ничего, но это только половина истории. Вторая половина — это использование функции find, которую мы написали. Давайте попробуем использовать ее, чтобы найти расширение в имени файла.

fn main() {

let file_name = "foobar.rs";

match find(file_name, '.') {

None => println!("Расширение файла не найдено."),

Some(i) => println!("Расширение файла: {}", &file_name[i+1..]),

}

}

Этот код использует сопоставление с образцом чтобы выполнить вариативный анализ для возвращаемого функцией find значения Option<usize>. На самом деле, вариативный анализ является единственным способом добраться до значения, сохраненного внутри Option<T>. Это означает, что вы, как разработчик, обязаны обработать случай, когда значение Option<T> равно None, а не Some(t).

Но подождите, как насчет unwrap, который мы до этого использовали? Там не было никакого вариативного анализа! Вместо этого, вариативный анализ был перемещен внутрь метода unwrap. Вы можете сделать это самостоятельно, если захотите:

enum Option<T> {

None,

Some(T),

}

impl<T> Option<T> {

fn unwrap(self) -> T {

match self {

Option::Some(val) => val,

Option::None =>

panic!("called `Option::unwrap()` on a `None` value"),

}

}

}

Метод unwrap абстрагирует вариативный анализ. Это именно то, что делает unwrap удобным в использовании. К сожалению, panic! означает, что unwrap неудобно сочетать с другим кодом: это слон в посудной лавке.

Совмещение значений Option<T>

В предыдущем примере мы рассмотрели, как можно воспользоватся find для того, чтобы получить расширение имени файла. Конечно, не во всех именах файлов можно найти ., так что существует вероятность, что имя некоторого файла не имеет расширения. Эта возможность отсутствия интерпретируется на уровне типов через использование Option<T>. Другими словами, компилятор заставит нас рассмотреть возможность того, что расширение не существует. В нашем случае мы просто печатаем сообщение об этом.

Получение расширения имени файла — довольно распространенная операция, так что имеет смысл вынести код в отдельную функцию:

// Возвращает расширение заданного имени файла, а именно все символы,

// идущие за первым вхождением `.` в имя файла.

// Если в `file_name` нет ни одного вхождения `.`, возвращается `None`.

fn extension_explicit(file_name: &str) -> Option<&str> {

match find(file_name, '.') {

None => None,

Some(i) => Some(&file_name[i+1..]),

}

}

(Подсказка: не используйте этот код. Вместо этого используйте метод extension из стандартной библиотеки.)

Код выглядит простым, но его важный аспект заключается в том, что функция find заставляет нас рассмотреть вероятность отсутствия значения. Это хорошо, поскольку это означает, что компилятор не позволит нам случайно забыть о том варианте, когда в имени файла отсутствует расширение. С другой стороны, каждый раз выполнять явный вариативный анализ, подобно тому, как мы делали это в extension_explicit, может стать немного утомительным.

На самом деле, вариативный анализ в extension_explicit является очень распространенным паттерном: если Option<T> владеет определенным значением T, то выполнить его преобразование с помощью функции, а если нет — то просто вернуть None.

Rust поддерживает параметрический полиморфизм, так что можно очень легко объявить комбинатор, который абстрагирует это поведение:

fn map<F, T, A>(option: Option<T>, f: F) -> Option<A> where F: FnOnce(T) -> A {

match option {

None => None,

Some(value) => Some(f(value)),

}

}

В действительности, map определен в стандартной библиотеке как метод Option<T>.

Вооружившись нашим новым комбинатором, мы можем переписать наш метод extension_explicit так, чтобы избавиться от вариативного анализа:

// Возвращает расширение заданного имени файла, а именно все символы,

// идущие за первым вхождением `.` в имя файла.

// Если в `file_name` нет ни одного вхождения `.`, возвращается `None`.

fn extension(file_name: &str) -> Option<&str> {

find(file_name, '.').map(|i| &file_name[i+1..])

}

Есть еще одно поведение, которое можно часто встретить — это использование значения по-умолчанию в случае, когда значение Option равно None. К примеру, ваша программа может считать, что расширение файла равно rs в случае, если на самом деле оно отсутствует.

Легко представить, что этот случай вариативного анализа не специфичен только для расширений файлов — такой подход может работать с любым Option<T>:

fn unwrap_or<T>(option: Option<T>, default: T) -> T {

match option {

None => default,

Some(value) => value,

}

}

Хитрость только в том, что значение по-умолчанию должно иметь тот же тип, что и значение, которое может находится внутри Option<T>. Использование этого метода элементарно:

fn main() {

assert_eq!(extension("foobar.csv").unwrap_or("rs"), "csv");

assert_eq!(extension("foobar").unwrap_or("rs"), "rs");

}

(Обратите внимание, что unwrap_or объявлен как метод Option<T> в стандартной библиотеке, так что мы воспользовались им вместо функции, которую мы объявили ранее. Не забудьте также изучить более общий метод unwrap_or_else).

Существует еще один комбинатор, на который, как мы думаем, стоит обратить особое внимание: and_then. Он позволяет легко сочетать различные вычисления, которые допускают возможность отсутствия. Пример — большая часть кода в этом разделе, который связан с определением расширения заданного имени файла. Чтобы делать это, нам для начала необходимо узнать имя файла, которое как правило извлекается из файлового пути. Хотя большинство файловых путей содержат имя файла, подобное нельзя сказать обо всех файловых путях. Примером могут послужить пути ., .. или /.

Таким образом, мы определили задачу нахождения расширения заданного файлового пути. Начнем с явного вариативного анализа:

fn file_path_ext_explicit(file_path: &str) -> Option<&str> {

match file_name(file_path) {

None => None,

Some(name) => match extension(name) {

None => None,

Some(ext) => Some(ext),

}

}

}

fn file_name(file_path: &str) -> Option<&str> {

unimplemented!() // опустим реализацию

}

Можно подумать, мы могли бы просто использовать комбинатор map, чтобы уменьшить вариативный анализ, но его тип не совсем подходит. Дело в том, что map принимает функцию, которая делает что-то только с внутренним значением. Результат такой функции всегда оборачивается в Some. Вместо этого, нам нужен метод, похожий map, но который позволяет вызывающему передать еще один Option. Его общая реализация даже проще, чем map:

fn and_then<F, T, A>(option: Option<T>, f: F) -> Option<A>

where F: FnOnce(T) -> Option<A> {

match option {

None => None,

Some(value) => f(value),

}

}

Теперь мы можем переписать нашу функцию file_path_ext без явного вариативного анализа:

fn file_path_ext(file_path: &str) -> Option<&str> {

file_name(file_path).and_then(extension)

}

Тип Option имеет много других комбинаторов определенных в стандартной библиотеке. Очень полезно просмотреть этот список и ознакомиться с доступными методами — они не раз помогут вам сократить количество вариативного анализа. Ознакомление с этими комбинаторами окупится еще и потому, что многие из них определены с аналогичной семантикой и для типа Result, о котором мы поговорим далее.

Комбинаторы делают использование типов вроде Option более удобным, ведь они сокращают явный вариативный анализ. Они также соответствуют требованиям сочетаемости, поскольку они позволяют вызывающему обрабатывать возможность отсутствия результата собственным способом. Такие методы, как unwrap, лишают этой возможности, ведь они будут паниковать в случае, когда Option<T> равен None.

Тип Result

Тип Result также определен в стандартной библиотеке:

enum Result<T, E> {

Ok(T),

Err(E),

}

Тип Result — это продвинутая версия Option. Вместо того, чтобы выражать возможность отсутствия, как это делает Option, Result выражает возможность ошибки. Как правило, ошибки необходимы для объяснения того, почему результат определенного вычисления не был получен. Строго говоря, это более общая форма Option. Рассмотрим следующий псевдоним типа, который во всех смыслах семантически эквивалентен реальному Option<T>:

type Option<T> = Result<T, ()>;

Здесь второй параметр типа Result фиксируется и определяется через () (произносится как «unit» или «пустой кортеж»). Тип () имеет ровно одно значение — (). (Да, это тип и значение этого типа, которые выглядят одинаково!)

Тип Result — это способ выразить один из двух возможных исходов вычисления. По соглашению, один исход означает ожидаемый результат или «Ok«, в то время как другой исход означает исключительную ситуацию или «Err«.

Подобно Option, тип Result имеет метод unwrap, определенный в стандартной библиотеке. Давайте объявим его самостоятельно:

impl<T, E: ::std::fmt::Debug> Result<T, E> {

fn unwrap(self) -> T {

match self {

Result::Ok(val) => val,

Result::Err(err) =>

panic!("called `Result::unwrap()` on an `Err` value: {:?}", err),

}

}

}

Это фактически то же самое, что и определение Option::unwrap, за исключением того, что мы добавили значение ошибки в сообщение panic!. Это делает отладку проще, но это вынуждает нас требовать от типа-параметра E (который представляет наш тип ошибки) реализации Debug. Поскольку подавляющее большинство типов должны реализовывать Debug, обычно на практике такое ограничение не мешает. (Реализация Debug для некоторого типа просто означает, что существует разумный способ печати удобочитаемого описания значения этого типа.)

Окей, давайте перейдем к примеру.

Преобразование строки в число

Стандартная библиотека Rust позволяет элементарно преобразовывать строки в целые числа. На самом деле это настолько просто, что возникает соблазн написать что-то вроде:

fn double_number(number_str: &str) -> i32 {

2 * number_str.parse::<i32>().unwrap()

}

fn main() {

let n: i32 = double_number("10");

assert_eq!(n, 20);

}

Здесь вы должны быть скептически настроены по-поводу вызова unwrap. Если строку нельзя распарсить как число, вы получите панику:

thread '<main>' panicked at 'called `Result::unwrap()` on an `Err` value: ParseIntError { kind: InvalidDigit }', /home/rustbuild/src/rust-buildbot/slave/beta-dist-rustc-linux/build/src/libcore/result.rs:729

Это довольно неприятно, и если бы подобное произошло в используемой вами библиотеке, вы могли бы небезосновательно разгневаться. Так что нам стоит попытаться обработать ошибку в нашей функции, и пусть вызывающий сам решит что с этим делать. Это означает необходимость изменения типа, который возвращается double_number. Но на какой? Чтобы понять это, необходимо посмотреть на сигнатуру метода parse из стандартной библиотеки:

impl str {

fn parse<F: FromStr>(&self) -> Result<F, F::Err>;

}

Хмм. По крайней мере мы знаем, что должны использовать Result. Вполне возможно, что метод мог возвращать Option. В конце концов, строка либо парсится как число, либо нет, не так ли? Это, конечно, разумный путь, но внутренняя реализация знает почему строка не распарсилась как целое число. (Это может быть пустая строка, или неправильные цифры, слишком большая или слишком маленькая длина и т.д.) Таким образом, использование Result имеет смысл, ведь мы хотим предоставить больше информации, чем просто «отсутствие». Мы хотим сказать, почему преобразование не удалось. Вам стоит рассуждать похожим образом, когда вы сталкиваетесь с выбором между Option и Result. Если вы можете предоставить подробную информацию об ошибке, то вам, вероятно, следует это сделать. (Позже мы поговорим об этом подробнее.)

Хорошо, но как мы запишем наш тип возвращаемого значения? Метод parse является обобщенным (generic) для всех различных типов чисел из стандартной библиотеки. Мы могли бы (и, вероятно, должны) также сделать нашу функцию обобщенной, но давайте пока остановимся на конкретной реализации. Нас интересует только тип i32, так что нам стоит найти его реализацию FromStr (выполните поиск в вашем браузере по строке «FromStr») и посмотреть на его ассоциированный тип Err. Мы делаем это чтобы определить конкретный тип ошибки. В данном случае, это std::num::ParseIntError. Наконец, мы можем переписать нашу функцию:

use std::num::ParseIntError;

fn double_number(number_str: &str) -> Result<i32, ParseIntError> {

match number_str.parse::<i32>() {

Ok(n) => Ok(2 * n),

Err(err) => Err(err),

}

}

fn main() {

match double_number("10") {

Ok(n) => assert_eq!(n, 20),

Err(err) => println!("Error: {:?}", err),

}

}

Неплохо, но нам пришлось написать гораздо больше кода! И нас опять раздражает вариативный анализ.

Комбинаторы спешат на помощь! Подобно Option, Result имеет много комбинаторов, определенных в качестве методов. Существует большой список комбинаторов, общих между Result и Option. И map входит в этот список:

use std::num::ParseIntError;

fn double_number(number_str: &str) -> Result<i32, ParseIntError> {

number_str.parse::<i32>().map(|n| 2 * n)

}

fn main() {

match double_number("10") {

Ok(n) => assert_eq!(n, 20),

Err(err) => println!("Error: {:?}", err),

}

}

Все ожидаемые методы реализованы для Result, включая unwrap_or и and_then. Кроме того, поскольку Result имеет второй параметр типа, существуют комбинаторы, которые влияют только на значение ошибки, такие как map_err (аналог map) и or_else (аналог and_then).

Создание псевдонима типа Result

В стандартной библиотеке можно часто увидеть типы вроде Result<i32>. Но постойте, ведь мы определили Result с двумя параметрами типа. Как мы можем обойти это, указывая только один из них? Ответ заключается в определении псевдонима типа Result, который фиксирует один из параметров конкретным типом. Обычно фиксируется тип ошибки. Например, наш предыдущий пример с преобразованием строк в числа можно переписать так:

use std::num::ParseIntError;

use std::result;

type Result<T> = result::Result<T, ParseIntError>;

fn double_number(number_str: &str) -> Result<i32> {

unimplemented!();

}

Зачем мы это делаем? Что ж, если у нас есть много функций, которые могут вернуть ParseIntError, то гораздо удобнее определить псевдоним, который всегда использует ParseIntError, так что мы не будем повторяться все время.

Самый заметный случай использования такого подхода в стандартной библиотеке — псевдоним io::Result. Как правило, достаточно писать io::Result<T>, чтобы было понятно, что вы используете псевдоним типа из модуля io, а не обычное определение из std::result. (Этот подход также используется для fmt::Result)

Короткое отступление: unwrap — не обязательно зло

Если вы были внимательны, то возможно заметили, что я занял довольно жесткую позицию по отношению к методам вроде unwrap, которые могут вызвать panic и прервать исполнение вашей программы. В основном, это хороший совет.

Тем не менее, unwrap все-таки можно использовать разумно. Факторы, которые оправдывают использование unwrap, являются несколько туманными, и разумные люди могут со мной не согласиться. Я кратко изложу свое мнение по этому вопросу:

- Примеры и «грязный» код. Когда вы пишете просто пример или быстрый скрипт, обработка ошибок просто не требуется. Для подобных случаев трудно найти что-либо удобнее чем

unwrap, так что здесь его использование очень привлекательно. - Паника указывает на ошибку в программе. Если логика вашего кода должна предотвращать определенное поведение (скажем, получение элемента из пустого стека), то использование

panicтакже допустимо. Дело в том, что в этом случае паника будет сообщать о баге в вашей программе. Это может происходить явно, например от неудачного вызоваassert!, или происходить потому, что индекс по массиву находится за пределами выделенной памяти.

Вероятно, это не исчерпывающий список. Кроме того, при использовании Option зачастую лучше использовать метод expect. Этот метод делает ровно то же, что и unwrap, за исключением того, что в случае паники напечатает ваше сообщение. Это позволит лучше понять причину ошибки, ведь будет показано конкретное сообщение, а не просто «called unwrap on a None value».

Мой совет сводится к следующему: используйте здравый смысл. Есть причины, по которым слова вроде «никогда не делать X» или «Y считается вредным» не появятся в этой статье. У любых решений существуют компромиссы, и это ваша задача, как разработчика, определить, что именно является приемлемым для вашего случая. Моя цель состоит только в том, чтобы помочь вам оценить компромиссы как можно точнее.

Теперь, когда мы рассмотрели основы обработки ошибок в Rust и разобрались с unwrap, давайте подробнее изучим стандартную библиотеку.

Работа с несколькими типами ошибок

До этого момента мы расматривали обработку ошибок только для случаев, когда все сводилось либо только к Option<T>, либо только к Result<T, SomeError>. Но что делать, когда у вас есть и Option, и Result? Или если у вас есть Result<T, Error1> и Result<T, Error2>? Наша следующуя задача — обработка композиции различных типов ошибок, и это будет главной темой на протяжении всей этой статьи.

Совмещение Option и Result

Пока что мы говорили о комбинаторах, определенных для Option, и комбинаторах, определенных для Result. Эти комбинаторы можно использовать для того, чтобы сочетать результаты различных вычислений, не делая подробного вариативного анализа.

Конечно, в реальном коде все происходит не так гладко. Иногда у вас есть сочетания типов Option и Result. Должны ли мы прибегать к явному вариативному анализу, или можно продолжить использовать комбинаторы?

Давайте на время вернемся к одному из первых примеров в этой статье:

use std::env;

fn main() {

let mut argv = env::args();

let arg: String = argv.nth(1).unwrap(); // ошибка 1

let n: i32 = arg.parse().unwrap(); // ошибка 2

println!("{}", 2 * n);

}

Учитывая наши знания о типах Option и Result, а также их различных комбинаторах, мы можем попытаться переписать этот код так, чтобы ошибки обрабатывались должным образом, и программа не паниковала в случае ошибки.

Ньюанс заключается в том, что argv.nth(1) возвращает Option, в то время как arg.parse() возвращает Result. Они не могут быть скомпонованы непосредственно. Когда вы сталкиваетесь одновременно с Option и Result, обычно наилучшее решение — преобразовать Option в Result. В нашем случае, отсутствие параметра командной строки (из env::args()) означает, что пользователь не правильно вызвал программу. Мы могли бы просто использовать String для описания ошибки. Давайте попробуем:

use std::env;

fn double_arg(mut argv: env::Args) -> Result<i32, String> {

argv.nth(1)

.ok_or("Please give at least one argument".to_owned())

.and_then(|arg| arg.parse::<i32>().map_err(|err| err.to_string()))

}

fn main() {

match double_arg(env::args()) {

Ok(n) => println!("{}", n),

Err(err) => println!("Error: {}", err),

}

}

Раcсмотрим пару новых моментов на этом примере. Во-первых, использование комбинатора Option::ok_or. Это один из способов преобразования Option в Result. Такое преобразование требует явного определения ошибки, которую необходимо вернуть в случае, когда значение Option равно None. Как и для всех комбинаторов, которые мы рассматривали, его объявление очень простое:

fn ok_or<T, E>(option: Option<T>, err: E) -> Result<T, E> {

match option {

Some(val) => Ok(val),

None => Err(err),

}

}

Второй новый комбинатор, который мы использовали — Result::map_err. Это то же самое, что и Result::map, за исключением того, функция применяется к ошибке внутри Result. Если значение Result равно Оk(...), то оно возвращается без изменений.

Мы используем map_err, потому что нам необходимо привести все ошибки к одинаковому типу (из-за нашего использования and_then). Поскольку мы решили преобразовывать Option<String> (из argv.nth(1)) в Result<String, String>, мы также обязаны преобразовывать ParseIntError из arg.parse() в String.

Ограничения комбинаторов

Работа с IO и анализ входных данных — очень типичные задачи, и это то, чем лично я много занимаюсь с Rust. Так что мы будем использовать IO и различные процедуры анализа как примеры обработки ошибок.

Давайте начнем с простого. Поставим задачу открыть файл, прочесть все его содержимое и преобразовать это содержимое в число. После этого нужно будет умножить значение на 2 и распечатать результат.

Хоть я и пытался убедить вас не использовать unwrap, иногда бывает полезным для начала написать код с unwrap. Это позволяет сосредоточиться на проблеме, а не на обработке ошибок, и это выявляет места, где надлежащая обработка ошибок необходима. Давайте начнем с того, что напишем просто работающий код, а затем отрефакторим его для лучшей обработки ошибок.

use std::fs::File;

use std::io::Read;

use std::path::Path;

fn file_double<P: AsRef<Path>>(file_path: P) -> i32 {

let mut file = File::open(file_path).unwrap(); // ошибка 1

let mut contents = String::new();

file.read_to_string(&mut contents).unwrap(); // ошибка 2

let n: i32 = contents.trim().parse().unwrap(); // ошибка 3

2 * n

}

fn main() {

let doubled = file_double("foobar");

println!("{}", doubled);

}

(Замечание: Мы используем AsRef по тем же причинам, почему он используется в std::fs::File::open. Это позволяет удобно использовать любой тип строки в качестве пути к файлу.)

У нас есть три потенциальные ошибки, которые могут возникнуть:

- Проблема при открытии файла.

- Проблема при чтении данных из файла.

- Проблема при преобразовании данных в число.

Первые две проблемы определяются типом std::io::Error. Мы знаем это из типа возвращаемого значения методов std::fs::File::open и std::io::Read::read_to_string. (Обратите внимание, что они оба используют концепцию с псевдонимом типа Result, описанную ранее. Если вы кликните на тип Result, вы увидите псевдоним типа, и следовательно, лежащий в основе тип io::Error.) Третья проблема определяется типом std::num::ParseIntError. Кстати, тип io::Error часто используется по всей стандартной библиотеке. Вы будете видеть его снова и снова.

Давайте начнем рефакторинг функции file_double. Для того, чтобы эту функцию можно было сочетать с остальным кодом, она не должна паниковать, если какие-либо из перечисленных выше ошибок действительно произойдут. Фактически, это означает, что функция должна возвращать ошибку, если любая из возможных операций завершилась неудачей. Проблема состоит в том, что тип возвращаемого значения сейчас i32, который не дает нам никакого разумного способа сообщить об ошибке. Таким образом, мы должны начать с изменения типа возвращаемого значения с i32 на что-то другое.

Первое, что мы должны решить: какой из типов использовать: Option или Result? Мы, конечно, могли бы с легкостью использовать Option. Если какая-либо из трех ошибок происходит, мы могли бы просто вернуть None. Это будет работать, и это лучше, чем просто паниковать, но мы можем сделать гораздо лучше. Вместо этого, мы будем сообщать некоторые детали о возникшей проблеме. Поскольку мы хотим выразить возможность ошибки, мы должны использовать Result<i32, E>. Но каким должен быть тип E? Поскольку может возникнуть два разных типа ошибок, мы должны преобразовать их к общему типу. Одним из таких типов является String. Давайте посмотрим, как это отразится на нашем коде:

use std::fs::File;

use std::io::Read;

use std::path::Path;

fn file_double<P: AsRef<Path>>(file_path: P) -> Result<i32, String> {

File::open(file_path)

.map_err(|err| err.to_string())

.and_then(|mut file| {

let mut contents = String::new();

file.read_to_string(&mut contents)

.map_err(|err| err.to_string())

.map(|_| contents)

})

.and_then(|contents| {

contents.trim().parse::<i32>()

.map_err(|err| err.to_string())

})

.map(|n| 2 * n)

}

fn main() {

match file_double("foobar") {

Ok(n) => println!("{}", n),

Err(err) => println!("Ошибка: {}", err),

}

}

Выглядит немного запутанно. Может потребоваться довольно много практики, прежде вы сможете писать такое. Написание кода в таком стиле называется следованием за типом. Когда мы изменили тип возвращаемого значения file_double на Result<i32, String>, нам пришлось начать подбирать правильные комбинатороы. В данном случае мы использовали только три различных комбинатора: and_then, map и map_err.

Комбинатор and_then используется для объединения по цепочке нескольких вычислений, где каждое вычисление может вернуть ошибку. После открытия файла есть еще два вычисления, которые могут завершиться неудачей: чтение из файла и преобразование содержимого в число. Соответственно, имеем два вызова and_then.

Комбинатор map используется, чтобы применить функцию к значению Ok(...) типа Result. Например, в самом последнем вызове, map умножает значение Ok(...) (типа i32) на 2. Если ошибка произошла до этого момента, эта операция была бы пропущена. Это следует из определения map.

Комбинатор map_err — это уловка, которая позволяют всему этому заработать. Этот комбинатор, такой же, как и map, за исключением того, что применяет функцию к Err(...) значению Result. В данном случае мы хотим привести все наши ошибки к одному типу — String. Поскольку как io::Error, так и num::ParseIntError реализуют ToString, мы можем вызвать метод to_string, чтобы выполнить преобразование.

Не смотря на все сказанное, код по-прежнему выглядит запутанным. Мастерство использования комбинаторов является важным, но у них есть свои недостатки. Давайте попробуем другой подход: преждевременный возврат.

Преждевременный return

Давайте возьмем код из предыдущего раздела и перепишем его с применением раннего возврата. Ранний return позволяет выйти из функции досрочно. Мы не можем выполнить return для file_double внутри замыкания, поэтому нам необходимо вернуться к явному вариативному анализу.

use std::fs::File;

use std::io::Read;

use std::path::Path;

fn file_double<P: AsRef<Path>>(file_path: P) -> Result<i32, String> {

let mut file = match File::open(file_path) {

Ok(file) => file,

Err(err) => return Err(err.to_string()),

};

let mut contents = String::new();

if let Err(err) = file.read_to_string(&mut contents) {

return Err(err.to_string());

}

let n: i32 = match contents.trim().parse() {

Ok(n) => n,

Err(err) => return Err(err.to_string()),

};

Ok(2 * n)

}

fn main() {

match file_double("foobar") {

Ok(n) => println!("{}", n),

Err(err) => println!("Ошибка: {}", err),

}

}

Кто-то может обосновано не согласиться с тем, что этот код лучше, чем тот, который использует комбинаторы, но если вы не знакомы с комбинаторами, на мой взгляд, этот код будет выглядеть проще. Он выполняет явный вариативный анализ с помощью match и if let. Если происходит ошибка, мы просто прекращаем выполнение функции и возвращаем ошибку (после преобразования в строку).

Разве это не шаг назад? Ранее мы говорили, что ключ к удобной обработке ошибок — сокращение явного вариативного анализа, но здесь мы вернулись к тому, с чего начинали. Оказывается, существует несколько способов его уменьшения. И комбинаторы — не единственный путь.

Макрос try!

Краеугольный камень обработки ошибок в Rust — это макрос try!. Этот макрос абстрагирует анализ вариантов так же, как и комбинаторы, но в отличие от них, он также абстрагирует поток выполнения. А именно, он умеет абстрагировать идею досрочного возврата, которую мы только что реализовали.

Вот упрощенное определение макроса `try!:

macro_rules! try {

($e:expr) => (match $e {

Ok(val) => val,

Err(err) => return Err(err),

});

}

(Реальное определение выглядит немного сложнее. Мы обсудим это далее).

Использование макроса try! может очень легко упростить наш последний пример. Поскольку он выполняет анализ вариантов и досрочной возврат из функции, мы получаем более плотный код, который легче читать:

use std::fs::File;

use std::io::Read;

use std::path::Path;

fn file_double<P: AsRef<Path>>(file_path: P) -> Result<i32, String> {

let mut file = try!(File::open(file_path).map_err(|e| e.to_string()));

let mut contents = String::new();

try!(file.read_to_string(&mut contents).map_err(|e| e.to_string()));

let n = try!(contents.trim().parse::<i32>().map_err(|e| e.to_string()));

Ok(2 * n)

}

fn main() {

match file_double("foobar") {

Ok(n) => println!("{}", n),

Err(err) => println!("Ошибка: {}", err),

}

}

Вызов map_err по-прежнему необходим, учитывая наше определение try!, поскольку ошибки все еще должны быть преобразованы в String. Хорошей новостью является то, что в ближайшее время мы узнаем, как убрать все эти вызовы map_err! Плохая новость состоит в том, что для этого нам придется кое-что узнать о паре важных типажей из стандартной библиотеки.

Объявление собственного типа ошибки

Прежде чем мы погрузимся в аспекты некоторых типажей из стандартной библиотеки, связанных с ошибками, я бы хотел завершить этот раздел отказом от использования String как типа ошибки в наших примерах.

Использование String в том стиле, в котором мы использовали его в предыдущих примерах удобно потому, что достаточно легко конвертировать любые ошибки в строки, или даже создавать свои собственные ошибки на ходу. Тем не менее, использование типа String для ошибок имеет некоторые недостатки.

Первый недостаток в том, что сообщения об ошибках, как правило, загромождают код. Можно определять сообщения об ошибках в другом месте, но это поможет только если вы необыкновенно дисциплинированны, поскольку очень заманчиво вставлять сообщения об ошибках прямо в код. На самом деле, мы именно этим и занимались в предыдущем примере.

Второй и более важный недостаток заключается в том, что использование String чревато потерей информации. Другими словами, если все ошибки будут преобразованы в строки, то когда мы будем возвращать их вызывающей стороне, они не будут иметь никакого смысла. Единственное разумное, что вызывающая сторона может сделать с ошибкой типа String — это показать ее пользователю. Безусловно, можно проверить строку по значению, чтобы определить тип ошибки, но такой подход не может похвастаться надежностью. (Правда, в гораздо большей степени это недостаток для библиотек, чем для конечных приложений).

Например, тип io::Error включает в себя тип io::ErrorKind, который является структурированными данными, представляющими то, что пошло не так во время выполнения операции ввода-вывода. Это важно, поскольку может возникнуть необходимость по-разному реагировать на различные причины ошибки. (Например, ошибка BrokenPipe может изящно завершать программу, в то время как ошибка NotFound будет завершать программу с кодом ошибки и показывать соответствующее сообщение пользователю.) Благодаря io::ErrorKind, вызывающая сторона может исследовать тип ошибки с помощью вариативного анализа, и это значительно лучше попытки вычленить детали об ошибке из String.

Вместо того, чтобы использовать String как тип ошибки в нашем предыдущем примере про чтение числа из файла, мы можем определить свой собственный тип, который представляет ошибку в виде структурированных данных. Мы постараемся не потерять никакую информацию от изначальных ошибок на тот случай, если вызывающая сторона захочет исследовать детали.

Идеальным способом представления одного варианта из многих является определение нашего собственного типа-суммы с помощью enum. В нашем случае, ошибка представляет собой либо io::Error, либо num::ParseIntError, из чего естественным образом вытекает определение:

use std::io;

use std::num;

// Мы реализуем `Debug` поскольку, по всей видимости, все типы должны реализовывать `Debug`.

// Это дает нам возможность получить адекватное и читаемое описание значения CliError

#[derive(Debug)]

enum CliError {

Io(io::Error),

Parse(num::ParseIntError),

}

Осталось только немного подогнать наш код из примера. Вместо преобразования ошибок в строки, мы будем просто конвертировать их в наш тип CliError, используя соответствующий конструктор значения:

use std::fs::File;

use std::io::Read;

use std::path::Path;

fn file_double<P: AsRef<Path>>(file_path: P) -> Result<i32, CliError> {

let mut file = try!(File::open(file_path).map_err(CliError::Io));

let mut contents = String::new();

try!(file.read_to_string(&mut contents).map_err(CliError::Io));

let n: i32 = try!(contents.trim().parse().map_err(CliError::Parse));

Ok(2 * n)

}

fn main() {

match file_double("foobar") {

Ok(n) => println!("{}", n),

Err(err) => println!("Ошибка: {:?}", err),

}

}

Единственное изменение здесь — замена вызова map_err(|e| e.to_string()) (который преобразовывал ошибки в строки) на map_err(CliError::Io) или map_err(CliError::Parse). Теперь вызывающая сторона определяет уровень детализации сообщения об ошибке для конечного пользователя. В действительности, использование String как типа ошибки лишает вызывающего возможности выбора, в то время использование собственного типа enum, на подобие CliError, дает вызывающему тот же уровень удобства, который был ранее, и кроме этого структурированные данные, описывающие ошибку.

Практическое правило заключается в том, что необходимо определять свой собственный тип ошибки, а тип String для ошибок использовать в крайнем случае, в основном когда вы пишете конечное приложение. Если вы пишете библиотеку, определение своего собственного типа ошибки наиболее предпочтительно. Таким образом, вы не лишите пользователя вашей библиотеки возможности выбирать наиболее предпочтительное для его конкретного случая поведение.

Типажи из стандартной библиотеки, используемые для обработки ошибок

Стандартная библиотека определяет два встроенных типажа, полезных для обработки ошибок std::error::Error и std::convert::From. И если Error разработан специально для создания общего описания ошибки, то типаж From играет широкую роль в преобразовании значений между различными типами.

Типаж Error

Типаж Error объявлен в стандартной библиотеке:

use std::fmt::{Debug, Display};

trait Error: Debug + Display {

/// A short description of the error.

fn description(&self) -> &str;

/// The lower level cause of this error, if any.

fn cause(&self) -> Option<&Error> { None }

}

Этот типаж очень обобщенный, поскольку предполагается, что он должен быть реализован для всех типов, которые представляют собой ошибки. Как мы увидим дальше, он нам очень пригодится для написания сочетаемого кода. Этот типаж, как минимум, позволяет выполнять следующие вещи:

- Получать строковое представление ошибки для разработчика (

Debug). - Получать понятное для пользователя представление ошибки (

Display). - Получать краткое описание ошибки (метод

description). - Изучать по цепочке первопричину ошибки, если она существует (метод

cause).

Первые две возможности возникают в результате того, что типаж Error требует в свою очередь реализации типажей Debug и Display. Последние два факта исходят из двух методов, определенных в самом Error. Мощь Еrror заключается в том, что все существующие типы ошибок его реализуют, что в свою очередь означает что любые ошибки могут быть сохранены как типажи-объекты (trait object). Обычно это выглядит как Box<Error>, либо &Error. Например, метод cause возвращает &Error, который как раз является типажом-объектом. Позже мы вернемся к применению Error как типажа-объекта.

В настоящее время достаточно показать пример, реализующий типаж Error. Давайте воспользуемся для этого типом ошибки, который мы определили в предыдущем разделе:

use std::io;

use std::num;

// Мы реализуем `Debug` поскольку, по всей видимости, все типы должны реализовывать `Debug`.

// Это дает нам возможность получить адекватное и читаемое описание значения CliError

#[derive(Debug)]

enum CliError {

Io(io::Error),

Parse(num::ParseIntError),

}

Данный тип ошибки отражает возможность возникновения двух других типов ошибок: ошибка работы с IО или ошибка преобразования строки в число. Определение ошибки может отражать столько других видов ошибок, сколько необходимо, за счет добавления новых вариантов в объявлении enum.

Реализация Error довольно прямолинейна и главным образом состоит из явного анализа вариантов:

use std::error;

use std::fmt;

impl fmt::Display for CliError {

fn fmt(&self, f: &mut fmt::Formatter) -> fmt::Result {

match *self {

// Оба изначальных типа ошибок уже реализуют `Display`,

// так что мы можем использовать их реализации

CliError::Io(ref err) => write!(f, "IO error: {}", err),

CliError::Parse(ref err) => write!(f, "Parse error: {}", err),

}

}

}

impl error::Error for CliError {

fn description(&self) -> &str {

// Оба изначальных типа ошибок уже реализуют `Error`,

// так что мы можем использовать их реализацией

match *self {

CliError::Io(ref err) => err.description(),

CliError::Parse(ref err) => err.description(),

}

}

fn cause(&self) -> Option<&error::Error> {

match *self {

// В обоих случаях просходит неявное преобразование значения `err`

// из конкретного типа (`&io::Error` или `&num::ParseIntError`)

// в типаж-обьект `&Error`. Это работает потому что оба типа реализуют `Error`.

CliError::Io(ref err) => Some(err),

CliError::Parse(ref err) => Some(err),

}

}

}

Хочется отметить, что это очень типичная реализация Error: реализация методов description и cause в соответствии с каждым возможным видом ошибки.

Типаж From

Типаж std::convert::From объявлен в стандартной библиотеке:

trait From<T> {

fn from(T) -> Self;

}

Очень просто, не правда ли? Типаж From чрезвычайно полезен, поскольку создает общий подход для преобразования из определенного типа Т в какой-то другой тип (в данном случае, «другим типом» является тип, реализующий данный типаж, или Self). Самое важное в типаже From — множество его реализаций, предоставляемых стандартной библиотекой.

Вот несколько простых примеров, демонстрирующих работу From:

let string: String = From::from("foo");

let bytes: Vec<u8> = From::from("foo");

let cow: ::std::borrow::Cow<str> = From::from("foo");

Итак, From полезен для выполнения преобразований между строками. Но как насчет ошибок? Оказывается, существует одна важная реализация:

impl<'a, E: Error + 'a> From<E> for Box<Error + 'a>

Эта реализация говорит, что любой тип, который реализует Error, можно конвертировать в типаж-объект Box<Error>. Выглядит не слишком впечатляюще, но это очень полезно в общем контексте.

Помните те две ошибки, с которыми мы имели дело ранее, а именно, io::Error and num::ParseIntError? Поскольку обе они реализуют Error, они также работают с From:

use std::error::Error;

use std::fs;

use std::io;

use std::num;

// Получаем значения ошибок

let io_err: io::Error = io::Error::last_os_error();

let parse_err: num::ParseIntError = "not a number".parse::<i32>().unwrap_err();

// Собственно, конвертация

let err1: Box<Error> = From::from(io_err);

let err2: Box<Error> = From::from(parse_err);

Здесь нужно разобрать очень важный паттерн. Переменные err1 и err2 имеют одинаковый тип — типаж-объект. Это означает, что их реальные типы скрыты от компилятора, так что по факту он рассматривает err1 и err2 как одинаковые сущности. Кроме того, мы создали err1 и err2, используя один и тот же вызов функции — From::from. Мы можем так делать, поскольку функция From::from перегружена по ее аргументу и возвращаемому типу.

Эта возможность очень важна для нас, поскольку она решает нашу предыдущую проблему, позволяя эффективно конвертировать разные ошибки в один и тот же тип, пользуясь только одной функцией.

Настало время вернуться к нашему старому другу — макросу try!.

Настоящий макрос try!

До этого мы привели такое определение try!:

macro_rules! try {

($e:expr) => (match $e {

Ok(val) => val,

Err(err) => return Err(err),

});

}

Но это не настоящее определение. Реальное определение можно найти в стандартной библиотеке:

macro_rules! try {

($e:expr) => (match $e {

Ok(val) => val,

Err(err) => return Err(::std::convert::From::from(err)),

});

}

Здесь есть одно маленькое, но очень важное изменение: значение ошибки пропускается через вызов From::from. Это делает макрос try! очень мощным инструментом, поскольку он дает нам возможность бесплатно выполнять автоматическое преобразование типов.

Вооружившись более мощным макросом try!, давайте взглянем на код, написанный нами ранее, который читает файл и конвертирует его содержимое в число:

use std::fs::File;

use std::io::Read;

use std::path::Path;

fn file_double<P: AsRef<Path>>(file_path: P) -> Result<i32, String> {

let mut file = try!(File::open(file_path).map_err(|e| e.to_string()));

let mut contents = String::new();

try!(file.read_to_string(&mut contents).map_err(|e| e.to_string()));

let n = try!(contents.trim().parse::<i32>().map_err(|e| e.to_string()));

Ok(2 * n)

}

Ранее мы говорили, что мы можем избавиться от вызовов map_err. На самом деле, все что мы должны для этого сделать — это найти тип, который работает с From. Как мы увидели в предыдущем разделе, From имеет реализацию, которая позволяет преобразовать любой тип ошибки в Box<Error>:

use std::error::Error;

use std::fs::File;

use std::io::Read;

use std::path::Path;

fn file_double<P: AsRef<Path>>(file_path: P) -> Result<i32, Box<Error>> {

let mut file = try!(File::open(file_path));

let mut contents = String::new();

try!(file.read_to_string(&mut contents));

let n = try!(contents.trim().parse::<i32>());

Ok(2 * n)

}

Мы уже очень близки к идеальной обработке ошибок. Наш код имеет очень мало накладных расходов из-за обработки ошибок, ведь макрос try! инкапсулирует сразу три вещи:

- Вариативный анализ.

- Поток выполнения.

- Преобразование типов ошибок.

Когда все эти три вещи объединены вместе, мы получаем код, который не обременен комбинаторами, вызовами unwrap или постоянным анализом вариантов.

Но осталась одна маленькая деталь: тип Box<Error> не несет никакой информации. Если мы возвращаем Box<Error> вызывающей стороне, нет никакой возможности (легко) узнать базовый тип ошибки. Ситуация, конечно, лучше, чем со String, посольку появилась возможность вызывать методы, вроде description или cause, но ограничение остается: Box<Error> не предоставляет никакой информации о сути ошибки. (Замечание: Это не совсем верно, поскольку в Rust есть инструменты рефлексии во время выполнения, которые полезны при некоторых сценариях, но их рассмотрение выходит за рамки этой статьи).

Настало время вернуться к нашему собственному типу CliError и связать все в одно целое.

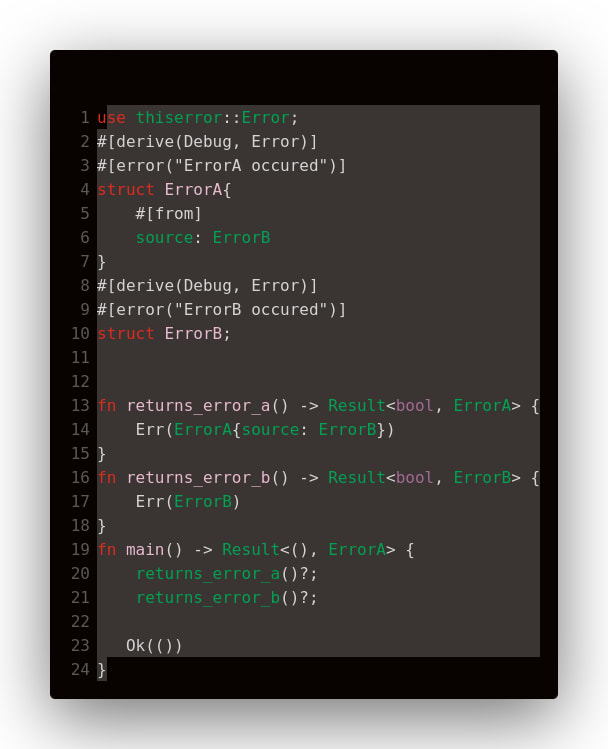

Совмещение собственных типов ошибок

В последнем разделе мы рассмотрели реальный макрос try! и то, как он выполняет автоматическое преобразование значений ошибок с помощью вызова From::from. В нашем случае мы конвертировали ошибки в Box<Error>, который работает, но его значение скрыто для вызывающей стороны.

Чтобы исправить это, мы используем средство, с которым мы уже знакомы: создание собственного типа ошибки. Давайте вспомним код, который считывает содержимое файла и преобразует его в целое число:

use std::fs::File;

use std::io::{self, Read};

use std::num;

use std::path::Path;

// Мы реализуем `Debug` поскольку, по всей видимости, все типы должны реализовывать `Debug`.

// Это дает нам возможность получить адекватное и читаемое описание значения CliError

#[derive(Debug)]

enum CliError {

Io(io::Error),

Parse(num::ParseIntError),

}

fn file_double_verbose<P: AsRef<Path>>(file_path: P) -> Result<i32, CliError> {

let mut file = try!(File::open(file_path).map_err(CliError::Io));

let mut contents = String::new();

try!(file.read_to_string(&mut contents).map_err(CliError::Io));

let n: i32 = try!(contents.trim().parse().map_err(CliError::Parse));

Ok(2 * n)

}

Обратите внимание, что здесь у нас еще остались вызовы map_err. Почему? Вспомните определения try! и From. Проблема в том, что не существует такой реализации From, которая позволяет конвертировать типы ошибок io::Error и num::ParseIntError в наш собственный тип CliError. Но мы можем легко это исправить! Поскольку мы определили тип CliError, мы можем также реализовать для него типаж From:

use std::io;

use std::num;

impl From<io::Error> for CliError {

fn from(err: io::Error) -> CliError {

CliError::Io(err)

}

}

impl From<num::ParseIntError> for CliError {

fn from(err: num::ParseIntError) -> CliError {

CliError::Parse(err)

}

}

Все эти реализации позволяют From создавать значения CliError из других типов ошибок. В нашем случае такое создание состоит из простого вызова конструктора значения. Как правило, это все что нужно.

Наконец, мы можем переписать file_double:

use std::fs::File;

use std::io::Read;

use std::path::Path;

fn file_double<P: AsRef<Path>>(file_path: P) -> Result<i32, CliError> {

let mut file = try!(File::open(file_path));

let mut contents = String::new();

try!(file.read_to_string(&mut contents));

let n: i32 = try!(contents.trim().parse());

Ok(2 * n)

}

Единственное, что мы сделали — это удалили вызовы map_err. Они нам больше не нужны, поскольку макрос try! выполняет From::from над значениями ошибок. И это работает, поскольку мы предоставили реализации From для всех типов ошибок, которые могут возникнуть.

Если бы мы изменили нашу функцию file_double таким образом, чтобы она начала выполнять какие-то другие операции, например, преобразовать строку в число с плавающей точкой, то мы должны были бы добавить новый вариант к нашему типу ошибок:

use std::io;

use std::num;

enum CliError {

Io(io::Error),

ParseInt(num::ParseIntError),

ParseFloat(num::ParseFloatError),

}

И добавить новую реализацию для From:

use std::num;

impl From<num::ParseFloatError> for CliError {

fn from(err: num::ParseFloatError) -> CliError {

CliError::ParseFloat(err)

}

}

Вот и все!

Рекомендации для авторов библиотек

Если в вашей библиотеке могут возникать специфические ошибки, то вы наверняка должны определить для них свой собственный тип. На ваше усмотрение вы можете сделать его внутреннее представление публичным (как ErrorKind), или оставить его скрытым (подобно ParseIntError). Независимо от того, что вы предпримете, считается хорошим тоном обеспечить по крайней мере некоторую информацию об ошибке помимо ее строкового представления. Но, конечно, все зависит от конкретных случаев использования.

Как минимум, вы скорее всего должны реализовать типаж Error. Это даст пользователям вашей библиотеки некоторую минимальную гибкость при совмещении ошибок. Реализация типажа Error также означает, что пользователям гарантируется возможность получения строкового представления ошибки (это следует из необходимости реализации fmt::Debug и fmt::Display).

Кроме того, может быть полезным реализовать From для ваших типов ошибок. Это позволит вам (как автору библиотеки) и вашим пользователям совмещать более детальные ошибки. Например, csv::Error реализует From для io::Error и byteorder::Error.

Наконец, на свое усмотрение, вы также можете определить псевдоним типа Result, особенно, если в вашей библиотеке определен только один тип ошибки. Такой подход используется в стандартной библиотеке для io::Result и fmt::Result.

Заключение

Поскольку это довольно длинная статья, не будет лишним составить короткий конспект по обработке ошибок в Rust. Ниже будут приведены некоторые практические рекомендации. Это совсем не заповеди. Наверняка существуют веские причины для того, чтобы нарушить любое из этих правил.

- Если вы пишете короткий пример кода, который может быть перегружен обработкой ошибок, это, вероятно, отличная возможность использовать

unwrap(будь-тоResult::unwrap,Option::unwrapилиOption::expect). Те, для кого предназначен пример, должны осознавать, что необходимо реализовать надлежащую обработку ошибок. (Если нет, отправляйте их сюда!) - Если вы пишете одноразовую программу, также не зазорно использовать

unwrap. Но будьте внимательны: если ваш код попадет в чужие руки, не удивляйтесь, если кто-то будет расстроен из-за скудных сообщений об ошибках! - Если вы пишете одноразовый код, но вам все-равно стыдно из-за использования

unwrap, воспользуйтесь либоStringв качестве типа ошибки, либоBox<Error + Send + Sync>(из-задоступных реализаций From.) - В остальных случаях, определяйте свои собственные типы ошибок с соответствующими реализациями

FromиError, делая использованиеtry!более удобным. - Если вы пишете библиотеку и ваш код может выдавать ошибки, определите ваш собственный тип ошибки и реализуйте типаж

std::error::Error. Там, где это уместно, реализуйтеFrom, чтобы вам и вашим пользователям было легче с ними работать. (Из-за правил когерентности в Rust, пользователи вашей библиотеки не смогут реализоватьFromдля ваших ошибок, поэтому это должна сделать ваша библиотека.) - Изучите комбинаторы, определенные для

OptionиResult. Писать код, пользуясь только ними может быть немного утомительно, но я лично нашел для себя хороший баланс между использованиемtry!и комбинаторами (and_then,mapиunwrap_or— мои любимые).

Эта статья была подготовлена в рамках перевода на русский язык официального руководства «The Rust Programming Language». Переводы остальных глав этой книги можно найти здесь. Так же, если у вас есть любые вопросы, связанные с Rust, вы можете задать их в чате русскоязычного сообщества Rust.

Перевод | Автор оригинала: Stefan Baumgartner

Я начал читать университетские лекции по Rust, а также проводить семинары и тренинги. Одной из частей, которая превратилась из пары слайдов в полноценный сеанс, было все, что касалось обработки ошибок в Rust, поскольку это невероятно хорошо!

Это не только помогает сделать невозможные состояния невозможными, но и содержит так много деталей, что обработка ошибок — как и все в Rust — становится очень эргономичной и простой для чтения и использования.

Делаем невозможные состояния невозможными

В Rust нет таких вещей, как undefined или null, и у вас нет исключений, как вы знаете из языков программирования, таких как Java или C#. Вместо этого вы используете встроенные перечисления для моделирования состояния:

- Option для привязок, которые могут не иметь значения (например, Some(x) или None)

- Result<T, E> для результатов операций, которые могут привести к ошибке (например, Ok(val) vs Err(error))

Разница между ними очень тонкая и во многом зависит от семантики вашего кода. Однако способ работы обоих перечислений очень похож. На мой взгляд, наиболее важным является то, что оба типа просят вас разобраться с ними. Либо явно обрабатывая все состояния, либо явно игнорируя их.

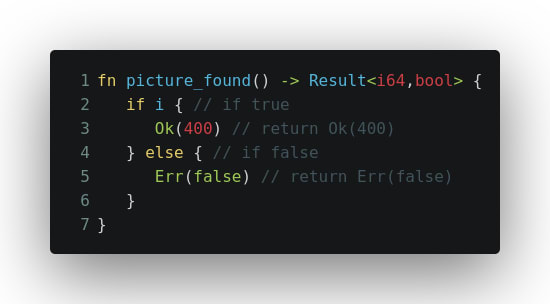

В этой статье я хочу сосредоточиться на Result<T, E>, поскольку он действительно содержит ошибки.

Result<T, E> — это перечисление с двумя вариантами:

enum Result<T, E> {

Ok(T),

Err(E),

}

T, E являются дженериками. T может быть любым значением, E может быть любой ошибкой. Два варианта Ok и Err доступны во всем мире.

Используйте Result<T, E>, когда у вас есть что-то, что может пойти не так. Ожидается, что операция будет успешной, но могут быть случаи, когда это не удается. Когда у вас есть значение Result, вы можете сделать следующее:

- Разберитесь с государствами!

- Игнорируй это

- Паника!

- Используйте запасные варианты

- Распространять ошибки

Давайте подробно рассмотрим, что я имею в виду.

Обработка состояния ошибки

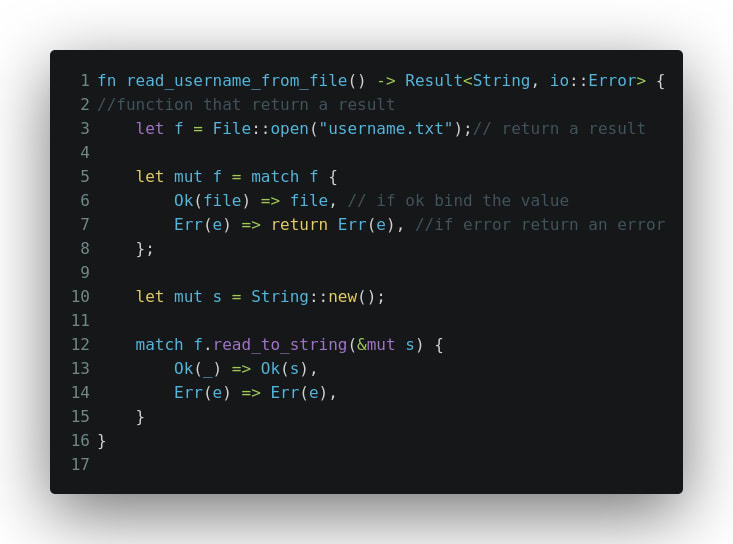

Напишем небольшой фрагмент, в котором мы хотим прочитать строку из файла. Это требует от нас

- Прочтите файл

- Прочтите строку из этого файла.

Обе операции могут вызвать ошибку std::io::Error, потому что может произойти что-то непредвиденное (файл не существует, его нельзя прочитать и т.д.). Таким образом, функция, которую мы пишем, может возвращать либо String, либо io::Error.

use std::io;

use std::fs::File;

fn read_username_from_file(path: &str) -> Result<String, io::Error> {

let f = File::open(path);

/* 1 */

let mut f = match f {

Ok(file) => file,

Err(e) => return Err(e),

};

let mut s = String::new();

/* 2 */

match f.read_to_string(&mut s) {

Ok(_) => Ok(s),

Err(err) => Err(err),

}

}

Вот что происходит:

- Когда мы открываем файл по пути, он либо может вернуть дескриптор файла для работы с Ok(файл), либо вызывает ошибку Err(e). При использовании match f мы вынуждены иметь дело с двумя возможными состояниями. Либо мы назначаем дескриптор файла f (обратите внимание на затенение f), либо возвращаемся из функции, возвращая ошибку. Оператор return здесь важен, поскольку мы хотим выйти из функции.

- Затем мы хотим прочитать содержимое только что созданной строки s. Он снова может либо завершиться успешно, либо выдать ошибку. Функция f.read_to_string возвращает длину прочитанных байтов, поэтому мы можем спокойно игнорировать значение и вернуть Ok(s) с прочитанной строкой. В противном случае мы просто возвращаем ту же ошибку. Обратите внимание, что я не ставил точку с запятой в конце выражения соответствия. Поскольку это выражение, это то, что мы возвращаем из функции в этот момент.

Это может показаться очень многословным (это…), но вы видите два очень важных аспекта обработки ошибок:

- В обоих случаях ожидается, что вы будете иметь дело с двумя возможными состояниями. Вы не можете продолжить, если ничего не сделаете

- Такие функции, как затенение (привязка значения к существующему имени) и выражения, позволяют легко читать и использовать даже подробный код.

Операцию, которую мы только что сделали, часто называют разворачиванием. Потому что вы разворачиваете значение, заключенное внутри перечисления.

Кстати о разворачивании…

Игнорировать ошибки

Если вы абсолютно уверены, что ваша программа не потерпит неудачу, вы можете просто .unwrap() свои значения, используя встроенные функции:

fn read_username_from_file(path: &str) -> Result<String, io::Error> {

let mut f = File::open(path).unwrap(); /* 1 */

let mut s = String::new();

f.read_to_string(&mut s).unwrap(); /* 1 */

Ok(s) /* 2 */

}

Вот что происходит:

- Во всех случаях, которые могут вызвать ошибку, мы вызываем unwrap(), чтобы получить значение

- Оборачиваем результат в вариант Ok, который возвращаем. Мы могли бы просто вернуть s и оставить Result<T, E> в сигнатуре нашей функции. Мы сохраняем его, потому что снова используем его в других примерах.

Сама функция unwrap() очень похожа на то, что мы делали на первом шаге, когда мы работали со всеми состояниями:

// result.rs

impl<T, E: fmt::Debug> Result<T, E> {

// ...

pub fn unwrap(&self) -> T {

match self {

Ok(t) => t,

Err(e) => unwrap_failed("called `Result::unwrap()` on an `Err` value", &e),

}

}

// ...

}

unwrap_failed — это ярлык к панике! макрос. Это означает, что если вы используете .unwrap() и не получите успешного результата, ваше программное обеспечение выйдет из строя.

Вы можете спросить себя: чем это отличается от ошибок, которые просто приводят к сбою программного обеспечения на других языках программирования? Ответ прост: вы должны четко заявить об этом. Rust требует, чтобы вы что-то делали, даже если он явно позволяет паниковать.

Существует множество различных функций .unwrap_, которые можно использовать в различных ситуациях. Мы рассмотрим один или два из них дальше.

Паника!

Говоря о панике, вы также можете паниковать своим собственным паническим сообщением:

fn read_username_from_file(path: &str) -> Result<String, io::Error> {

let mut f = File::open(path).expect("Error opening file");

let mut s = String::new();

f.read_to_string(&mut s).unwrap("Error reading file to string");

Ok(s)

}

То, что делает .expect (…), очень похоже на unwrap()

impl<T, E: fmt::Debug> Result<T, E> {

// ...

pub fn expect(self, msg: &str) -> T {

match self {

Ok(t) => t,

Err(e) => unwrap_failed(msg, &e),

}

}

}

Но у вас в руках свои панические сообщения, которые могут вам понравиться!

Но даже если мы всегда будем откровенны, мы можем захотеть, чтобы наше программное обеспечение не паниковало и не падало всякий раз, когда мы сталкиваемся с ошибкой. Возможно, мы захотим сделать что-нибудь полезное, например, предоставить запасные варианты или… ну… собственноручно обработать ошибки.

Резервные значения

Rust имеет возможность использовать значения по умолчанию в своих перечислениях Result (и Option).

fn read_username_from_file(path: &str) -> Result<String, io::Error> {

let mut f = File::open(path).expect("Error opening file");

let mut s = String::new();

f.read_to_string(&mut s).unwrap_or("admin"); /* 1 */

Ok(s)

}

- «admin» может быть не лучшим вариантом для имени пользователя, но идею вы поняли. Вместо сбоя мы возвращаем значение по умолчанию в случае результата ошибки. Метод .unwrap_or_else принимает закрытие для более сложных значений по умолчанию.

Так-то лучше! Тем не менее, то, что мы до сих пор узнали, — это компромисс между слишком подробным описанием или допуском явных сбоев или, возможно, наличием резервных значений. Но можем ли мы получить и то, и другое? Краткий код и безопасность от ошибок? Мы можем!

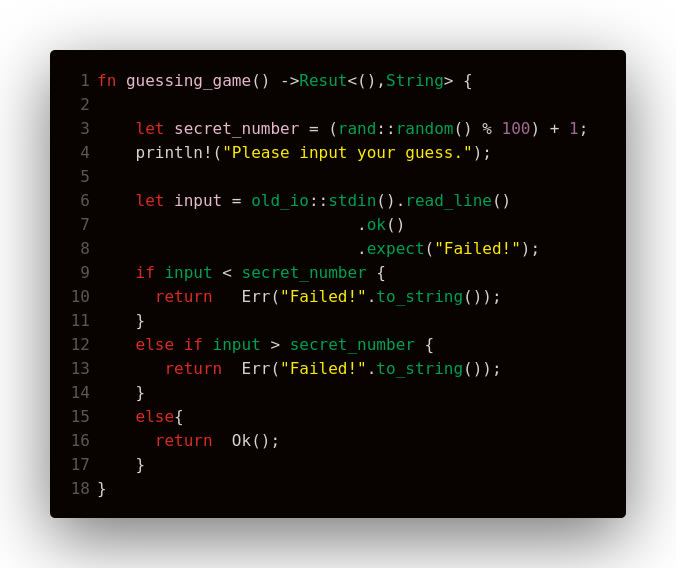

Распространение ошибки

Одна из функций, которые мне больше всего нравятся в типах результатов Rust, — это возможность распространения ошибки. Обе функции, которые могут вызвать ошибку, имеют один и тот же тип ошибки: io::Error. Мы можем использовать оператор вопросительного знака после каждой операции, чтобы писать код для счастливого пути (только успешные результаты) и возвращать результаты ошибок, если что-то пойдет не так:

fn read_username_from_file(path: &str) -> Result<String, io::Error> {

let mut f = File::open(path)?;

let mut s = String::new();

f.read_to_string(&mut s)?;

Ok(s)

}

В этом фрагменте f — обработчик файла, f.read_to_string сохраняет в s. Если что-то пойдет не так, мы вернемся из функции с Err(io::Error). Краткий код, но мы имеем дело с ошибкой на один уровень выше:

fn main() {

match read_username_from_file("user.txt") {

Ok(username) => println!("Welcome {}", username),

Err(err) => eprintln!("Whoopsie! {}", err)

};

}

Что в этом хорошего?

- Мы по-прежнему недвусмысленны, мы должны что-то делать! Вы все еще можете найти все места, где могут произойти ошибки!

- Мы можем писать краткий код, как если бы ошибок не было. Ошибки еще предстоит исправить! Либо от нас, либо от пользователей нашей функции.

Оператор вопросительного знака также работает с Option, это также позволяет создать действительно красивый и элегантный код!

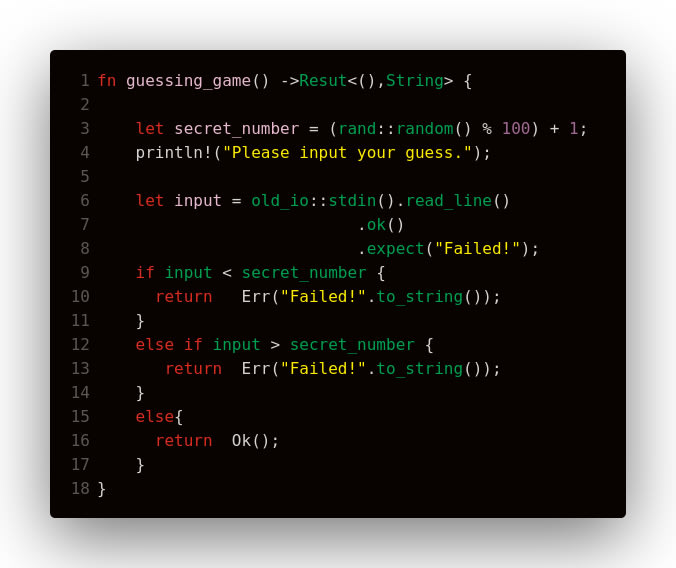

Распространение различных ошибок

Проблема в том, что подобные методы работают только при одинаковом типе ошибок. Если у нас есть два разных типа ошибок, мы должны проявить творческий подход. Посмотрите на эту слегка измененную функцию, в которой мы открываем и читаем файлы, а затем анализируем прочитанное содержимое в u64

fn read_number_from_file(filename: &str) -> Result<u64, ???> {

let mut file = File::open(filename)?; /* 1 */

let mut buffer = String::new();

file.read_to_string(&mut buffer)?; /* 1 */

let parsed: u64 = buffer.trim().parse()?; /* 2 */

Ok(parsed)

}

- Эти две точки могут вызвать io::Error, как мы знаем из предыдущих примеров.

- Однако эта операция может вызвать ошибку ParseIntError.

Проблема в том, что мы не знаем, какую ошибку получаем во время компиляции. Это полностью зависит от запуска нашего кода. Мы можем обрабатывать каждую ошибку с помощью выражений сопоставления и возвращать собственный тип ошибки. Что верно, но снова делает наш код многословным. Или мы готовимся к «вещам, которые происходят во время выполнения»!

Ознакомьтесь с нашей слегка измененной функцией

use std::error;

fn read_number_from_file(filename: &str) -> Result<u64, Box<dyn error::Error>> {

let mut file = File::open(filename)?; /* 1 */

let mut buffer = String::new();

file.read_to_string(&mut buffer)?; /* 1 */

let parsed: u64 = buffer.trim().parse()?; /* 2 */

Ok(parsed)

}

Вот что происходит:

- Вместо того, чтобы возвращать реализацию ошибки, мы сообщаем Rust, что идет что-то, реализующее трэйту ошибки Error.

- Поскольку мы не знаем, что это может быть во время компиляции, мы должны сделать его типажным объектом: dyn std::error::Error.

- А поскольку мы не знаем, насколько это будет большим, мы упаковываем его в Box. Умный указатель, указывающий на данные, которые в конечном итоге будут в куче

Box включает динамическую отправку в Rust: возможность динамически вызывать функцию, которая неизвестна во время компиляции. Для этого Rust представляет виртуальную таблицу, в которой хранятся указатели на фактические реализации. Во время выполнения мы используем эти указатели для вызова соответствующих реализаций функций.

И теперь наш код снова лаконичен, и нашим пользователям приходится иметь дело с возможной ошибкой.

Первый вопрос, который я задаю, когда показываю это людям на моих курсах: но можем ли мы в конечном итоге проверить, какой тип ошибки произошел? Мы можем! Метод downcast_ref() позволяет нам вернуться к исходному типу.

fn main() {

match read_number_from_file("number.txt") {

Ok(v) => println!("Your number is {}", v),

Err(err) => {

if let Some(io_err) = err.downcast_ref::<std::io::Error>() {

eprintln!("Error during IO! {}", io_err)

} else if let Some(pars_err) = err.downcast_ref::<ParseIntError>() {

eprintln!("Error during parsing {}", pars_err)

}

}

};

}

Отлично!

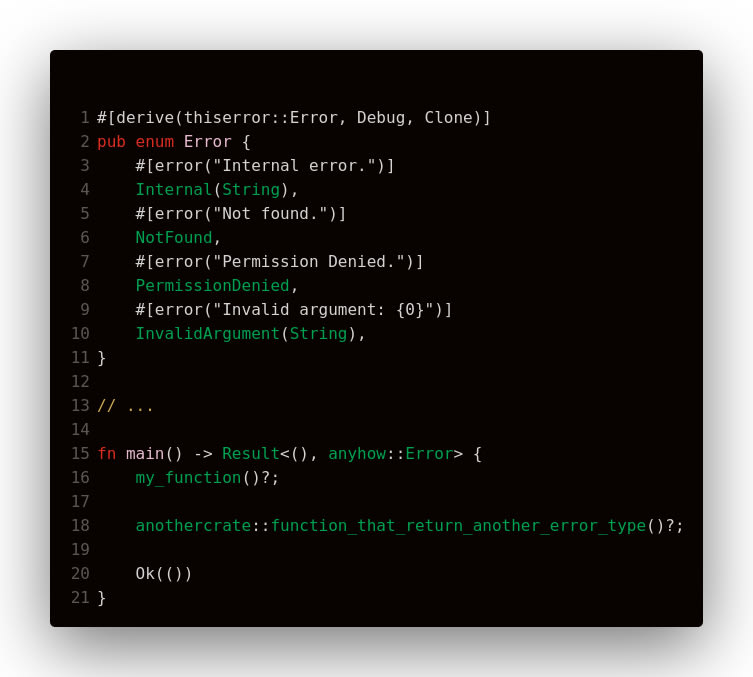

Пользовательские ошибки

Он становится еще лучше и гибче, если вы хотите создавать собственные ошибки для своих операций. Чтобы использовать настраиваемые ошибки, ваши структуры ошибок должны реализовывать трэйту std::error::Error. Это может быть классическая структура, кортежная структура или даже единичная структура.

Вам не нужно реализовывать какие-либо функции std::error::Error, но вам нужно реализовать как трейт Debug, так и свойство Display. Причина в том, что ошибки хотят где-то печатать. Вот как выглядит пример:

#[derive(Debug)] /* 1 */

pub struct ParseArgumentsError(String); /* 2 */

impl std::error::Error for ParseArgumentsError {} /* 3 */

/* 4 */

impl Display for ParseArgumentsError {

fn fmt(&self, f: &mut std::fmt::Formatter<'_>) -> std::fmt::Result {

write!(f, "{}", self.0)

}

}

- Мы выводим трэйту Debug.

- Наша ParseArgumentsError — это структура кортежа с одним элементом: настраиваемое сообщение.

- Реализуем std::error::Error для ParseArgumentsError. Больше ничего реализовывать не нужно

- Мы реализуем Display, где выводим единственный элемент нашего кортежа.

И это все!

Anyhow…

Поскольку многие вещи, которые вы только что выучили, очень распространены, конечно, существуют крэйти, которые абстрагируют большую часть из них. Фантастический крэйт Anyhow Crate — один из них, который дает вам возможность обрабатывать ошибки на основе объектов с помощью удобных макросов и типов.

Нижняя линия

Это очень быстрое руководство по обработке ошибок в Rust. Конечно, это еще не все, но это должно помочь вам начать! Это также моя первая техническая статья по Rust, и я надеюсь, что ее будет еще много. Дайте мне знать, если вам это понравилось, и если вы обнаружите какие-либо… ха-ха… ошибки (ба-дум-ц 🥁), я просто напишу твит.

Search code, repositories, users, issues, pull requests…

Provide feedback

Saved searches

Use saved searches to filter your results more quickly

Sign up

- 8550 words

- 43 min

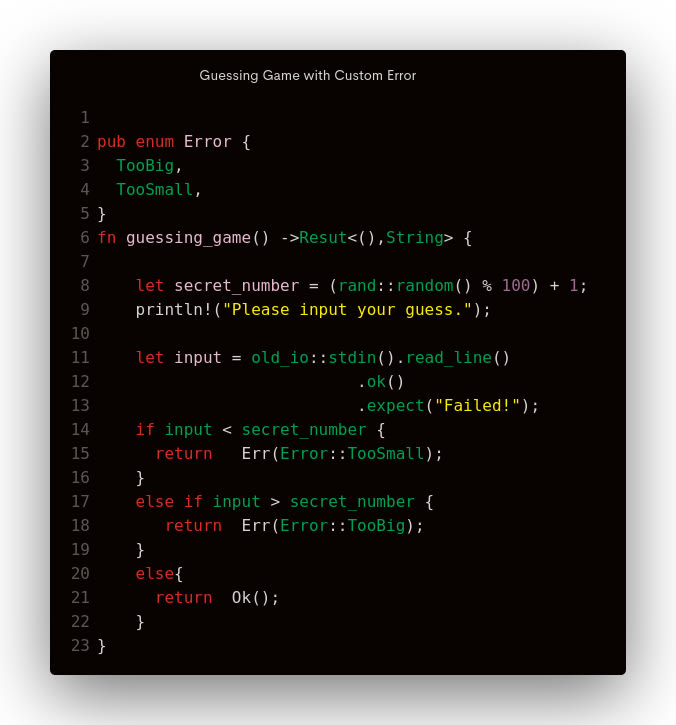

This article is a sample from Zero To Production In Rust, a hands-on introduction to backend development in Rust.

You can get a copy of the book at zero2prod.com.

TL;DR

To send a confirmation email you have to stitch together multiple operations: validation of user input, email dispatch, various database queries.

They all have one thing in common: they may fail.

In Chapter 6 we discussed the building blocks of error handling in Rust — Result and the ? operator.

We left many questions unanswered: how do errors fit within the broader architecture of our application? What does a good error look like? Who are errors for? Should we use a library? Which one?

An in-depth analysis of error handling patterns in Rust will be the sole focus of this chapter.

Chapter 8

- What Is The Purpose Of Errors?

- Internal Errors

- Enable The Caller To React

- Help An Operator To Troubleshoot

- Errors At The Edge

- Help A User To Troubleshoot

- Summary

- Internal Errors

- Error Reporting For Operators

- Keeping Track Of The Error Root Cause

- The

ErrorTrait- Trait Objects

Error::source

- Errors For Control Flow

- Layering

- Modelling Errors as Enums

- The Error Type Is Not Enough

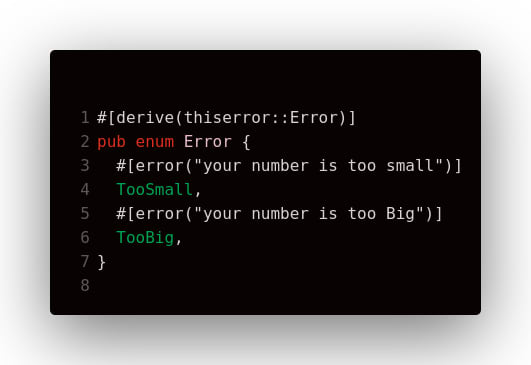

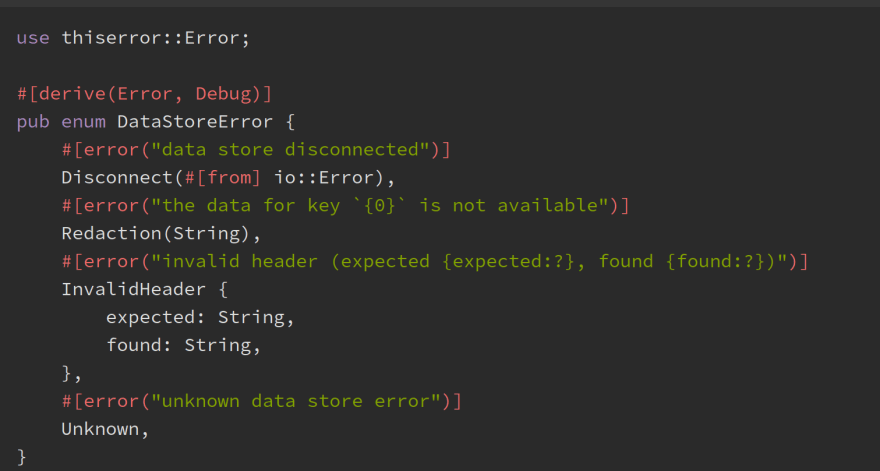

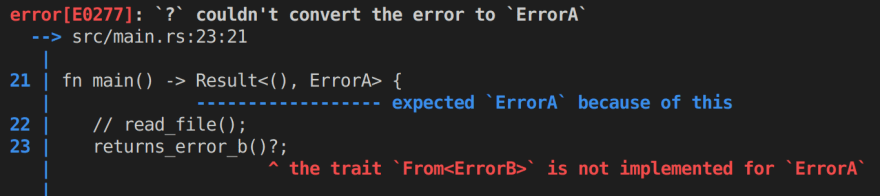

- Removing The Boilerplate With

thiserror

- Avoid «Ball Of Mud» Error Enums

- Using

anyhowAs Opaque Error Type anyhowOrthiserror?

- Using

- Who Should Log Errors?

- Summary

What Is The Purpose Of Errors?

Let’s start with an example:

//! src/routes/subscriptions.rs

// [...]

pub async fn store_token(

transaction: &mut Transaction<'_, Postgres>,

subscriber_id: Uuid,

subscription_token: &str,

) -> Result<(), sqlx::Error> {

sqlx::query!(

r#"

INSERT INTO subscription_tokens (subscription_token, subscriber_id)

VALUES ($1, $2)

"#,

subscription_token,

subscriber_id

)

.execute(transaction)

.await

.map_err(|e| {

tracing::error!("Failed to execute query: {:?}", e);

e

})?;

Ok(())

}

We are trying to insert a row into the subscription_tokens table in order to store a newly-generated token against a subscriber_id.

execute is a fallible operation: we might have a network issue while talking to the database, the row we are trying to insert might violate some table constraints (e.g. uniqueness of the primary key), etc.

Internal Errors

Enable The Caller To React

The caller of execute most likely wants to be informed if a failure occurs — they need to react accordingly, e.g. retry the query or propagate the failure upstream using ?, as in our example.

Rust leverages the type system to communicate that an operation may not succeed: the return type of execute is Result, an enum.

pub enum Result<Success, Error> {

Ok(Success),

Err(Error)

}

The caller is then forced by the compiler to express how they plan to handle both scenarios — success and failure.

If our only goal was to communicate to the caller that an error happened, we could use a simpler definition for Result:

pub enum ResultSignal<Success> {

Ok(Success),

Err

}

There would be no need for a generic Error type — we could just check that execute returned the Err variant, e.g.

let outcome = sqlx::query!(/* ... */)

.execute(transaction)

.await;

if outcome == ResultSignal::Err {

// Do something if it failed

}

This works if there is only one failure mode.

Truth is, operations can fail in multiple ways and we might want to react differently depending on what happened.

Let’s look at the skeleton of sqlx::Error, the error type for execute:

//! sqlx-core/src/error.rs

pub enum Error {

Configuration(/* */),

Database(/* */),

Io(/* */),

Tls(/* */),

Protocol(/* */),

RowNotFound,

TypeNotFound {/* */},

ColumnIndexOutOfBounds {/* */},

ColumnNotFound(/* */),

ColumnDecode {/* */},

Decode(/* */),

PoolTimedOut,

PoolClosed,

WorkerCrashed,

Migrate(/* */),

}

Quite a list, ain’t it?

sqlx::Error is implemented as an enum to allow users to match on the returned error and behave differently depending on the underlying failure mode. For example, you might want to retry a PoolTimedOut while you will probably give up on a ColumnNotFound.

Help An Operator To Troubleshoot

What if an operation has a single failure mode — should we just use () as error type?

Err(()) might be enough for the caller to determine what to do — e.g. return a 500 Internal Server Error to the user.

But control flow is not the only purpose of errors in an application.

We expect errors to carry enough context about the failure to produce a report for an operator (e.g. the developer) that contains enough details to go and troubleshoot the issue.

What do we mean by report?

In a backend API like ours it will usually be a log event.

In a CLI it could be an error message shown in the terminal when a --verbose flag is used.

The implementation details may vary, the purpose stays the same: help a human understand what is going wrong.

That’s exactly what we are doing in the initial code snippet:

//! src/routes/subscriptions.rs

// [...]

pub async fn store_token(/* */) -> Result<(), sqlx::Error> {

sqlx::query!(/* */)

.execute(transaction)

.await

.map_err(|e| {

tracing::error!("Failed to execute query: {:?}", e);

e

})?;

// [...]

}

If the query fails, we grab the error and emit a log event. We can then go and inspect the error logs when investigating the database issue.

Errors At The Edge

Help A User To Troubleshoot

So far we focused on the internals of our API — functions calling other functions and operators trying to make sense of the mess after it happened.

What about users?

Just like operators, users expect the API to signal when a failure mode is encountered.

What does a user of our API see when store_token fails?

We can find out by looking at the request handler:

//! src/routes/subscriptions.rs

// [...]

pub async fn subscribe(/* */) -> HttpResponse {

// [...]

if store_token(&mut transaction, subscriber_id, &subscription_token)

.await

.is_err()

{

return HttpResponse::InternalServerError().finish();

}

// [...]

}

They receive an HTTP response with no body and a 500 Internal Server Error status code.

The status code fulfills the same purpose of the error type in store_token: it is a machine-parsable piece of information that the caller (e.g. the browser) can use to determine what to do next (e.g. retry the request assuming it’s a transient failure).

What about the human behind the browser? What are we telling them?

Not much, the response body is empty.

That is actually a good implementation: the user should not have to care about the internals of the API they are calling — they have no mental model of it and no way to determine why it is failing. That’s the realm of the operator.

We are omitting those details by design.