Для создания котоматрицы не нужно иметь каких-то особых навыков, все очень и очень просто!

Итак, для создания котоматрицы потребуется:

— фотография с любым смешным животным;

— немного фантазии и юмора.

Как создать котоматрицу:

— берем смешную фотографию;

— накладываем на нее смешной текст и… готово!

Сегодня:

- новые пользователи: 0

- создано котоматриц: 0

Полный список…

— Тузик! Сэнсэй! Посмотри, я правильно грызу тапок?

Кот заполняет все отведенное ему пространство независимо от размеров кота и пространства

О себе: симпатучная…

Мне долго маячить тут в окон квадраты?! Немедля откройте! ПЕРСона не жрата!!!

Официант! Гуляем! Еще пробку шампанского и пару коньячных!

НатУрморД «Окорочок в сухарях» Репин (не найденное)

— Вась, убери морду-то! Птичке же вылететь … некуда!

Неслась Ряба, неслась, но яиц от этого не прибавлялось

По утрам, надев трусы, Подведи скорей часы!

Лапы от ушей ему подавай… А ты когда-нибудь брал мышь в её логове?

Через два часа череп моргнул…

Вспомнил Вася грязь и лужи, Беспризорное житье! Если я вам чистым нужен, Ладно, мойте, ё-моё!

— Слышь, хозяин, мне как мурлыкать — очередями или одиночными? — Ты, Вась, главное, без отдачи постарайся!

… не то, чтобы я боялся но это Васькин район!

А я тут…эм…чтобы зайцев не было..

Хозяин, а может, плитка уже приклеилась?

Закон Архимеда: тело, насильно погруженное в воду, вытесняет впоследствии объем жидкости.. в хозяйские тапки!

А я вот тихий. Какая жалость… Мне «шила в попе» не досталось…

ТЫРЕСКОП

Выдаю Мурку замуж в теплые, надежные руки. Проверю.

Начинаю путь к сердцу!

-Дядечко гаишник! Товарищ дважды генерал! Заберите хоть вы у этого…э-э-экстремала либо права, либо меня!!

Раскинулась Мурка широко!Хозяйка бушует вдали!Она убирается в кухне!Осколки и комья земли…

Ну и гадость придумал же кто-то в этом лучшем из лучших миров…

Граждане прохожие, те, что с доброй рожею, сиротинке к ужину. котлеток бросьте дюжину

Миледи — форменная бестья, на вид пушиста и чиста…

-Вась, не помнишь, как там избавиться от молочницы?

ТольСпят хозяева сном лошадиным. Спит весь дом. Мирно кончился день…

Трех носков не хватает… Пасьянс не сходится!

Мам! Это не я — наследил… ты мне веришь??!

я правильно грызу тапок? — Тузик! Сэнсэй! Посмотри,

|

© 2008-2019 Kotomatrix.ru. При перепечатке фотографий гиперссылка на http://kotomatrix.ru обязательна! Администрация: admin [at] kotomatrix.ru Смайлы: kolobok.us |

Ошибка природы — это явление, которое происходит в природе, исключающее гармоничное функционирование экосистемы. Она возникает из-за сбоя в равновесии между различными компонентами природы, такими как животные, растения, почва, вода и атмосфера.

Основной причиной ошибок природы является вмешательство человека в природные процессы. Нарушение естественных циклов, загрязнение окружающей среды, вырубка лесов и перенаселение — все это приводит к нарушению баланса искусственным образом.

Последствия ошибок природы могут быть катастрофическими. Они включают в себя изменение климата, ухудшение качества воздуха, загрязнение водоемов, сокращение биоразнообразия и потерю экосистем. Эти изменения в природной среде оказывают серьезное влияние на жизнь людей и других организмов на планете.

Существует ряд способов исправления ошибок природы. Важно проводить эффективные меры по регулированию загрязнения и восстановлению экосистем. Процессы регенерации почвы, восстановление лесов и охрана природных резерватов — все эти действия могут помочь восстановить равновесие и сохранить природные ресурсы для будущих поколений. Кроме того, важно обращать внимание на устойчивое потребление и ухаживать за окружающей средой, чтобы минимизировать возникновение новых ошибок природы.

Содержание

- Ошибка природы: причины, последствия, исправления

- Причины возникновения ошибки природы

- Последствия ошибки природы

- Способы исправления ошибки природы

- Вопрос-ответ

- Что такое ошибка природы?

- Какие могут быть причины ошибки природы?

- Какие последствия может иметь ошибка природы?

- Как можно исправить ошибку природы?

- Какие современные технологии помогают в исправлении ошибки природы?

Ошибка природы: причины, последствия, исправления

Определение:

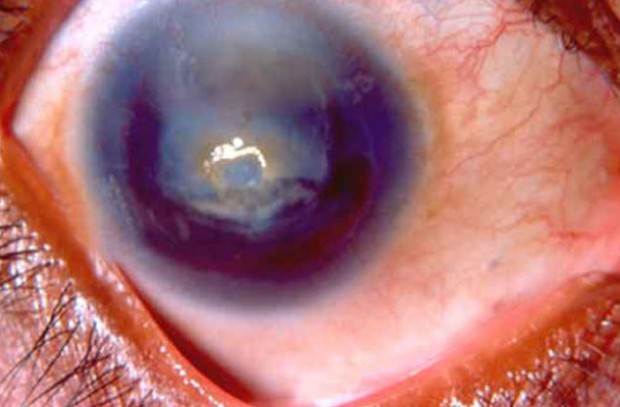

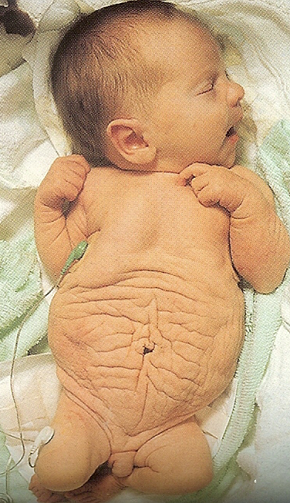

Ошибка природы – это явление, когда в процессе развития организма происходит нарушение нормального функционирования его органов или систем. Ошибка природы может возникнуть как в результате генетических нарушений, так и под воздействием внешних факторов.

Причины ошибки природы:

- Генетические нарушения. Отклонения в генетической информации, передаваемой от родителей к потомству, могут вызвать ошибки природы. Это может быть связано с генетическими мутациями, изменениями в генетической структуре или ошибками в процессе копирования ДНК.

- Воздействие внешних факторов. Ошибка природы может возникнуть из-за негативного воздействия на организм различных факторов окружающей среды, таких как радиация, химические вещества, инфекции, стресс и другие.

Последствия ошибки природы:

- Физические проблемы. Ошибка природы может привести к различным физическим отклонениям, например, косолапости, нарушению зрения или слуха, задержке развития или наличию врожденных пороков сердца.

- Психологические проблемы. Люди с ошибками природы могут столкнуться с психологическими трудностями, такими как низкая самооценка, социальная изоляция, депрессия или тревога.

- Социальные проблемы. Ошибка природы может оказывать влияние на социальное положение человека, влиять на его трудоспособность, возможности в образовании и профессиональной сфере, а также на возможность создания семьи и воспитания потомства.

Исправления ошибки природы:

Исправление ошибки природы может быть достигнуто различными способами, в зависимости от характера и степени нарушения:

- Медикаментозное лечение. В некоторых случаях применение медикаментов может помочь устранить или смягчить симптомы ошибки природы.

- Хирургическое вмешательство. В некоторых случаях оперативное вмешательство может быть необходимо для исправления физических отклонений или врожденных аномалий.

- Терапия и реабилитация. Психологическая или физическая терапия может помочь людям с ошибками природы развивать свои способности и адаптироваться к окружающей среде.

В целом, ошибка природы является сложной проблемой, требующей детального изучения и комплексного подхода к решению. Разработка новых методов диагностики, профилактики и лечения ошибок природы имеет важное значение для улучшения здоровья и качества жизни людей.

Причины возникновения ошибки природы

Ошибка природы — это явление, которое возникает в природе вследствие действия определенных причин. Ошибки природы могут приводить к различным последствиям и иметь негативные для окружающей среды и человека результаты.

Существует несколько основных причин возникновения ошибки природы:

- Естественные причины:

- Естественные катаклизмы, такие как землетрясения, наводнения, смерчи и т.д.

- Экосистемные изменения, вызванные изменением климата или естественным развитием

- Генетические мутации, которые приводят к возникновению новых видов или изменению существующих

- Антропогенные причины:

- Антропогенное воздействие на окружающую среду, такое как загрязнение воздуха, воды, почвы

- Вырубка лесов или разработка шахт и карьеров

- Изменение природной среды под воздействием промышленной или сельскохозяйственной деятельности

- Комбинация естественных и антропогенных причин:

- Климатические изменения, вызванные как естественными факторами, так и антропогенным влиянием

- Усиление последствий естественных катаклизмов из-за антропогенного воздействия на окружающую среду

Ошибки природы могут иметь различные последствия, включая утрату биоразнообразия, разрушение экосистем, изменение климата, перераспределение водных ресурсов и другие отрицательные эффекты на окружающую среду и человечество в целом.

Для исправления ошибок природы необходимо предпринимать соответствующие меры, такие как охрана природных ресурсов, защита и восстановление экосистем, регулирование антропогенного воздействия на окружающую среду и принятие мер по смягчению климатических изменений. Только совместными усилиями общества и государства мы сможем минимизировать ошибки природы и сохранить нашу планету для будущих поколений.

Последствия ошибки природы

Ошибки природы могут иметь серьезные последствия как для окружающей среды, так и для человечества в целом. Ниже приведены некоторые из возможных последствий:

- Экологические проблемы: Ошибки природы могут ухудшить качество воздуха, воды и почвы, а также разрушить экосистемы. Это может привести к вымиранию определенных видов и утрате биоразнообразия, что является серьезным угрозой для экологической устойчивости.

- Потеря ресурсов: Ошибки природы могут привести к неправильному использованию или истощению природных ресурсов. Например, неправильное использование земли может привести к деградации почвы и снижению урожайности.

- Климатические изменения: Ошибки природы, такие как выработка большого количества парниковых газов, могут привести к глобальным климатическим изменениям. Это может привести к экстремальным погодным условиям, усилению стихийных бедствий и росту уровня моря.

- Здоровье человека: Ошибки природы могут негативно сказаться на здоровье человека. Например, загрязнение воздуха может вызывать дыхательные заболевания, а загрязнение воды может привести к распространению инфекционных заболеваний.

Следовательно, исправление ошибок природы является важной задачей. Необходимо принимать меры для ограничения негативных последствий и налаживания устойчивого взаимодействия с окружающей средой.

Способы исправления ошибки природы

Ошибки природы могут иметь серьезные последствия для окружающей нас планеты и всех ее обитателей. Избавиться от этих ошибок представляет собой сложную задачу, но возможно. Вот несколько способов исправления ошибки природы:

-

Осознанное потребление: Одним из основных способов борьбы с ошибками природы является осознанное потребление. Необходимо отказаться от излишнего потребления ресурсов и продуктов, которые наносят вред окружающей среде. При выборе продуктов нужно отдавать предпочтение экологически чистым и устойчивым вариантам. Также важно регулярно изучать информацию о новых технологиях и методах, которые помогут вам сократить свое негативное воздействие на планету.

-

Энергосбережение: Следующим способом исправления ошибки природы является энергосбережение. Это включает в себя использование энергосберегающих устройств и технологий, таких как энергосберегающие лампы, изоляция домов, энергоэффективные бытовые приборы и так далее. Кроме того, необходимо активно избегать нецелесообразного использования энергии и использовать ее эффективнее.

-

Устойчивое земледелие: Отказ от интенсивного использования химических удобрений и пестицидов в земледелии и переход к устойчивым методам может существенно улучшить состояние почвы и водных ресурсов. Применение органического земледелия, компостирование, повышение биологического разнообразия и сохранение почвы помогут восстановлению экосистем и улучшению условий для сельского хозяйства.

-

Охрана природы: Защита природы и сохранение ее биологического разнообразия является еще одним важным способом исправления ошибки природы. Это включает создание заповедников и национальных парков, охрану водных ресурсов, охрану редких и исчезающих видов и многое другое. Организации и государственные структуры играют важную роль в этом процессе и должны принимать активное участие в охране природы и ее ресурсов.

Способы исправления ошибки природы не являются исчерпывающими, но эти изложенные выше методы могут быть важным шагом в направлении сохранения окружающей среды и будущего нашей планеты. Каждое действие, направленное на устранение ошибок природы, имеет значение и может сделать важный вклад в нашу общую благосостояние. Необходимо действовать сегодня, чтобы предотвратить еще большие проблемы в будущем.

Вопрос-ответ

Что такое ошибка природы?

Ошибка природы — это генетическое или развитие патологическое состояние, возникающее в результате неправильной работы генов или других факторов во время эмбрионального развития. Она может проявляться в различных формах и степенях тяжести.

Какие могут быть причины ошибки природы?

Причинами ошибки природы могут быть генетические мутации, влияние внешних факторов на развитие эмбриона, нарушения в питании и образе жизни матери во время беременности, воздействие токсичных веществ и радиации. Также ошибки природы могут быть вызваны комбинацией нескольких факторов.

Какие последствия может иметь ошибка природы?

Последствия ошибки природы могут быть различными и зависят от конкретного случая. Это могут быть физические и психические отклонения, задержка в развитии, недостаток или избыток органов или тканей, нарушения иммунной системы и многое другое. Также ошибки природы могут привести к снижению жизненного качества и продолжительности.

Как можно исправить ошибку природы?

Исправление ошибки природы может быть сложным и требовать множества мер и медицинских вмешательств. В зависимости от конкретной ситуации, может потребоваться хирургическое вмешательство, лекарственная терапия, реабилитация и физическая терапия, психологическая поддержка и обучение адаптивным навыкам. Однако нередко ошибки природы являются неизлечимыми и требуют всестороннего ухода и поддержки.

Какие современные технологии помогают в исправлении ошибки природы?

Современные технологии и медицинский прогресс сделали значительный вклад в исправление ошибок природы. Это включает разработку новых методов генной терапии, использование технологий репродуктивной медицины, например, искусственного оплодотворения, а также развитие робототехники и протезирования. Однако не все ошибки природы могут быть исправлены полностью, и важно помнить, что каждый случай требует индивидуального подхода.

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

For the claim that something is good or right because it is natural (or bad or wrong because it is unnatural), see Appeal to nature.

In philosophical ethics, the naturalistic fallacy is the claim that any reductive explanation of good, in terms of natural properties such as pleasant or desirable, is false. The term was introduced by British philosopher G. E. Moore in his 1903 book Principia Ethica.[1]

Moore’s naturalistic fallacy is closely related to the is–ought problem, which comes from David Hume’s A Treatise of Human Nature (1738–40). However, unlike Hume’s view of the is–ought problem, Moore (and other proponents of ethical non-naturalism) did not consider the naturalistic fallacy to be at odds with moral realism.

The naturalistic fallacy should not be confused with the appeal to nature, which is exemplified by forms of reasoning such as «Something is natural; therefore, it is morally acceptable» or «This property is unnatural; therefore, this property is undesirable.» Such inferences are common in discussions of medicine, sexuality, environmentalism, gender roles, race, and carnism.

Different common uses[edit]

The is–ought problem[edit]

The term naturalistic fallacy is sometimes used to describe the deduction of an ought from an is (the is–ought problem).[2] This usually takes the form of saying that If people do something (e.g., eat three times a day, smoke cigarettes, dress warmly in cold weather), then people ought to do that thing. It becomes a naturalistic fallacy when the is–ought problem («People eat three times a day, so it is morally good for people to eat three times a day») is justified by claiming that whatever practice exists is a natural one («because eating three times a day is pleasant and desirable»).

In using his categorical imperative, Kant deduced that experience was necessary for its application. But experience on its own or the imperative on its own could not possibly identify an act as being moral or immoral. We can have no certain knowledge of morality from them, being incapable of deducing how things ought to be from the fact that they happen to be arranged in a particular manner in experience.

Bentham, in discussing the relations of law and morality, found that when people discuss problems and issues they talk about how they wish it would be, instead of how it actually is. This can be seen in discussions of natural law and positive law. Bentham criticized natural law theory because in his view it was a naturalistic fallacy, claiming that it described how things ought to be instead of how things are.

Moore’s discussion[edit]

The title page of Principia Ethica

According to G. E. Moore’s Principia Ethica, when philosophers try to define good reductively, in terms of natural properties like pleasant or desirable, they are committing the naturalistic fallacy.

…the assumption that because some quality or combination of qualities invariably and necessarily accompanies the quality of goodness, or is invariably and necessarily accompanied by it, or both, this quality or combination of qualities is identical with goodness. If, for example, it is believed that whatever is pleasant is and must be good, or that whatever is good is and must be pleasant, or both, it is committing the naturalistic fallacy to infer from this that goodness and pleasantness are one and the same quality. The naturalistic fallacy is the assumption that because the words ‘good’ and, say, ‘pleasant’ necessarily describe the same objects, they must attribute the same quality to them.[3]

In defense of ethical non-naturalism, Moore’s argument is concerned with the semantic and metaphysical underpinnings of ethics. In general, opponents of ethical naturalism reject ethical conclusions drawn from natural facts.

Moore argues that good, in the sense of intrinsic value, is simply ineffable: it cannot be defined because it is not a natural property, being «one of those innumerable objects of thought which are themselves incapable of definition, because they are the ultimate terms by reference to which whatever ‘is’ capable of definition must be defined».[4] On the other hand, ethical naturalists eschew such principles in favor of a more empirically accessible analysis of what it means to be good: for example, in terms of pleasure in the context of hedonism.

That «pleased» does not mean «having the sensation of red», or anything else whatever, does not prevent us from understanding what it does mean. It is enough for us to know that «pleased» does mean «having the sensation of pleasure», and though pleasure is absolutely indefinable, though pleasure is pleasure and nothing else whatever, yet we feel no difficulty in saying that we are pleased. The reason is, of course, that when I say «I am pleased», I do not mean that «I» am the same thing as «having pleasure». And similarly no difficulty need be found in my saying that «pleasure is good» and yet not meaning that «pleasure» is the same thing as «good», that pleasure means good, and that good means pleasure. If I were to imagine that when I said «I am pleased», I meant that I was exactly the same thing as «pleased», I should not indeed call that a naturalistic fallacy, although it would be the same fallacy as I have called naturalistic with reference to Ethics.

In §7, Moore argues that a property is either a complex of simple properties, or else it is irreducibly simple. Complex properties can be defined in terms of their constituent parts but a simple property has no parts. In addition to good and pleasure, Moore suggests that colour qualia are undefined: if one wants to understand yellow, one must see examples of it. It will do no good to read the dictionary and learn that yellow names the colour of egg yolks and ripe lemons, or that yellow names the primary colour between green and orange on the spectrum, or that the perception of yellow is stimulated by electromagnetic radiation with a wavelength of between 570 and 590 nanometers, because yellow is all that and more, by the open question argument.

Bernard Williams called Moore’s use of the term naturalistic fallacy, a «spectacular misnomer», the question being metaphysical, as opposed to rational.[5]

Appeal to nature[edit]

Some people use the phrase, naturalistic fallacy or appeal to nature, in a different sense, to characterize inferences of the form «Something is natural; therefore, it is morally acceptable» or «This property is unnatural; therefore, this property is undesirable.» Such inferences are common in discussions of medicine, homosexuality, environmentalism, and veganism.

The naturalistic fallacy is the idea that what is found in nature is good. It was the basis for social Darwinism, the belief that helping the poor and sick would get in the way of evolution, which depends on the survival of the fittest. Today, biologists denounce the naturalistic fallacy because they want to describe the natural world honestly, without people deriving morals about how we ought to behave (as in: If birds and beasts engage in adultery, infanticide, cannibalism, it must be OK).

Criticism[edit]

Some philosophers reject the naturalistic fallacy and/or suggest solutions for the proposed is–ought problem.

Bound-up functions[edit]

Ralph McInerny suggests that ought is already bound up in is, insofar as the very nature of things have ends/goals within them. For example, a clock is a device used to keep time. When one understands the function of a clock, then a standard of evaluation is implicit in the very description of the clock, i.e., because it is a clock, it ought to keep the time. Thus, if one cannot pick a good clock from a bad clock, then one does not really know what a clock is. In like manner, if one cannot determine good human action from bad, then one does not really know what the human person is.[7][page needed]

Irrationality of anti-naturalistic fallacy[edit]

Certain uses of the naturalistic fallacy refutation (a scheme of reasoning that declares an inference invalid because it incorporates an instance of the naturalistic fallacy) have been criticized as lacking rational bases, and labelled anti-naturalistic fallacy.[8][page needed] For instance, Alex Walter wrote:

- «The naturalistic fallacy and Hume’s ‘law’ are frequently appealed to for the purpose of drawing limits around the scope of scientific inquiry into ethics and morality. These two objections are shown to be without force.»[9]

The refutations from naturalistic fallacy defined as inferring evaluative conclusions from purely factual premises[10] do assert, implicitly, that there is no connection between the facts and the norms (in particular, between the facts and the mental process that led to adoption of the norms).

Effects of putative necessities[edit]

The effect of beliefs about dangers on behaviors intended to protect what is considered valuable is pointed at as an example of total decoupling of ought from is being impossible. A very basic example is that if the value is that rescuing people is good, different beliefs on whether or not there is a human being in a flotsam box leads to different assessments of whether or not it is a moral imperative to salvage said box from the ocean. For wider-ranging examples, if two people share the value that preservation of a civilized humanity is good, and one believes that a certain ethnic group of humans have a population level statistical hereditary predisposition to destroy civilization while the other person does not believe that such is the case, that difference in beliefs about factual matters will make the first person conclude that persecution of said ethnic group is an excusable «necessary evil» while the second person will conclude that it is a totally unjustifiable evil. The same is also applicable to beliefs about individual differences in predispositions, not necessarily ethnic. In a similar way, two people who both think it is evil to keep people working extremely hard in extreme poverty will draw different conclusions on de facto rights (as opposed to purely semantic rights) of property owners depending on whether or not they believe that humans make up justifications for maximizing their profit, one who believes that people do concluding it necessary to persecute property owners to prevent justification of extreme poverty while the other person concludes that it would be evil to persecute property owners. Such instances are mentioned as examples of beliefs about reality having effects on ethical considerations.[11][12]

Inconsistent application[edit]

Some critics of the assumption that is-ought conclusions are fallacies point at observations of people who purport to consider such conclusions as fallacies do not do so consistently. Examples mentioned are that evolutionary psychologists who gripe about «the naturalistic fallacy» do make is-ought conclusions themselves when, for instance, alleging that the notion of the blank slate would lead to totalitarian social engineering or that certain views on sexuality would lead to attempts to convert homosexuals to heterosexuals. Critics point at this as a sign that charges of the naturalistic fallacy are inconsistent rhetorical tactics rather than detection of a fallacy.[13][14]

Universally normative allegations of varied harm[edit]

A criticism of the concept of the naturalistic fallacy is that while «descriptive» statements (used here in the broad sense about statements that purport to be about facts regardless of whether they are true or false, used simply as opposed to normative statements) about specific differences in effects can be inverted depending on values (such as the statement «people X are predisposed to eating babies» being normative against group X only in the context of protecting children while the statement «individual or group X is predisposed to emit greenhouse gases» is normative against individual/group X only in the context of protecting the environment), the statement «individual/group X is predisposed to harm whatever values others have» is universally normative against individual/group X. This refers to individual/group X being «descriptively» alleged to detect what other entities capable of valuing are protecting and then destroying it without individual/group X having any values of its own. For example, in the context of one philosophy advocating child protection considering eating babies the worst evil and advocating industries that emit greenhouse gases to finance a safe short term environment for children while another philosophy considers long term damage to the environment the worst evil and advocates eating babies to reduce overpopulation and with it consumption that emits greenhouse gases, such an individual/group X could be alleged to advocate both eating babies and building autonomous industries to maximize greenhouse gas emissions, making the two otherwise enemy philosophies become allies against individual/group X as a «common enemy». The principle, that of allegations of an individual or group being predisposed to adapt their harm to damage any values including combined harm of apparently opposite values inevitably making normative implications regardless of which the specific values are, is argued to extend to any other situations with any other values as well due to the allegation being of the individual or group adapting their destruction to different values. This is mentioned as an example of at least one type of «descriptive» allegation being bound to make universally normative implications, as well as the allegation not being scientifically self-correcting due to individual or group X being alleged to manipulate others to support their alleged all-destructive agenda which dismisses any scientific criticism of the allegation as «part of the agenda that destroys everything», and that the objection that some values may condemn some specific ways to persecute individual/group X is irrelevant since different values would also have various ways to do things against individuals or groups that they would consider acceptable to do. This is pointed out as a falsifying counterexample to the claim that «no descriptive statement can in itself become normative».[15][16]

See also[edit]

- Appeal to nature

- Evidence-based medicine

- Appeal to novelty

- Appeal to tradition

- Definist fallacy

- Evolution of morality

- Fact–value distinction

- Meta-ethics

- Moralistic fallacy

- Philosophical naturalism

- Norm (philosophy)

- Open-question argument

- Principia Ethica

- The Right and the Good

- Value theory

Notes[edit]

- ^ Moore, G.E. Principia Ethica § 10 ¶ 3

- ^ W. H. Bruening, «Moore on ‘Is-Ought’,» Ethics 81 (January 1971): 143–49.

- ^ Prior, Arthur N. (1949), Chapter 1 of Logic And The Basis Of Ethics, Oxford University Press (ISBN 0-19-824157-7)

- ^ Moore, G.E. Principia Ethica § 10 ¶ 1

- ^ Williams, Bernard Arthur Owen (2006). Ethics and the Limits of Philosophy. Abingdon, Oxfordshire: Taylor & Francis. p. 121. ISBN 978-0-415-39984-5.

- ^ Sailer, Steve (October 30, 2002). «Q&A: Steven Pinker of ‘Blank Slate’«. UPI. Archived from the original on December 5, 2015. Retrieved December 5, 2015.

- ^ McInerny, Ralph (1982). «Chp. 3». Ethica Thomistica. Cua Press.

- ^ Casebeer, W. D., «Natural Ethical Facts: Evolution, Connectionism, and Moral Cognition», Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, (2003)

- ^ Walter, Alex (2006). «The Anti-naturalistic Fallacy: Evolutionary Moral Psychology and the Insistence of Brute Facts». Evolutionary Psychology. 4: 33–48. doi:10.1177/147470490600400102.

- ^

«naturalistic fallacy», TheFreeDictionary. - ^ Susana Nuccetelli, Gary Seay (2011) «Ethical Naturalism: Current Debates»

- ^ Peter Simpson (2001) «Vices, Virtues, and Consequences: Essays in Moral and Political Philosophy»

- ^ Jan Narveson (2002) «Respecting persons in theory and practice: essays on moral and political philosophy»

- ^ H. J. McCloskey (2013) «Meta-Ethics and Normative Ethics»

- ^ Steven Scalet, John Arthur (2016) «Morality and Moral Controversies: Readings in Moral, Social and Political Philosophy»

- ^ N.T. Potter, Mark Timmons (2012) «Morality and Universality: Essays on Ethical Universalizability»

References[edit]

- Moore, George Edward (1903). Principia Ethica. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-334-04040-X.

Further reading[edit]

- Frankena, W. K. (1939). «The Naturalistic Fallacy». Mind. XLVIII (192): 464–77. doi:10.1093/mind/XLVIII.192.464. JSTOR 2250706.

- Curry, Oliver (2006). «Who’s afraid of the naturalistic fallacy?». Evolutionary Psychology. 4: 234–47. doi:10.1177/147470490600400120.

- Walter, Alex (2006). «The anti-naturalistic fallacy: Evolutionary moral psychology and the insistence of brute facts». Evolutionary Psychology. 4: 33–48. doi:10.1177/147470490600400102.

- Wilson, David Sloan; Dietrich, Eric; Clark, Anne B. (2003). «On the inappropriate use of the naturalistic fallacy in evolutionary psychology». Biology and Philosophy. 18 (5): 669–81. doi:10.1023/A:1026380825208. S2CID 30891026.

External links[edit]

- Principia Ethica Archived 2021-04-12 at the Wayback Machine

- Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). «G.E. Moore». Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). «Moral non-naturalism». Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Appeal to Nature entry in The Fallacy Files

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

For the claim that something is good or right because it is natural (or bad or wrong because it is unnatural), see Appeal to nature.

In philosophical ethics, the naturalistic fallacy is the claim that any reductive explanation of good, in terms of natural properties such as pleasant or desirable, is false. The term was introduced by British philosopher G. E. Moore in his 1903 book Principia Ethica.[1]

Moore’s naturalistic fallacy is closely related to the is–ought problem, which comes from David Hume’s A Treatise of Human Nature (1738–40). However, unlike Hume’s view of the is–ought problem, Moore (and other proponents of ethical non-naturalism) did not consider the naturalistic fallacy to be at odds with moral realism.

The naturalistic fallacy should not be confused with the appeal to nature, which is exemplified by forms of reasoning such as «Something is natural; therefore, it is morally acceptable» or «This property is unnatural; therefore, this property is undesirable.» Such inferences are common in discussions of medicine, sexuality, environmentalism, gender roles, race, and carnism.

Different common uses[edit]

The is–ought problem[edit]

The term naturalistic fallacy is sometimes used to describe the deduction of an ought from an is (the is–ought problem).[2] This usually takes the form of saying that If people do something (e.g., eat three times a day, smoke cigarettes, dress warmly in cold weather), then people ought to do that thing. It becomes a naturalistic fallacy when the is–ought problem («People eat three times a day, so it is morally good for people to eat three times a day») is justified by claiming that whatever practice exists is a natural one («because eating three times a day is pleasant and desirable»).

In using his categorical imperative, Kant deduced that experience was necessary for its application. But experience on its own or the imperative on its own could not possibly identify an act as being moral or immoral. We can have no certain knowledge of morality from them, being incapable of deducing how things ought to be from the fact that they happen to be arranged in a particular manner in experience.

Bentham, in discussing the relations of law and morality, found that when people discuss problems and issues they talk about how they wish it would be, instead of how it actually is. This can be seen in discussions of natural law and positive law. Bentham criticized natural law theory because in his view it was a naturalistic fallacy, claiming that it described how things ought to be instead of how things are.

Moore’s discussion[edit]

The title page of Principia Ethica

According to G. E. Moore’s Principia Ethica, when philosophers try to define good reductively, in terms of natural properties like pleasant or desirable, they are committing the naturalistic fallacy.

…the assumption that because some quality or combination of qualities invariably and necessarily accompanies the quality of goodness, or is invariably and necessarily accompanied by it, or both, this quality or combination of qualities is identical with goodness. If, for example, it is believed that whatever is pleasant is and must be good, or that whatever is good is and must be pleasant, or both, it is committing the naturalistic fallacy to infer from this that goodness and pleasantness are one and the same quality. The naturalistic fallacy is the assumption that because the words ‘good’ and, say, ‘pleasant’ necessarily describe the same objects, they must attribute the same quality to them.[3]

In defense of ethical non-naturalism, Moore’s argument is concerned with the semantic and metaphysical underpinnings of ethics. In general, opponents of ethical naturalism reject ethical conclusions drawn from natural facts.

Moore argues that good, in the sense of intrinsic value, is simply ineffable: it cannot be defined because it is not a natural property, being «one of those innumerable objects of thought which are themselves incapable of definition, because they are the ultimate terms by reference to which whatever ‘is’ capable of definition must be defined».[4] On the other hand, ethical naturalists eschew such principles in favor of a more empirically accessible analysis of what it means to be good: for example, in terms of pleasure in the context of hedonism.

That «pleased» does not mean «having the sensation of red», or anything else whatever, does not prevent us from understanding what it does mean. It is enough for us to know that «pleased» does mean «having the sensation of pleasure», and though pleasure is absolutely indefinable, though pleasure is pleasure and nothing else whatever, yet we feel no difficulty in saying that we are pleased. The reason is, of course, that when I say «I am pleased», I do not mean that «I» am the same thing as «having pleasure». And similarly no difficulty need be found in my saying that «pleasure is good» and yet not meaning that «pleasure» is the same thing as «good», that pleasure means good, and that good means pleasure. If I were to imagine that when I said «I am pleased», I meant that I was exactly the same thing as «pleased», I should not indeed call that a naturalistic fallacy, although it would be the same fallacy as I have called naturalistic with reference to Ethics.

In §7, Moore argues that a property is either a complex of simple properties, or else it is irreducibly simple. Complex properties can be defined in terms of their constituent parts but a simple property has no parts. In addition to good and pleasure, Moore suggests that colour qualia are undefined: if one wants to understand yellow, one must see examples of it. It will do no good to read the dictionary and learn that yellow names the colour of egg yolks and ripe lemons, or that yellow names the primary colour between green and orange on the spectrum, or that the perception of yellow is stimulated by electromagnetic radiation with a wavelength of between 570 and 590 nanometers, because yellow is all that and more, by the open question argument.

Bernard Williams called Moore’s use of the term naturalistic fallacy, a «spectacular misnomer», the question being metaphysical, as opposed to rational.[5]

Appeal to nature[edit]

Some people use the phrase, naturalistic fallacy or appeal to nature, in a different sense, to characterize inferences of the form «Something is natural; therefore, it is morally acceptable» or «This property is unnatural; therefore, this property is undesirable.» Such inferences are common in discussions of medicine, homosexuality, environmentalism, and veganism.

The naturalistic fallacy is the idea that what is found in nature is good. It was the basis for social Darwinism, the belief that helping the poor and sick would get in the way of evolution, which depends on the survival of the fittest. Today, biologists denounce the naturalistic fallacy because they want to describe the natural world honestly, without people deriving morals about how we ought to behave (as in: If birds and beasts engage in adultery, infanticide, cannibalism, it must be OK).

Criticism[edit]

Some philosophers reject the naturalistic fallacy and/or suggest solutions for the proposed is–ought problem.

Bound-up functions[edit]

Ralph McInerny suggests that ought is already bound up in is, insofar as the very nature of things have ends/goals within them. For example, a clock is a device used to keep time. When one understands the function of a clock, then a standard of evaluation is implicit in the very description of the clock, i.e., because it is a clock, it ought to keep the time. Thus, if one cannot pick a good clock from a bad clock, then one does not really know what a clock is. In like manner, if one cannot determine good human action from bad, then one does not really know what the human person is.[7][page needed]

Irrationality of anti-naturalistic fallacy[edit]

Certain uses of the naturalistic fallacy refutation (a scheme of reasoning that declares an inference invalid because it incorporates an instance of the naturalistic fallacy) have been criticized as lacking rational bases, and labelled anti-naturalistic fallacy.[8][page needed] For instance, Alex Walter wrote:

- «The naturalistic fallacy and Hume’s ‘law’ are frequently appealed to for the purpose of drawing limits around the scope of scientific inquiry into ethics and morality. These two objections are shown to be without force.»[9]

The refutations from naturalistic fallacy defined as inferring evaluative conclusions from purely factual premises[10] do assert, implicitly, that there is no connection between the facts and the norms (in particular, between the facts and the mental process that led to adoption of the norms).

Effects of putative necessities[edit]

The effect of beliefs about dangers on behaviors intended to protect what is considered valuable is pointed at as an example of total decoupling of ought from is being impossible. A very basic example is that if the value is that rescuing people is good, different beliefs on whether or not there is a human being in a flotsam box leads to different assessments of whether or not it is a moral imperative to salvage said box from the ocean. For wider-ranging examples, if two people share the value that preservation of a civilized humanity is good, and one believes that a certain ethnic group of humans have a population level statistical hereditary predisposition to destroy civilization while the other person does not believe that such is the case, that difference in beliefs about factual matters will make the first person conclude that persecution of said ethnic group is an excusable «necessary evil» while the second person will conclude that it is a totally unjustifiable evil. The same is also applicable to beliefs about individual differences in predispositions, not necessarily ethnic. In a similar way, two people who both think it is evil to keep people working extremely hard in extreme poverty will draw different conclusions on de facto rights (as opposed to purely semantic rights) of property owners depending on whether or not they believe that humans make up justifications for maximizing their profit, one who believes that people do concluding it necessary to persecute property owners to prevent justification of extreme poverty while the other person concludes that it would be evil to persecute property owners. Such instances are mentioned as examples of beliefs about reality having effects on ethical considerations.[11][12]

Inconsistent application[edit]

Some critics of the assumption that is-ought conclusions are fallacies point at observations of people who purport to consider such conclusions as fallacies do not do so consistently. Examples mentioned are that evolutionary psychologists who gripe about «the naturalistic fallacy» do make is-ought conclusions themselves when, for instance, alleging that the notion of the blank slate would lead to totalitarian social engineering or that certain views on sexuality would lead to attempts to convert homosexuals to heterosexuals. Critics point at this as a sign that charges of the naturalistic fallacy are inconsistent rhetorical tactics rather than detection of a fallacy.[13][14]

Universally normative allegations of varied harm[edit]

A criticism of the concept of the naturalistic fallacy is that while «descriptive» statements (used here in the broad sense about statements that purport to be about facts regardless of whether they are true or false, used simply as opposed to normative statements) about specific differences in effects can be inverted depending on values (such as the statement «people X are predisposed to eating babies» being normative against group X only in the context of protecting children while the statement «individual or group X is predisposed to emit greenhouse gases» is normative against individual/group X only in the context of protecting the environment), the statement «individual/group X is predisposed to harm whatever values others have» is universally normative against individual/group X. This refers to individual/group X being «descriptively» alleged to detect what other entities capable of valuing are protecting and then destroying it without individual/group X having any values of its own. For example, in the context of one philosophy advocating child protection considering eating babies the worst evil and advocating industries that emit greenhouse gases to finance a safe short term environment for children while another philosophy considers long term damage to the environment the worst evil and advocates eating babies to reduce overpopulation and with it consumption that emits greenhouse gases, such an individual/group X could be alleged to advocate both eating babies and building autonomous industries to maximize greenhouse gas emissions, making the two otherwise enemy philosophies become allies against individual/group X as a «common enemy». The principle, that of allegations of an individual or group being predisposed to adapt their harm to damage any values including combined harm of apparently opposite values inevitably making normative implications regardless of which the specific values are, is argued to extend to any other situations with any other values as well due to the allegation being of the individual or group adapting their destruction to different values. This is mentioned as an example of at least one type of «descriptive» allegation being bound to make universally normative implications, as well as the allegation not being scientifically self-correcting due to individual or group X being alleged to manipulate others to support their alleged all-destructive agenda which dismisses any scientific criticism of the allegation as «part of the agenda that destroys everything», and that the objection that some values may condemn some specific ways to persecute individual/group X is irrelevant since different values would also have various ways to do things against individuals or groups that they would consider acceptable to do. This is pointed out as a falsifying counterexample to the claim that «no descriptive statement can in itself become normative».[15][16]

See also[edit]

- Appeal to nature

- Evidence-based medicine

- Appeal to novelty

- Appeal to tradition

- Definist fallacy

- Evolution of morality

- Fact–value distinction

- Meta-ethics

- Moralistic fallacy

- Philosophical naturalism

- Norm (philosophy)

- Open-question argument

- Principia Ethica

- The Right and the Good

- Value theory

Notes[edit]

- ^ Moore, G.E. Principia Ethica § 10 ¶ 3

- ^ W. H. Bruening, «Moore on ‘Is-Ought’,» Ethics 81 (January 1971): 143–49.

- ^ Prior, Arthur N. (1949), Chapter 1 of Logic And The Basis Of Ethics, Oxford University Press (ISBN 0-19-824157-7)

- ^ Moore, G.E. Principia Ethica § 10 ¶ 1

- ^ Williams, Bernard Arthur Owen (2006). Ethics and the Limits of Philosophy. Abingdon, Oxfordshire: Taylor & Francis. p. 121. ISBN 978-0-415-39984-5.

- ^ Sailer, Steve (October 30, 2002). «Q&A: Steven Pinker of ‘Blank Slate’«. UPI. Archived from the original on December 5, 2015. Retrieved December 5, 2015.

- ^ McInerny, Ralph (1982). «Chp. 3». Ethica Thomistica. Cua Press.

- ^ Casebeer, W. D., «Natural Ethical Facts: Evolution, Connectionism, and Moral Cognition», Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, (2003)

- ^ Walter, Alex (2006). «The Anti-naturalistic Fallacy: Evolutionary Moral Psychology and the Insistence of Brute Facts». Evolutionary Psychology. 4: 33–48. doi:10.1177/147470490600400102.

- ^

«naturalistic fallacy», TheFreeDictionary. - ^ Susana Nuccetelli, Gary Seay (2011) «Ethical Naturalism: Current Debates»

- ^ Peter Simpson (2001) «Vices, Virtues, and Consequences: Essays in Moral and Political Philosophy»

- ^ Jan Narveson (2002) «Respecting persons in theory and practice: essays on moral and political philosophy»

- ^ H. J. McCloskey (2013) «Meta-Ethics and Normative Ethics»

- ^ Steven Scalet, John Arthur (2016) «Morality and Moral Controversies: Readings in Moral, Social and Political Philosophy»

- ^ N.T. Potter, Mark Timmons (2012) «Morality and Universality: Essays on Ethical Universalizability»

References[edit]

- Moore, George Edward (1903). Principia Ethica. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-334-04040-X.

Further reading[edit]

- Frankena, W. K. (1939). «The Naturalistic Fallacy». Mind. XLVIII (192): 464–77. doi:10.1093/mind/XLVIII.192.464. JSTOR 2250706.

- Curry, Oliver (2006). «Who’s afraid of the naturalistic fallacy?». Evolutionary Psychology. 4: 234–47. doi:10.1177/147470490600400120.

- Walter, Alex (2006). «The anti-naturalistic fallacy: Evolutionary moral psychology and the insistence of brute facts». Evolutionary Psychology. 4: 33–48. doi:10.1177/147470490600400102.

- Wilson, David Sloan; Dietrich, Eric; Clark, Anne B. (2003). «On the inappropriate use of the naturalistic fallacy in evolutionary psychology». Biology and Philosophy. 18 (5): 669–81. doi:10.1023/A:1026380825208. S2CID 30891026.

External links[edit]

- Principia Ethica Archived 2021-04-12 at the Wayback Machine

- Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). «G.E. Moore». Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). «Moral non-naturalism». Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Appeal to Nature entry in The Fallacy Files

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

For the claim that something is good or right because it is natural (or bad or wrong because it is unnatural), see Appeal to nature.

In philosophical ethics, the naturalistic fallacy is the claim that any reductive explanation of good, in terms of natural properties such as pleasant or desirable, is false. The term was introduced by British philosopher G. E. Moore in his 1903 book Principia Ethica.[1]

Moore’s naturalistic fallacy is closely related to the is–ought problem, which comes from David Hume’s A Treatise of Human Nature (1738–40). However, unlike Hume’s view of the is–ought problem, Moore (and other proponents of ethical non-naturalism) did not consider the naturalistic fallacy to be at odds with moral realism.

The naturalistic fallacy should not be confused with the appeal to nature, which is exemplified by forms of reasoning such as «Something is natural; therefore, it is morally acceptable» or «This property is unnatural; therefore, this property is undesirable.» Such inferences are common in discussions of medicine, sexuality, environmentalism, gender roles, race, and carnism.

Different common uses[edit]

The is–ought problem[edit]

The term naturalistic fallacy is sometimes used to describe the deduction of an ought from an is (the is–ought problem).[2] This usually takes the form of saying that If people do something (e.g., eat three times a day, smoke cigarettes, dress warmly in cold weather), then people ought to do that thing. It becomes a naturalistic fallacy when the is–ought problem («People eat three times a day, so it is morally good for people to eat three times a day») is justified by claiming that whatever practice exists is a natural one («because eating three times a day is pleasant and desirable»).

In using his categorical imperative, Kant deduced that experience was necessary for its application. But experience on its own or the imperative on its own could not possibly identify an act as being moral or immoral. We can have no certain knowledge of morality from them, being incapable of deducing how things ought to be from the fact that they happen to be arranged in a particular manner in experience.

Bentham, in discussing the relations of law and morality, found that when people discuss problems and issues they talk about how they wish it would be, instead of how it actually is. This can be seen in discussions of natural law and positive law. Bentham criticized natural law theory because in his view it was a naturalistic fallacy, claiming that it described how things ought to be instead of how things are.

Moore’s discussion[edit]

The title page of Principia Ethica

According to G. E. Moore’s Principia Ethica, when philosophers try to define good reductively, in terms of natural properties like pleasant or desirable, they are committing the naturalistic fallacy.

…the assumption that because some quality or combination of qualities invariably and necessarily accompanies the quality of goodness, or is invariably and necessarily accompanied by it, or both, this quality or combination of qualities is identical with goodness. If, for example, it is believed that whatever is pleasant is and must be good, or that whatever is good is and must be pleasant, or both, it is committing the naturalistic fallacy to infer from this that goodness and pleasantness are one and the same quality. The naturalistic fallacy is the assumption that because the words ‘good’ and, say, ‘pleasant’ necessarily describe the same objects, they must attribute the same quality to them.[3]

In defense of ethical non-naturalism, Moore’s argument is concerned with the semantic and metaphysical underpinnings of ethics. In general, opponents of ethical naturalism reject ethical conclusions drawn from natural facts.

Moore argues that good, in the sense of intrinsic value, is simply ineffable: it cannot be defined because it is not a natural property, being «one of those innumerable objects of thought which are themselves incapable of definition, because they are the ultimate terms by reference to which whatever ‘is’ capable of definition must be defined».[4] On the other hand, ethical naturalists eschew such principles in favor of a more empirically accessible analysis of what it means to be good: for example, in terms of pleasure in the context of hedonism.

That «pleased» does not mean «having the sensation of red», or anything else whatever, does not prevent us from understanding what it does mean. It is enough for us to know that «pleased» does mean «having the sensation of pleasure», and though pleasure is absolutely indefinable, though pleasure is pleasure and nothing else whatever, yet we feel no difficulty in saying that we are pleased. The reason is, of course, that when I say «I am pleased», I do not mean that «I» am the same thing as «having pleasure». And similarly no difficulty need be found in my saying that «pleasure is good» and yet not meaning that «pleasure» is the same thing as «good», that pleasure means good, and that good means pleasure. If I were to imagine that when I said «I am pleased», I meant that I was exactly the same thing as «pleased», I should not indeed call that a naturalistic fallacy, although it would be the same fallacy as I have called naturalistic with reference to Ethics.

In §7, Moore argues that a property is either a complex of simple properties, or else it is irreducibly simple. Complex properties can be defined in terms of their constituent parts but a simple property has no parts. In addition to good and pleasure, Moore suggests that colour qualia are undefined: if one wants to understand yellow, one must see examples of it. It will do no good to read the dictionary and learn that yellow names the colour of egg yolks and ripe lemons, or that yellow names the primary colour between green and orange on the spectrum, or that the perception of yellow is stimulated by electromagnetic radiation with a wavelength of between 570 and 590 nanometers, because yellow is all that and more, by the open question argument.

Bernard Williams called Moore’s use of the term naturalistic fallacy, a «spectacular misnomer», the question being metaphysical, as opposed to rational.[5]

Appeal to nature[edit]

Some people use the phrase, naturalistic fallacy or appeal to nature, in a different sense, to characterize inferences of the form «Something is natural; therefore, it is morally acceptable» or «This property is unnatural; therefore, this property is undesirable.» Such inferences are common in discussions of medicine, homosexuality, environmentalism, and veganism.

The naturalistic fallacy is the idea that what is found in nature is good. It was the basis for social Darwinism, the belief that helping the poor and sick would get in the way of evolution, which depends on the survival of the fittest. Today, biologists denounce the naturalistic fallacy because they want to describe the natural world honestly, without people deriving morals about how we ought to behave (as in: If birds and beasts engage in adultery, infanticide, cannibalism, it must be OK).

Criticism[edit]

Some philosophers reject the naturalistic fallacy and/or suggest solutions for the proposed is–ought problem.

Bound-up functions[edit]

Ralph McInerny suggests that ought is already bound up in is, insofar as the very nature of things have ends/goals within them. For example, a clock is a device used to keep time. When one understands the function of a clock, then a standard of evaluation is implicit in the very description of the clock, i.e., because it is a clock, it ought to keep the time. Thus, if one cannot pick a good clock from a bad clock, then one does not really know what a clock is. In like manner, if one cannot determine good human action from bad, then one does not really know what the human person is.[7][page needed]

Irrationality of anti-naturalistic fallacy[edit]

Certain uses of the naturalistic fallacy refutation (a scheme of reasoning that declares an inference invalid because it incorporates an instance of the naturalistic fallacy) have been criticized as lacking rational bases, and labelled anti-naturalistic fallacy.[8][page needed] For instance, Alex Walter wrote:

- «The naturalistic fallacy and Hume’s ‘law’ are frequently appealed to for the purpose of drawing limits around the scope of scientific inquiry into ethics and morality. These two objections are shown to be without force.»[9]

The refutations from naturalistic fallacy defined as inferring evaluative conclusions from purely factual premises[10] do assert, implicitly, that there is no connection between the facts and the norms (in particular, between the facts and the mental process that led to adoption of the norms).

Effects of putative necessities[edit]

The effect of beliefs about dangers on behaviors intended to protect what is considered valuable is pointed at as an example of total decoupling of ought from is being impossible. A very basic example is that if the value is that rescuing people is good, different beliefs on whether or not there is a human being in a flotsam box leads to different assessments of whether or not it is a moral imperative to salvage said box from the ocean. For wider-ranging examples, if two people share the value that preservation of a civilized humanity is good, and one believes that a certain ethnic group of humans have a population level statistical hereditary predisposition to destroy civilization while the other person does not believe that such is the case, that difference in beliefs about factual matters will make the first person conclude that persecution of said ethnic group is an excusable «necessary evil» while the second person will conclude that it is a totally unjustifiable evil. The same is also applicable to beliefs about individual differences in predispositions, not necessarily ethnic. In a similar way, two people who both think it is evil to keep people working extremely hard in extreme poverty will draw different conclusions on de facto rights (as opposed to purely semantic rights) of property owners depending on whether or not they believe that humans make up justifications for maximizing their profit, one who believes that people do concluding it necessary to persecute property owners to prevent justification of extreme poverty while the other person concludes that it would be evil to persecute property owners. Such instances are mentioned as examples of beliefs about reality having effects on ethical considerations.[11][12]

Inconsistent application[edit]

Some critics of the assumption that is-ought conclusions are fallacies point at observations of people who purport to consider such conclusions as fallacies do not do so consistently. Examples mentioned are that evolutionary psychologists who gripe about «the naturalistic fallacy» do make is-ought conclusions themselves when, for instance, alleging that the notion of the blank slate would lead to totalitarian social engineering or that certain views on sexuality would lead to attempts to convert homosexuals to heterosexuals. Critics point at this as a sign that charges of the naturalistic fallacy are inconsistent rhetorical tactics rather than detection of a fallacy.[13][14]

Universally normative allegations of varied harm[edit]

A criticism of the concept of the naturalistic fallacy is that while «descriptive» statements (used here in the broad sense about statements that purport to be about facts regardless of whether they are true or false, used simply as opposed to normative statements) about specific differences in effects can be inverted depending on values (such as the statement «people X are predisposed to eating babies» being normative against group X only in the context of protecting children while the statement «individual or group X is predisposed to emit greenhouse gases» is normative against individual/group X only in the context of protecting the environment), the statement «individual/group X is predisposed to harm whatever values others have» is universally normative against individual/group X. This refers to individual/group X being «descriptively» alleged to detect what other entities capable of valuing are protecting and then destroying it without individual/group X having any values of its own. For example, in the context of one philosophy advocating child protection considering eating babies the worst evil and advocating industries that emit greenhouse gases to finance a safe short term environment for children while another philosophy considers long term damage to the environment the worst evil and advocates eating babies to reduce overpopulation and with it consumption that emits greenhouse gases, such an individual/group X could be alleged to advocate both eating babies and building autonomous industries to maximize greenhouse gas emissions, making the two otherwise enemy philosophies become allies against individual/group X as a «common enemy». The principle, that of allegations of an individual or group being predisposed to adapt their harm to damage any values including combined harm of apparently opposite values inevitably making normative implications regardless of which the specific values are, is argued to extend to any other situations with any other values as well due to the allegation being of the individual or group adapting their destruction to different values. This is mentioned as an example of at least one type of «descriptive» allegation being bound to make universally normative implications, as well as the allegation not being scientifically self-correcting due to individual or group X being alleged to manipulate others to support their alleged all-destructive agenda which dismisses any scientific criticism of the allegation as «part of the agenda that destroys everything», and that the objection that some values may condemn some specific ways to persecute individual/group X is irrelevant since different values would also have various ways to do things against individuals or groups that they would consider acceptable to do. This is pointed out as a falsifying counterexample to the claim that «no descriptive statement can in itself become normative».[15][16]

See also[edit]

- Appeal to nature

- Evidence-based medicine

- Appeal to novelty

- Appeal to tradition

- Definist fallacy

- Evolution of morality

- Fact–value distinction

- Meta-ethics

- Moralistic fallacy

- Philosophical naturalism

- Norm (philosophy)

- Open-question argument

- Principia Ethica

- The Right and the Good

- Value theory

Notes[edit]

- ^ Moore, G.E. Principia Ethica § 10 ¶ 3

- ^ W. H. Bruening, «Moore on ‘Is-Ought’,» Ethics 81 (January 1971): 143–49.

- ^ Prior, Arthur N. (1949), Chapter 1 of Logic And The Basis Of Ethics, Oxford University Press (ISBN 0-19-824157-7)

- ^ Moore, G.E. Principia Ethica § 10 ¶ 1

- ^ Williams, Bernard Arthur Owen (2006). Ethics and the Limits of Philosophy. Abingdon, Oxfordshire: Taylor & Francis. p. 121. ISBN 978-0-415-39984-5.

- ^ Sailer, Steve (October 30, 2002). «Q&A: Steven Pinker of ‘Blank Slate’«. UPI. Archived from the original on December 5, 2015. Retrieved December 5, 2015.

- ^ McInerny, Ralph (1982). «Chp. 3». Ethica Thomistica. Cua Press.

- ^ Casebeer, W. D., «Natural Ethical Facts: Evolution, Connectionism, and Moral Cognition», Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, (2003)

- ^ Walter, Alex (2006). «The Anti-naturalistic Fallacy: Evolutionary Moral Psychology and the Insistence of Brute Facts». Evolutionary Psychology. 4: 33–48. doi:10.1177/147470490600400102.

- ^

«naturalistic fallacy», TheFreeDictionary. - ^ Susana Nuccetelli, Gary Seay (2011) «Ethical Naturalism: Current Debates»

- ^ Peter Simpson (2001) «Vices, Virtues, and Consequences: Essays in Moral and Political Philosophy»

- ^ Jan Narveson (2002) «Respecting persons in theory and practice: essays on moral and political philosophy»

- ^ H. J. McCloskey (2013) «Meta-Ethics and Normative Ethics»

- ^ Steven Scalet, John Arthur (2016) «Morality and Moral Controversies: Readings in Moral, Social and Political Philosophy»

- ^ N.T. Potter, Mark Timmons (2012) «Morality and Universality: Essays on Ethical Universalizability»

References[edit]

- Moore, George Edward (1903). Principia Ethica. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-334-04040-X.

Further reading[edit]

- Frankena, W. K. (1939). «The Naturalistic Fallacy». Mind. XLVIII (192): 464–77. doi:10.1093/mind/XLVIII.192.464. JSTOR 2250706.

- Curry, Oliver (2006). «Who’s afraid of the naturalistic fallacy?». Evolutionary Psychology. 4: 234–47. doi:10.1177/147470490600400120.

- Walter, Alex (2006). «The anti-naturalistic fallacy: Evolutionary moral psychology and the insistence of brute facts». Evolutionary Psychology. 4: 33–48. doi:10.1177/147470490600400102.

- Wilson, David Sloan; Dietrich, Eric; Clark, Anne B. (2003). «On the inappropriate use of the naturalistic fallacy in evolutionary psychology». Biology and Philosophy. 18 (5): 669–81. doi:10.1023/A:1026380825208. S2CID 30891026.

External links[edit]

- Principia Ethica Archived 2021-04-12 at the Wayback Machine

- Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). «G.E. Moore». Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). «Moral non-naturalism». Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Appeal to Nature entry in The Fallacy Files

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

For the claim that something is good or right because it is natural (or bad or wrong because it is unnatural), see Appeal to nature.

In philosophical ethics, the naturalistic fallacy is the claim that any reductive explanation of good, in terms of natural properties such as pleasant or desirable, is false. The term was introduced by British philosopher G. E. Moore in his 1903 book Principia Ethica.[1]

Moore’s naturalistic fallacy is closely related to the is–ought problem, which comes from David Hume’s A Treatise of Human Nature (1738–40). However, unlike Hume’s view of the is–ought problem, Moore (and other proponents of ethical non-naturalism) did not consider the naturalistic fallacy to be at odds with moral realism.

The naturalistic fallacy should not be confused with the appeal to nature, which is exemplified by forms of reasoning such as «Something is natural; therefore, it is morally acceptable» or «This property is unnatural; therefore, this property is undesirable.» Such inferences are common in discussions of medicine, sexuality, environmentalism, gender roles, race, and carnism.

Different common uses[edit]

The is–ought problem[edit]

The term naturalistic fallacy is sometimes used to describe the deduction of an ought from an is (the is–ought problem).[2] This usually takes the form of saying that If people do something (e.g., eat three times a day, smoke cigarettes, dress warmly in cold weather), then people ought to do that thing. It becomes a naturalistic fallacy when the is–ought problem («People eat three times a day, so it is morally good for people to eat three times a day») is justified by claiming that whatever practice exists is a natural one («because eating three times a day is pleasant and desirable»).

In using his categorical imperative, Kant deduced that experience was necessary for its application. But experience on its own or the imperative on its own could not possibly identify an act as being moral or immoral. We can have no certain knowledge of morality from them, being incapable of deducing how things ought to be from the fact that they happen to be arranged in a particular manner in experience.

Bentham, in discussing the relations of law and morality, found that when people discuss problems and issues they talk about how they wish it would be, instead of how it actually is. This can be seen in discussions of natural law and positive law. Bentham criticized natural law theory because in his view it was a naturalistic fallacy, claiming that it described how things ought to be instead of how things are.

Moore’s discussion[edit]

The title page of Principia Ethica

According to G. E. Moore’s Principia Ethica, when philosophers try to define good reductively, in terms of natural properties like pleasant or desirable, they are committing the naturalistic fallacy.

…the assumption that because some quality or combination of qualities invariably and necessarily accompanies the quality of goodness, or is invariably and necessarily accompanied by it, or both, this quality or combination of qualities is identical with goodness. If, for example, it is believed that whatever is pleasant is and must be good, or that whatever is good is and must be pleasant, or both, it is committing the naturalistic fallacy to infer from this that goodness and pleasantness are one and the same quality. The naturalistic fallacy is the assumption that because the words ‘good’ and, say, ‘pleasant’ necessarily describe the same objects, they must attribute the same quality to them.[3]

In defense of ethical non-naturalism, Moore’s argument is concerned with the semantic and metaphysical underpinnings of ethics. In general, opponents of ethical naturalism reject ethical conclusions drawn from natural facts.

Moore argues that good, in the sense of intrinsic value, is simply ineffable: it cannot be defined because it is not a natural property, being «one of those innumerable objects of thought which are themselves incapable of definition, because they are the ultimate terms by reference to which whatever ‘is’ capable of definition must be defined».[4] On the other hand, ethical naturalists eschew such principles in favor of a more empirically accessible analysis of what it means to be good: for example, in terms of pleasure in the context of hedonism.

That «pleased» does not mean «having the sensation of red», or anything else whatever, does not prevent us from understanding what it does mean. It is enough for us to know that «pleased» does mean «having the sensation of pleasure», and though pleasure is absolutely indefinable, though pleasure is pleasure and nothing else whatever, yet we feel no difficulty in saying that we are pleased. The reason is, of course, that when I say «I am pleased», I do not mean that «I» am the same thing as «having pleasure». And similarly no difficulty need be found in my saying that «pleasure is good» and yet not meaning that «pleasure» is the same thing as «good», that pleasure means good, and that good means pleasure. If I were to imagine that when I said «I am pleased», I meant that I was exactly the same thing as «pleased», I should not indeed call that a naturalistic fallacy, although it would be the same fallacy as I have called naturalistic with reference to Ethics.

In §7, Moore argues that a property is either a complex of simple properties, or else it is irreducibly simple. Complex properties can be defined in terms of their constituent parts but a simple property has no parts. In addition to good and pleasure, Moore suggests that colour qualia are undefined: if one wants to understand yellow, one must see examples of it. It will do no good to read the dictionary and learn that yellow names the colour of egg yolks and ripe lemons, or that yellow names the primary colour between green and orange on the spectrum, or that the perception of yellow is stimulated by electromagnetic radiation with a wavelength of between 570 and 590 nanometers, because yellow is all that and more, by the open question argument.

Bernard Williams called Moore’s use of the term naturalistic fallacy, a «spectacular misnomer», the question being metaphysical, as opposed to rational.[5]

Appeal to nature[edit]

Some people use the phrase, naturalistic fallacy or appeal to nature, in a different sense, to characterize inferences of the form «Something is natural; therefore, it is morally acceptable» or «This property is unnatural; therefore, this property is undesirable.» Such inferences are common in discussions of medicine, homosexuality, environmentalism, and veganism.

The naturalistic fallacy is the idea that what is found in nature is good. It was the basis for social Darwinism, the belief that helping the poor and sick would get in the way of evolution, which depends on the survival of the fittest. Today, biologists denounce the naturalistic fallacy because they want to describe the natural world honestly, without people deriving morals about how we ought to behave (as in: If birds and beasts engage in adultery, infanticide, cannibalism, it must be OK).

Criticism[edit]

Some philosophers reject the naturalistic fallacy and/or suggest solutions for the proposed is–ought problem.

Bound-up functions[edit]

Ralph McInerny suggests that ought is already bound up in is, insofar as the very nature of things have ends/goals within them. For example, a clock is a device used to keep time. When one understands the function of a clock, then a standard of evaluation is implicit in the very description of the clock, i.e., because it is a clock, it ought to keep the time. Thus, if one cannot pick a good clock from a bad clock, then one does not really know what a clock is. In like manner, if one cannot determine good human action from bad, then one does not really know what the human person is.[7][page needed]

Irrationality of anti-naturalistic fallacy[edit]

Certain uses of the naturalistic fallacy refutation (a scheme of reasoning that declares an inference invalid because it incorporates an instance of the naturalistic fallacy) have been criticized as lacking rational bases, and labelled anti-naturalistic fallacy.[8][page needed] For instance, Alex Walter wrote:

- «The naturalistic fallacy and Hume’s ‘law’ are frequently appealed to for the purpose of drawing limits around the scope of scientific inquiry into ethics and morality. These two objections are shown to be without force.»[9]

The refutations from naturalistic fallacy defined as inferring evaluative conclusions from purely factual premises[10] do assert, implicitly, that there is no connection between the facts and the norms (in particular, between the facts and the mental process that led to adoption of the norms).

Effects of putative necessities[edit]

The effect of beliefs about dangers on behaviors intended to protect what is considered valuable is pointed at as an example of total decoupling of ought from is being impossible. A very basic example is that if the value is that rescuing people is good, different beliefs on whether or not there is a human being in a flotsam box leads to different assessments of whether or not it is a moral imperative to salvage said box from the ocean. For wider-ranging examples, if two people share the value that preservation of a civilized humanity is good, and one believes that a certain ethnic group of humans have a population level statistical hereditary predisposition to destroy civilization while the other person does not believe that such is the case, that difference in beliefs about factual matters will make the first person conclude that persecution of said ethnic group is an excusable «necessary evil» while the second person will conclude that it is a totally unjustifiable evil. The same is also applicable to beliefs about individual differences in predispositions, not necessarily ethnic. In a similar way, two people who both think it is evil to keep people working extremely hard in extreme poverty will draw different conclusions on de facto rights (as opposed to purely semantic rights) of property owners depending on whether or not they believe that humans make up justifications for maximizing their profit, one who believes that people do concluding it necessary to persecute property owners to prevent justification of extreme poverty while the other person concludes that it would be evil to persecute property owners. Such instances are mentioned as examples of beliefs about reality having effects on ethical considerations.[11][12]

Inconsistent application[edit]

Some critics of the assumption that is-ought conclusions are fallacies point at observations of people who purport to consider such conclusions as fallacies do not do so consistently. Examples mentioned are that evolutionary psychologists who gripe about «the naturalistic fallacy» do make is-ought conclusions themselves when, for instance, alleging that the notion of the blank slate would lead to totalitarian social engineering or that certain views on sexuality would lead to attempts to convert homosexuals to heterosexuals. Critics point at this as a sign that charges of the naturalistic fallacy are inconsistent rhetorical tactics rather than detection of a fallacy.[13][14]

Universally normative allegations of varied harm[edit]