- Научные ошибки в Коране

- Солнце

- Гром и молнии

- Земля

- Исторические ошибки Корана

- Распятие Христа

- Дева Мария

- Александр Македонский

- Другие исторические ошибки

- Коранический язык и грамматически ошибки

Наши мусульманские друзья верят, что Коран является книгой Господа и что он существует наравне с Господом извечно. Они верят, что Господь ниспосылал его Мухаммеду через архангела Гавриила в различных ситуациях в течение нескольких лет. Это было заявление самого Мухаммеда в отношении Корана. Вначале Мухаммед не был уверен на этот счет, он был не уверен и боялся делать такое заявление. Но затем, однако, он исполнился уверенности.

Теперь, нам бы хотелось пролить свет на Коран и его содержимое, для того, чтобы открыть истину нашим собратьям мусульманам, некоторые из которых прочитали о том, что известные исламские авторитеты говорили о Коране. Они также будут очень удивлены, если узнают, что соратники Мухаммеда также как и праведные халифы говорили о том, что некоторые части Корана были утеряны. Более того, Коран подвергся изменениям со стороны соратников Мухаммеда несогласных с некоторыми главами Корана, некоторыми стихами и их значением. Для мусульман практически невозможно вообразить такие вещи об их книге, которую они искреннее уважают и которой поклоняются.

Пелена тумана, которая окружает Коран должна быть рассеяна, и вуаль, которая закрывает его, должна исчезнуть. Если это беспокоит и раздражает мусульман, это также поможет им очнуться ото сна их заблуждения, которое не приносит им пользы, а напротив, наносит вред.

Научные ошибки в Коране

Мы начнем с того, что укажем на научные, исторические и грамматические (в соответствии с общеизвестными грамматическими правилами арабского) ошибки в Коране. Мусульмане верят, что неподражаемость Корана выражается в красноречии и высоком уровне арабского языка на котором он написан, поэтому, для них невозможно вообразить, что Коран полон ошибок. Сначала мы обратимся к трем научным ошибкам относящимся к Солнцу, Земле и другим объектам источающим свет и молнии.

Солнце

Буквально, Коран говорит, что один из праведных служителей Господа увидел в месте заката солнца горячий и мутный источник. Там этот человек нашел неких людей. Позвольте прочесть этот отрывок из Корана (сура «Пещера», аят 86),

«[Он шел] и прибыл, наконец, к [месту, где] закат солнца, и обнаружил, что оно заходит в мутный и горячий источник. Около него он нашел [неверных] людей. Мы сказали: «О Зу-л-карнайн! Либо ты их подвергнешь наказанию, либо окажешь милость». (Сура 18:86)

Чтобы не ошибиться в понимании значения этих странных коранических слов, я сошлюсь на известного исследователя Корана, а также на известных древних толкователей. Я узнал, что все они согласны о значении этого отрывка и говорят, что друзья Мухаммеда узнали о месте заката солнца и что он дали им такой ответ. Все исследователи, такие как Бейдави, Ас-Суйюти, и Замахшари подтверждают это. Замахшари пишет в своей книге «Каш-шаф»

«Абу Зарр (один из близких соратников Мухаммеда) был вместе с Мухаммедом во время заката. Мухаммед спросил его: «Знаешь ли ты, о Абу Зарр, где находится это место заката?» Он ответил: «Аллах и Его Посланник знают это лучше». Мухаммед сказал: «Оно садится в мутный источник» (3‑е изд., Т. 2 стр. 743, 1987).

В этой же книге «Свет Откровения» (с. 399), Бейдави отмечает:

«Солнце садится в мутном источнике; это колодец, который содержит ил. Некоторые из чтецов Корана, читают это следующим образом: «… горячем источнике», таким образом мы встречаем два сочетающихся описания. Упоминается что Ибн’ Аббасом слышал как Му’авийа в своем чтении также именовал источник горячим. Он сказал ему: «Он илистый». Му’авийа направлял посыльного к Ка’б ал-Ахбару и спрашивал его: «Где садится солнце?» Он отвечал – в воде и иле и там, где были некие люди. Таким образом он согласился с утверждением ибн аль-‘Аббаса. Был также поэт, который написал несколько строф, в которых упоминается о солнце садящемся в мутный источник».

Ас-Суйюти (с. 251) говорил, что солнце садится в колодец, который содержит мутный ил. Мы находим тот же текст и такую же интерпретацию в комментариях Табари (с. 339) так же как и в труде «Краткое изложение Табари» (с. 19 часть 2) в котором отмечается, что колодец в который садится солнце «содержит известняк и темный ил».

Это комментарии основных исламских авторитетов и ближайших сподвижников Мухаммеда, таких как ибн Аббас и Абу Зарр.

Гром и молнии

Широко известно, как говорит наука, что гром – звук обусловленный взаимодействием между электрическими зарядами облаков. Мухаммед, являющийся пророком для мусульман, имел другое мнение на этот счет. Он заявлял что гром и молния – два ангела Господа точно таких же, как Гавриил!

В Коране существует сура, под названием «Гром» в которой написано, что Гром восхваляет Господа. Мы можем считать, что это сказано не буквально, поскольку гром не является живым существом – хотя, в духовном плане, вся природа восхваляет Господа. Толкователи Корана и его главные знатоки, однако, настаивают, что Мухаммед сказал, что гром – ангел, точно такой же как ангел Гавриил. В своем комментарии (с. 329) на аят 13 суры Гром, Бейдави пишет:

«Ибн ‘Аббас спросил Посланника Аллаха о громе. Он сказал ему: «Это ангел, который в среде облаков, который (несет) с собой огонь и двигает облака».

В комментарии Ас-Суйюти (с. 206), мы читаем об этих стихах:

«Гром является ангелом, пекущемся об облаках, и двигающим их».

Не только ибн ‘Аббас спрашивал Мухаммеда о природе грома, но также и евреи. В книге «ал-Иткан» написанно Суйюти (ч. 4, стр. 230), мы читаем следующий диалог:

«Ибн ‘Аббас сказал, что он слышал, как евреи пришли к Пророку (мир ему) и спросили: «Скажи нам о громе. Что это?» Он сказал им:

«Это один из ангелов Аллаха пекущийся об облаках. Он несет в своих руках огонь, которым он прокалывает облака и двигает их в ту сторону, в которую прикажет ему Аллах». Они также спросили его: «Что за звук мы слышим?» Он сказал: «(Это) его голос (Голос ангела)».

Аналогичный случай – вопрос евреев и ответ Мухаммеда – упоминается большинством исследователей. Сошлемся, например, на ал-Сахих ал-Муснад Мин Асбаб Нузул ал-Айат (истории, касающиеся аятов Корана, с. 11) и ал-Каш-шаф, написанной Имамом аль-Замахшари (ч. 2, с. 518, 519). В ней повторяется та же история и те же слова Мухаммеда. Этот случай популярен среди мусульманских исследователей, упомянутый рассказ и диалог между Мухаммедом и евреями широко известен.

Мы уже упоминали, что сказал Бейдави, Ас-Суйюти, Замахшари, Суйюти и ибн ‘Аббас. Мы не знаем (среди древних исследователей) ни одного являющимся более авторитетным, чем упомянутые лица. Что касается молнии, Мухаммад утверждал, что это ангел, подобный грому и похожий на Гавриила и Михаила. На стр. 230 вышеупомянутого источника, Суйюти упоминает об этом. Также на стр. 68 части 4 «Иткан», Суйюти пишет имена ангелов: «Гавриил, Михаил, Харут, Марут, Гром и Молния (Он говорит), что у молнии есть четыре лица».

Суйюти приводит их под подзаголовком: «Имена Ангелов Аллаха». Он также упоминает, что Мухаммед сказал, что молния – это конец хвоста ангела Рафаила (часть 4, стр. 230 Иткана).

Земля

Несколько тысяч лет назад, в Священной Библии было ясно записано, что земля круглая, шарообразная и что она ни на что не опирается.

«Он есть Тот, Который восседает над кругом земли». Ис.40:22-31

«Он распростер север над пустотою, повесил землю ни на чем». Иов.26:7-14

«И владычествовала над обитателями земли с великим угнетением, и удерживала власть на земном шаре». 3Ездр.11:32

Коран же отрицает эти научно установленные факты. Во многих местах, упоминается, что земля плоская и что горы представляют собой как бы шесты, удерживающие Землю от опрокидывания. Позвольте нам остановиться на словах которые говорятся в Коране о Земле:

В суре 88:17, 20 написано:

«Неужели они не поразмыслят о том, как созданы верблюды… как простерта земля?»

На стр. 509, Ас-Суйюти пишет:

«Эта фраза: «как простерта», обозначает что земля плоская. Все исламские богословы согласны с этим. Она не круглая, как утверждают физики».

То чему учит Коран очевидно из комментариев Ас-Суйюти, что «Земля плоская, а не круглая, как ученые заявляют». Из слов Ас-Суйюти следует, что в Коране многократно указывается на то, что Земля плоская (см. 19:6, 79:30, 18:7, и 21:30). Также в Коране отмечается следующее:

«[Неужели они не знают], что Мы воздвигли на земле прочные горы, чтобы благодаря им она утвердилась прочно» (21:31).

Исследователи, которые одинаково толкуют смысл этого аята, верят в то, что говорится Ас-Суйюти (стр. 270–271).

«Аллах основал горы на Земле, чтобы она не трясла людей».

На стр 429, ал-Бейдави говорит:

«Аллах сотворил прочные горы на Земле чтобы она не сотрясалась и не трясла людей». Он также сотворил небеса как клетку и удерживает их от падения вниз».

В коране (Сура 50:7), мы находим и иные аяты, имеющие тот же самый смысл:

«Мы также простерли землю, воздвигли на ней горы недвижимые…». (50:17)

Эти слова сопровождаются аналогичным комментарием со стороны исламских теологов (см. Ас-Суйюти, стр. 437, Бейдави, стр. 686, Табари, стр. 589, Замахшари, ч. 4, стр. 381). Все они уверяют нас, что «если бы не было этих прочных гор, Земля бы сдвигалась».

Замкшари, Бейдави и Ас-Суйюти говорят: «Аллах сотворил небеса без опор, но Он поместил на Земле прочные горы, чтобы не было сотрясений». Касаясь Суры 50:7,Суйюти говорит, что теологи отмечают: «Каф (* название суры 50) – это гора которая охватывает внутреннюю часть Земли» (см. Иткан, ч. 3, стр. 29). Каф – арабская буква, аналогичная латинской «К».

Выше были дословно приведены комментарии древних исламских теологов. Однако религиозные исследователи из Саудовской Аравии выпустили несколько лет назад книгу чтобы опровергнуть шарообразность Земли, они заявили, что это миф, и согласились с вышеупомянутыми утверждениями теологов и написали, что мы должны верить Корану и не признавать шарообразности Земли.

Также широко известно, что Коран декларирует: существует семь слоев земли (см. комментарии Ас-Суйюти, стр. 476, аль-Бейдави, стр. 745 как интерпретируется Сура 61:12, Сура Развод: 12).

Совершенно ясно, что солнце не проходит через атмосферу и не садится в горячем, илистом колодце или в источнике мутной воды, или в месте, где находится и то и другое как утверждают Бейдави, Замахшари и Коран.

Ясно также, что молния не является ангелом Рафаилом, не является ангелом и Гром. Никогда ангел Гавриил не вдохновлял Мухаммеда на написания стихов о его друге ангеле-Громе. Гром и молния – природные явления, а не ангелы, похожие на Михаила и Гавриила, как утверждал пророк ислама.

Исторические ошибки Корана

Исторические ошибки настолько многочисленны в Коране, что мы не можем рассмотреть все из них, а выделим лишь несколько наиболее очевидных примеров.

Распятие Христа

Коран совершенно определенно отрицает, что Иисус был распят. Он заявляет, что евреи так запутались, что распяли кого-то другого, кто был похож на Христа. Об этом написано в Коране (4:15):

«А против тех из ваших жен, которые совершают прелюбодеяние, призовите в свидетели четырех из вас. Если они подтвердят [прелюбодеяние] свидетельством, то заприте [жен] в домах, пока их не упокоит смерть или Аллах не предназначит им иной путь.

«а они не убили его и не распяли, но это только представилось им»

В комментарии на этот аят аль-Бейдави говорит (стр. 135):

«Группа евреев прокляла Христа и его мать. Они навлекли на них зло, но (* Аллах), хвала Ему, превратил их в обезьян и свиней. Евреи объединились, чтобы убить его, но Аллах, хвала Ему, сообщил ему (Иисусу), что Он собирается вознести его на небеса. Таким образом (Иисус) сказал своим друзьям: «Кто похожий на меня, желает быть схваченным ими и убитым и распятым, а затем попасть в рай?» Один из них вызвался добровольно сделать это и Аллах сделал его похожим на Христа. Затем он был схвачен, распят и убит. Также говорят (о распятом), что он был предателем, которой пришел к толпе, чтобы привести ее к Христу (он имел ввиду иудеев), но Аллах сделал его похожим на Иисуса и он сам был арестован, распят и убит».

Аль-Бейдави не единственный кто писал эти мистические истории, напротив, все мусульманские теологии, которые пытались интерпретировать вышеупомянутый стих, четко утверждали, что Иисус не был распят. Коран игнорирует не только написанное Матфеем, Марком, Лукой и Иоанном вместе со всем Новым Заветом, но также и все исторические хроники. Он игнорирует историю Римской империи, в которой имеются документальные подтверждения того, что человек из еврейского народа под именем Иисус был распят во время правления Понтия Пилата, Римского наместника, который удовлетворил требования иудейских первосвященников.

Хорошо известно, что суд на Христом происходил перед лицом иудейских первосвященников и Римского наместника. Также хорошо известно, что арестованный человек не протестовал и не говорил: «Я не Христос, я Иуда, который хотел Его предать и отдать вам». Все слова Иисуса на кресте дают нам ясно понять, что он Христос, особенно его утверждения: «Отче! прости им, ибо не знают, что делают. И делили одежды Его, бросая жребий». Лук.23:34-56.

Иисус Сам говорил Своим ученикам, что Он должен быть доставлен на суд первосвященников и быть распятым, а затем воскреснуть от смерти на третий день. Иисус Сам предсказывал это, и то что распятие произойдет в соответствии со многими пророчествами из Ветхого Завета, которые предсказывали Его крестную смерть за века до этого события. Христос пришел исполнить волю Бога для спасения людей.

Таким образом, нет оснований для того, чтобы через шесть столетий после распятия Христа, появился человек и утверждал на весь мир (игнорируя все исторические свидетельства), что тот кто был распят не был Христом. Это все равно как если бы человек, который родится через шесть столетий после настоящего времени, говорил, что в двадцатом столетии был убит не Мартин Лютер Кинг, но кто-то другой, кто был похож на него. Конечно, никто ему не поверит, даже если он заявит что ангел Гавриил (или сотня ангелов) открыл ему это.

Дева Мария

Во многих местах Корана упоминается о Марии, как о сестре Моисея и Аарона, а так же как о дочери Имрана. Коран путает мать Иисуса с сестрой Аарона, поскольку обе женщины носили одно и то же имя, хотя одна из них жила несколькими веками позже другой. Коран утверждает, что у Марии (матери Христа) был брат, чье имя было Аарон (Сура 19:28) и отец по имени Имран (Сура 66:12). Их мать называется «жена Имрана» (Сура 3:35), что лишает нас всяких оснований сомневаться в том, что Мария, мать Иисуса, спутана с Марией, сестрой Аарона.

Мусульманские теологии признают, что это имеет место, они находятся в затруднительном положении и не способны найти какое-нибудь решение данной дилеммы. Давайте проверим их объяснения, чтобы увидеть противоречие между различными точками зрения.

В контексте этих комментариев кораническое утверждение о том, что Мария является сестрой Аарона (как написано в 19:28), аль-Бейдави (стр. 405) говорит:

«О сестра Харуна! За твоим отцом не водилось дурных склонностей, да и мать твоя не была женщиной распутной…» Также говорится, что она одна из потомков Аарона, хотя между временем их жизни прошло около тысячи лет. Также говорится, что он (Аарон) был праведным человеком или злым человеком, жившим в их время (время Марии). Они приравнивают ее к нему что бы посмеяться над ней или чтобы оскорбить ее».

Утверждение Бейдави повторяется в Коране, поскольку Коран не ссылается на моральные взаимоотношения, в нем делается ударение на буквальное значение. В Коране Мария возводится до уровня пророка Аарона, или до статуса дочери Имрана, почему же упоминается, что ее мать была женой Имрана как написано в Суре 3:35? Совершенно очевидно, что дело в одном из двух: либо что-то перепутал Мухаммед, либо ангел Гавриил! Нельзя принять слова Корана о том, что Мария имела тот же статус, что и сестра Аарона и дочь Имрана. Поэтому нельзя говорить о Марии (матери Иисуса) как будто она была сестрой Аарона и Моисея.

Современные исследователи которые перевели Коран, под эгидой Саудовских властей говорят (в предисловии к стр. 47 Суры «Семейство Имрана»).

«Аль Имран получила свое название из стиха 32, «семейство Имрана» (отца Моисея), как собирательное имя для всех еврейских пророков от Моисея до Иоанна Крестителя и Иисуса Христа. Это наряду с упоминанием матери Марии, как «жены Имрана» (стих 34) и слова «сестра Аарона» адресуются к Марии (XIX.28) стали причиной для обвинений в анахронизме. Некоторые говорят, что пророк спутал Марию, мать Иисуса, с Марией, сестрой Моисея. Большинство мусульман верят (на основании авторитета Корана) что дед Иисуса Христа был назван именем «Имран», которым мог быть также назван отец Моисея. В суре XIX 28, где Мария называется сестрой Аарона, они находят указание на наследственное происхождение наиболее возможным. В то же время отрицается всякая возможность того, что есть какие либо основания полагать, что Дева Мария не имела брата по имени Аарон».

Таким образом, нам не могут объяснить, почему Коран говорит, что мать Марии была женой Имрана, особенно с учетом того, что Коран подразумевает (как в нем говорится) только духовную взаимосвязь. Это явная историческая ошибка, мои дорогие читатели, потому что Мария не имела брата по имени Аарон.

Александр Македонский

Удивительно встретить в Коране повествование об Александре Македонском, как будто он был праведный человек или духовный учитель, в то время как хорошо известно, что, будучи греком, Александр, являлся идолопоклонником и провозглашал себя сыном Амуна, Бога Египта. Если читатель удивит сообщение о том, что где-то в Коране написано о праведности Александра, ему следует обратиться к суре 18:83–98, где мы можем насчитать шестнадцать стихов, которые повествуют об этом военном предводителе. Эти стихи ясно говорят, что Господь помогал ему, руководил им и устранял все препятствия на его пути, чтобы он мог исполнить свои планы и желания. Они свидетельствуют, что Александр был одним из тех, кто достиг места заката Солнца и нашел его садящимся в колодец полный воды и ила. В них утверждается, что он встретил неких людей, которых Господь дал ему право мучить их, убивать их или делать рабами, призывая их к вере и ставить на истинный путь.

Эти комментарии приводятся всеми исламскими богословами без исключения (см. Бейдави, стр. 3999, ал-Джалалн, стр. 251, ал-Табари, стр. 339, ал-Замакхшари, ч. 2 ал-Каш-шаф, стр. 743). Если же не обращаться к этим великим толкователям Корана, к кому же еще мы можем обращаться? Грек Александр не был праведником и слугой Бога как говорит Коран, напротив, он был безнравственным распущенным, агрессивным идолопоклонником. Он не имел никакого отношения к Богу и Господь никогда не просил его направлять людей и учить их вере.

Другие исторические ошибки

Поверит ли читатель, что Авраам хотел принести в жертву не Исаака, а Измаила? Так говорят все исламские богословы. Знаете ли Вы что Коран утверждает, что Хаман был правой рукой фараона, хотя Хаман жил в Вавилоне тысячи лет спустя? Коран говорит именно так. В Коране также утверждается, что Моисея из реки вытащила не его сестра, а его мать (28:6–8), и что Самаритяне выплавили золотого тельца для детей Израиля и сбили их с истинного пути (см. 20:85–88) хотя хорошо известно, что Самария в то время еще не существовала. Самария возникла после времен Вавилонского исхода. Как кто-то из Самаритян мог сделать золотого тельца для людей Израиля?

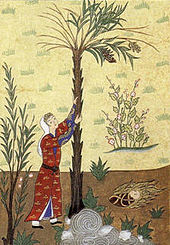

Что касается рождения Христа, Коран учит, что Дева Мария родила его под тенью пальмового дерева, а не в вертепе (см. 19:23). Коран игнорирует все документальные исторические свидетельства доступные людям на протяжении веков и делает для нас новые «открытия»!

В Коране заявляется (2:125–127), что Авраам и Измаил, его сын, были теми кто построил Каабу в Мекке (Саудовская Аравия). Позже Др. Таха Хуссейн (известнейший профессор арабской литературы в Египте) признал, что информация содержащаяся в Коране относит строительство Каабы к делам Авраама и Измаила, что исторически не засвидетельствовано. Он писал:

«Что касается этого эпизода, совершенно очевидно, что он имеет недавнее происхождение, эта история стала широкоупотребительной как раз незадолго до возникновения ислама. Ислам использовал ее по религиозным причинам» (цит. по Анвар ал-Джунди, Мизан ал-Ислам, стр. 170).

Это заявление спровоцировало шквал негодования и ненависти исламских богословов в отношении этого человека. Бывший президент Туниса встретился с тем же самым, когда заявил, что Коран содержит мифические истории. Исламские богословы восстали против него и пригрозили убить его, потому что Мухаммед приказал – убей всякого, кто выскажет оскорбления в адрес Корана. Таким образом, что же мог сделать Таха Хуссейн или Абу Рукайба (больше известный на Западе под именем Баурджиба) или что же можем сделать мы, если Коран отвергает большинство исторических фактов? Следует ли нам замолчать и стараться об этом не думать, чтобы не быть убитыми?

Коранический язык и грамматически ошибки

Наши мусульманские братья говорят, что красноречивость Корана, его превосходный язык и прекрасное изложение – ясное доказательство того, что Коран является Словом Бога, потому что неподражаемость Корана лежит в прекрасном арабском языке который мы находим в нем. Мы признаем, что Коран (в некоторых частях и главах) действительно написан с красноречием и выразительностью. Этот факт несомнен и всякий кто пытается отрицать его не понимает прелести арабского языка. Хотя, с другой стороны, мы можем сказать, что в Коране много языковых ошибок в некоторых из его частей, которые имеют отношение к стилю изложения языка, литературным выражениям и общепринятым грамматическим правилам арабского языка и языковым выражениям.

В Коране даже можно найти слова, которые не имеют никакого значения и не существуют ни в каких языках. Стоит также упомянут о лексике, которую никто не может понять. Соратники Мухаммеда признавали это, также как увидим мы, но прежде чем обратиться к этим вопросам, я хотел бы отметить две вещи.

Во-первых, с лингвистической точки зрения, красноречие какой бы то ни было книги не может быть доказательством ее величия или доказательством того, что она относится к Богу, поскольку для Бога свойственно проявлять Свою власть не в красноречивом изложении и выразительных классическом арабском языке, а скорее проявлять свою силу в великом духовном содержании, того что написано в книге, которая поможет вступить людям на высокий духовный уровень, который позволит им жить в мире и любви. Это помогает им получать наслаждение от глубокой внутренней радости и духовной, психологической полноты жизни. Господь не заботится о том, чтобы учить человечество правилам и принципам арабского языка. Господь не учит их выходящему из употребления классическому арабскому языку, но истинный живой Бог – наш духовный учитель любви и радости.

Действительно ли содержание Корана удовлетворяет условиям позволяющим приписать его Богу? Все что мы собираемся сделать в этой статье – что красноречие языка не всегда является доказательством того, что слова ниспосланы с небес или, что эти слова принадлежат пророку. Германский поэт Шиллер вовсе не пророк, Илиада и Одиссея написаны не пророками, а греческими поэтами. Непревзойденность поэм Шекспира, которые в англоязычной литературе публиковались чаще чем Коран более чем в 10 раз, вовсе не позволяет британцам говорить, что архангел Гавриил открыл их Шекспиру.

Во-вторых, весьма важно, что красноречие Корана и превосходный классический арабский язык, которым он написан создают трудности в чтении и понимании, даже для самих арабов. Что же говорить о людях для которых арабский язык не является родным? Коран будет оставаться для них проблемой, потому что для них недостаточно изучение арабского языка, чтобы читать Коран. Им для лучшего понимания необходимо изучать арабскую литературу и знать арабский в совершенстве. Мы также можем отметить, что большинство арабов не понимает классического арабского языка Корана, который содержит сотни слов, которые приводили в замешательство последователей Мухаммеда, которые, естественно арабский знали прекрасно, но не могли объяснить значение этих слов, наряду со многими другими словами, которые последователи Мухаммеда не понимали.

Джалал ал-Дин ас-Суйюти, под заглавиям «Инородные слова в Коране» посвятил по крайней мере сотню страниц во второй части своей знаменитой книги «Иткан», объяснению трудных слов включенных в суры Корана. Лексикон классического арабского языка и некоторые выражения более не используются среди арабов. Язык столь существенно изменился, что Шафииты говорят: «Никто всесторонне и исчерпывающе не знает языка за исключением пророка» (Иткан, часть II, стр. 106).

Естественно возникает вопрос: какая польза жителям планеты от того, что Книга Господа написана на труднопонимаемом языке, если его не совсем понимают даже арабы и соратники Мухаммеда? Неужели Господь ниспослал книгу, в которой многие слова заведомо непонятны, особенно с учетом того, что ученые последователи ислама говорят: Коран должен читаться только на арабском. В своей книге ал-Иткан, Ас-Суйюти пишет:

«Чтобы не терялась неподражаемость Корана, абсолютно недопустимо, чтобы Коран читался на любом языке за исключением арабского, независимо от того, владеет ли чтец языком или нет, в молитвенное время или в другое время. В соответствии с заявлениями Кафала (одного из наиболее известных знатоков исламского права, основ веры и толкований), невозможно себе представить чтение Корана на персидском. Он говорил: «Это значит исказить смысл божьего откровения, если кто-то хочет читать на Персидском он не сможет исполнить замыслы Аллаха».

Поэтому многие верующие, не являющиеся арабами, повторяют коранические тексты без понимания их сути. Та же мысль излагается Др. Шалаби в его книге «История исламских законов» (стр. 97). Он также добавляет:

«Если Коран переводится на другие языки, он теряет свое красноречие и неподражаемость. Неподражаемость принадлежит лишь только ему самому, только оригиналу. Позволительно переводить смыслы, не пытаясь воспроизвести все буквально».

Того же принципа следуют те, кто работает с английскими переводами. Они говорят (стр. 111): «Коран не может быть переведен – это традиционно утверждается шейхами. Коран на арабском – неподражаемая симфония, чрезвычайная глубина которой заставляет людей плакать и пребывать в экстазе».

Это верно. Если Коран буквально переводится на английский, например, он теряет свою лингвистическую прелесть, и не может быть сравнен с другими произведениями английской, французской или немецкой литературы. Некоторые также удивляются, как могут быть переведены многие арабские слова, для которых трудно или невозможно подобрать полные аналоги в другом языке.

Другой вопрос, который заставляет нас задуматься – принадлежит ли Господь только арабам? Если Его книга может быть прочтена только на арабском, тогда она написана только для арабов и не может быть прочитана на другом языке за исключением арабского, как доказывают исламские богословы – как будто Бог был Богом АРАБОВ. Так например, исламские богословы запрещают молиться Аллаху в мечетях на любом другом языке за исключением арабского. Также требуется чтобы призыв на молитву и исповедание веры, свидетельствующее о принадлежности к исламу, произносилось только на арабском языке, потому что Мухаммед (пророк ислама) сказал, что арабский язык – язык рая и арабы — лучшая нация среди людей.

Известное изречение сказанное Мухаммедом мусульманам таково: «Люблю арабов за три вещи: потому что я араб, Коран написан на арабском языке и люди в рае – арабы» (по ал-Мустадраку по Хакиму и Файд ал-Гхадир).

Позвольте теперь обратиться к ошибкам арабского языка, которые можно встретить в Коране, при этом мы будем учитывать следующий факт.

Оригинальный коранический текст был написан без использования диактрических знаков, огласовок и некоторые из произносимых звуков при письме опускались.

Мы попытаемся объяснить это англоязычным читателям как можно яснее. Мы надеемся, что это будет сочтено удивительным и интересным. Чтецы на арабском хорошо знают, что для того чтобы понимать значение слов, необходимо знать диактрические знаки, которые располагаются над или под буквами, иначе становится затруднительным (если не невозможным) сравнивать их значения. Огласовки также имеют важное значение для определения лингвистической интонации, вместе с написанием всех букв слова и без удаления любых из них. Так, многие читающие на арабском языке не могут представить себе, что Коран изначально был написан без использования столь существенных элементов, но позвольте нас заверить, что это является историческим фактом, широко известным и признанным всеми мусульманскими теологами без исключения.

Мы также увидим, что существует большое количество слов, в отношении значения которых исламские богословы не могут прийти к согласию. Одним из примеров, позволяет нам наглядно продемонстрировать природу этой проблемы. Позвольте рассмотреть арабскую букву «ба». Изменяя диактрические знаки, мы получим три различных буквы – «та», «ба», и «за» (tha). Таким образом, когда эти буквы пишутся без диактрических знаков, чтецу становится трудно понять, какое слово подразумевалось при написании.

Рассмотрим некоторые из слов. Одно из арабских написаний, в зависимости от способа расстановки диактрических знаков, может писаться следующим образом: «сожалеть», «растение», «дом», «девушка». Другой пример, в зависимости от расстановки диактрических знаков может получиться: «богатый», «глупый» и т.д. (Подобно тому, как на русском слово, записанное «КРВ» можно огласовать как «корова», «кровь», «криво» и т.п.) Без диактрических знаков трудно отличить одно слово от другого. Смысл слова отличается в зависимости от положения диактрических знаков. Многие из арабских алфавитов требуют присутствия диактрических знаков, для того, чтобы можно их было отличить друг от друга чтобы можно было отличить одно слово от другого.

В своей знаменитой книге «История исламских законов» (стр. 43), Др. Ахмад Шалаби, профессор исламской истории и цивилизации отмечает:

«Коран был написан куфическим письмом без диактрических знаков, огласовок. Не осталось никаких различий между словами «раб» и «рабы»; «обманывать» и «вводить друг друга в заблуждение»; между «исследовать» и «утверждать». Благодаря знаниям арабов о языке, их чтение было точным. Позже, когда неарабские нации приняли ислам, начали появляться ошибки в чтении Корана, когда эти не-арабы и арабы, чей язык был засорен, читали Коран. Неверное чтение иногда приводило к изменению смысла слов».

Перевод с английского — И. Огнева

The Qur’an and the Bible in the light of history and science

Противоречия и ошибки в коране

Противоречия Корана объективным фактам (фактам науки, реальности):

Сегодня никто не станет утверждать, что земля плоская, гром – это ангел, а солнце каждый вечер спускается в мутный источник на краю земли. А вот Коран, вроде бы непогрешимая(?) книга, утверждает!

О Солнце:

«[Он шел] и прибыл, наконец, к [месту, где] закат солнца, и обнаружил, что оно заходит в мутный и горячий источник . Около него он нашел [неверных] людей. Мы сказали: «О Зу-л-карнайн! Либо ты их подвергнешь наказанию, либо окажешь милость». (Сура 18:86)

— коран утверждает, будто солнце закатывается на ночь в «место покоя», где ожидает до утра приказа взойти снова.

О горах и сдвигающейся земле:

«[Неужели они не знают], что Мы воздвигли на земле прочные горы, чтобы благодаря им она утвердилась прочно» (Сура 21:31).

— коран утверждает, будто горы были воткнуты в землю как иголки, а не образовывались медленно и постепенно. Будто горы являются камешками, положенными на края «земного ковра» (см. ниже) чтобы удерживать землю от сворачивания или сдувания ветром.

Коран утверждает, что Земля — плоская:

(13:3) Он — тот, кто распростер (Madda) землю.

(15:19) И землю Мы распростерли (Madadnaha).

(20:53) Он, который сделал для вас землю равниной (Mahdan).

(2:22) который землю сделал для вас ковром (Firasha).

(43:10) который устроил для вас землю колыбелью (Mahdan)

(50:7) И землю Мы распростерли (Madadnaha)

(51:48) И землю Мы разостлали (Farashnaha)

(71:19) Аллах сделал для вас землю подстилкой (Bisata).

(78:6) Разве Мы не сделали землю кроватью (Mihada)

(88:20) и на землю, как она распростерта (Sutehat).

(91:6) и землей, и тем, что ее распростерло (Tahaha)

— Коран описывает форму земли следующими словами: Madda, Madadnaha, Firasha, Mahdan, Farashnaha, Bisata, Mihada, Tahaha и Sutehat — каждое из них означает «плоская». Ясно, что автор корана хотел сказать людям, что Земля именно плоская, и он использовал весь доступный арабский словарь, чтобы передать эту идею.

И можно ли допускать, что «летящими звездами» поражается сатана (37.6-10; 67.5; 72.6-9)?

(исламcкая астрономия такая исламcкая).

А что вы скажете на то, что молоко образуется в желудках коров между калом и кровью (16:66)?

(исламская биология ещё более исламская чем исламская астрономия).

Противоречие Корана другим «священным писаниям»:

В Коране утверждается, что Авраам хотел принести в жертву не Исаака, а Измаила, что Моисея из реки вытащила не его сестра, а его мать (28:6-8), что Самаритяне выплавили золотого тельца для детей Израиля (см. 20:85-88), что Дева Мария родила Иисуса под тенью пальмового дерева (см. 19:23), что Авраам и Измаил, его сын, были теми, кто построил Каабу в Мекке (2:125-127).

В Коране написано, что у Марии – матери Иисуса был брат Аарон (Харун) (19:28) и отец Имран (66:12). Их мать называется «жена Имрана» (3:35).

— Следовательно, в Коране просто перепутаны Мария, мать Иисуса, и Мариам – сестра Моисея и Аарона.

Иисус будучи младенцем разговаривал с людьми как взрослый человек, называя себя посланником Аллаха (3:46, 19:24,30). Также Иисус обещал в своих проповедях приход пророка, да не просто пророка, а пророка по имени Ахмад (61:6). Кроме того, Иисус враждовал с неверующими (61:14). Согласно Корану, Иисус не был распят, а это лишь показалось иудеям. (4: 156)

— всё это говорит о том, что Мухаммед был крайне невежественен в деталях христианской религии. Но он легко одурачил тысячи арабов, заявив будто ВСЕ предыдущие религиозные послания неверны, а он ОДИН единственный — знаток правды (что не помешало Мухаммеду впоследствии десятки раз противоречить самому себе).

Противоречие Корана фактам истории:

В Суре 18:83-98 много написано об Александре Македонском (Искандерун, Зу-ль-Карнайн). Здесь он представлен праведником, мусульманином, тогда как на самом деле он был самым настоящим «неверным», язычником, многобожником и провозглашал себя сыном Зевса (также Амона Ра).

В 7.121 фараон повелевает всех магов «четвертовать и потом распять», тогда как распятие было изобретено 1300 годами позже. Да и как вообще можно четвертовать (разорвать на четыре части), а потом ещё и распять (растянуть живого человека на перекладине)?

Противоречия Корана самому себе:

В Коране встречается много противоречий, которые почитаются мусульманами за замену «на лучшее или равное ему» (2:100). Мусульмане и сами находят в Коране около 200 таких «замен». Однако это противоречит 4.84: «Будь он (Коран) не от Аллаха, то, наверное, много противоречий нашли бы они в нем». Однако, что означают «замены», если не противоречия (вовсе не равные замены, а именно противоречащие друг другу), которых и на самом деле хватает:

Слова Аллаха изменяются или нет?

«Им радостная весть И в этой жизни, и в другой,

— Словам Аллаха перемены нет. Сие есть высшее свершенье.» (10:64)

«Когда Мы

заменяем один аят другим — Аллах лучше

знает то, что Он ниспосылает, — [неверные] говорят [Мухаммаду]: «Воистину, ты —

выдумщик». Да, большинство неверных не знает [истины].» (16:101)

Кто велит творить мерзкие поступки?

«Когда же они совершают какой-либо мерзкий поступок, они оправдываются так: «И наши отцы поступали так же, и Аллах велел нам [поступать] именно так». А ты [, Мухаммад,] отвечай: «Воистину, Аллах не велит совершать поступков мерзких. Неужели вы станете возводить на Аллаха то, о чем не ведаете?» (7:28)

«Когда Мы хотели погубить [жителей] какого-либо селения, то

по Нашей воле богачи их совершают мерзкие поступки, так что предопределение осуществлялось, и Мы истребляли их до последнего.» (17:16)

Так куда попадут немусульмане — в рай или в ад?

«Воистину, не должны страшиться и не будут опечалены

те, кто уверовал, а также иудеи, сабеи и христиане — [все] те, кто уверовал в

Аллаха и Судный день и кто совершал добрые деяния.» 2:69.

«Если же кто изберет иную веру кроме

ислама, то такое поведение не будет одобрено, и в будущей жизни он окажется

среди потерпевших урон.» (3:85)

Египетский фараон в одном месте потоплен, в другом — обратился в ислам (?!) и спасся.

«Мы переправили сынов Исраила (Израиля) через море, а Фараон и его войско последовали за ними, бесчинствуя и поступая враждебно. Когда же Фараон стал тонуть, он сказал: «Я уверовал в то, что нет Бога, кроме Того, в Кого уверовали сыны Исраила (Израиля). Я стал одним из мусульман».

Аллах сказал: «Только сейчас! А ведь раньше ты ослушался и был одним из распространяющих нечестие.

Сегодня Мы спасем твое тело, чтобы ты стал знамением для тех, кто будет после тебя». Воистину, многие люди пренебрегают Нашими знамениями.» (10:90-92)

— Фараон не мог «спастись» в духовном смысле этого слова, поскольку:

«В День воскресения Фараон возглавит свой народ и поведет их в Огонь. Отвратительно то место, куда их поведут!

Проклятия будут преследовать их здесь и в День воскресения. Отвратителен дар, которым их одарили!» (11:98-99)

— Итак, значит Фараон спасся лишь физически, а не духовно. Что противоречит:

«Фараону захотелось изгнать их с земли, но Мы потопили его и всех, кто был с ним.» (17:103)

«Фараон со своим войском бросился преследовать их, но море накрыло их полностью.»(20:78)

«Вот Мы разверзли для вас море, спасли вас и потопили род Фараона, тогда как вы наблюдали за этим.»(2:50)

«После них Мы отправили Мусу (Моисея) с Нашими знамениями к Фараону и его знати, но они поступили с ними несправедливо. Посмотри же, каким был конец злодеев!»(17:103)

Другие противоречия Корана самому себе:

Длительность «дня» в 32:4 определяется в 1 000 лет, а в 70:4 – в 50 000.

В 50:37 говорится, что творение неба и земли закончилось в 6 дней, тогда как в 41.8-11 говорится о 8 днях.

В 2:130,285 говорится о равенстве между всеми апостолами, тогда как в 2:254 об отличиях, о преимуществах одних над другими.

Существует противоречие и между 19:34 и 4:156 о том, умер Иисус или нет.

Во власти Аллаха находится «все, что на небесах и на земле. Все и вся повинуется Ему» (30:25), отсюда понятие предопределенности. Однако находятся и такие, которые не повиновались Ему (7:11).

Грех идолопоклонства не прощается Аллахом (4:51,117-118), но это относится не ко всем (4:152).

Можно не поститься, если накормишь очень бедного, и все же пост – обязанность каждого мусульманина (2:180,181).

Прелюбодеяние наказывается 100 ударами (24:2), или всё же содержанием взаперти до смерти (4:19) – все зависит от того, по какому стиху судить.

Молиться можно обращаясь в любую сторону: и небо, и восток, и запад («аллах — всеобъемлющий») (2:115), но всё же молиться следует, обращаясь к конкретному месту, а не в любую сторону (2:144).

Верующим предписан пост (2:183), но по ночам пост не действует (2:187).

Ненависть к многобожникам не должна толкать верующих на грех убийства (5:2), но убивать многобожников не только можно, но и нужно (9:35, 2:217).

Судить следует по справедливости (5:42), или всё же предвзято, считая всякого человека заведомо виновным (5:49).

В молитве следует пребывать всю ночь с небольшим перерывом (73:2), половину ночи или чуть меньше (73:3), или вовсе меньше двух третей или одну треть (73:20), да вообще лишь столько, сколько вам доступно (на сколько вас хватит) (73:20).

— видимо, обстановка не позволяла дать чёткие распоряжения и Мухаммед сделал уступку пастве в духе «оставляю это на вашу совесть». Хотя в других случаях он отдавал приказы не думая о мнении окружающих.

— всё это говорит о том, что Мухаммед сам не имел чётких представлений о структуре проповедуемой им религии и излагал СВОЮ позицию так, как видел её в данный момент, в зависимости от СВОЕГО настроения. Он сам НЕ ПОМНИЛ, что проповедовал по этому же поводу в прошлый раз, и поэтому противоречил своим же словам.

(по различным материалам исследований текста корана)

http://tao44.narod.ru/rel_oshibki_v_korane.htm

«Террористические’ аяты корана»

«Террористические» аяты корана. (ислам и терроризм)

Вы часто слышите от мусульман и некоторых политиков, будто ислам — мирная религия, не одобряет насилие, терпимо относится к представителям других религий и неверующим? Давайте проверим, так ли это? Вот, что говорил мусульманам Мухаммед (как велел поступать, если мусульмане конфликтуют с НЕмусульманами):

2:191 Убивайте [неверующих], где бы вы их ни встретили, изгоняйте их из тех мест, откуда они вас изгнали, ибо для них неверие хуже, чем смерть от вашей руки. И не сражайтесь с ними у Запретной мечети, пока они не станут сражаться в ней с вами. Если же они станут сражаться [у Запретной мечети], то убивайте их. Таково воздаяние неверным!

(- несогласие с исламом объявляется поводом для убийства несогласных. при этом убийство НЕмусульман объявляется благим делом.)

4:74 Пусть сражаются во имя Аллаха те, которые покупают будущую жизнь [ценой] жизни в этом мире. Тому, кто будет сражаться во имя Аллаха и будет убит или победит, Мы даруем великое вознаграждение.

(- прямой призыв к совершению суицидальных терактов.)

4:84 Сражайся во имя Аллаха. Ты ответственен не только за себя, поэтому побуждай к этому других верующих. Быть может, Аллах отвратит от вас ярость неверующих. Ведь Аллах сильнее всех в ярости и в наказании.

(- призыв не только вести бандитскую деятельность, но и активно вовлекать в неё окружающих.)

4:91: «И ты увидишь, что есть и другие [мунафики], которые хотят быть верными и вам, и своему народу. Всякий раз, когда ввергают их в смуту [с муслимами], они увязают в ней. И если они не отойдут от вас и не предложат вам мира и не перестанут нападать на вас, то хватайте их и убивайте, где бы вы их ни обнаружили. Мы вам предоставили полное право [сражаться] с ними.»

(- имеются ввиду, например, светские власти, которые вроде бы благосклонны к религии, но при этом вводят либеральные законы принятые международным сообществом, освобождающие людей от религиозных повинностей и ограничивающие права религии.)

5:51 О вы, которые уверовали! Не дружите с иудеями и христианами: они дружат между собой. Если же кто-либо из вас дружит с ними, то он сам из них. Воистину, Аллах не ведет прямым путем нечестивцев.

(- призыв всегда быть готовым пойти против иудеев и христиан.)

8:39 Сражайтесь с неверными, пока они не перестанут совращать [верующих с пути Аллаха] и пока они не будут поклоняться только Аллаху. Если же они будут [совращать с пути верующих], то ведь Аллах видит то, что они вершат.

(- ни о каком противостоянии военному нападению речи не идёт! тут откровенный призыв вести террористическую войну против всех, кто НЕ считает ислам достойным доверия!)

8:60 Приготовьте [, верующие,] против неверующих сколько можете военной силы и взнузданных коней — таким образом вы будете держать в страхе врагов Аллаха и ваших врагов, а сверх того и иных [врагов], о которых вы и не догадываетесь, но Аллаху ведомо о них. И сколько бы вы ни потратили на пути Аллаха, вам будет уплачено сполна и к вам не будет проявлена несправедливость.

(- террор, акции устрашения, демонстрация агрессии объявляются основой безопасности ислама.)

9:5 Когда же завершатся запретные месяцы, то убивайте многобожников, где бы вы их ни обнаружили, берите их в плен, осаждайте в крепостях и используйте против них всякую засаду. Если же они раскаются, будут совершать салат, раздавать закат, то пусть идут своей дорогой, ибо Аллах — прощающий, милосердный.

(- именно принятие ислама врагами объявляется условием мира с ними.)

9:29 Сражайтесь с теми из людей Писания, кто не верует ни в Аллаха, ни в Судный день, кто не считает запретным то, что запретили Аллах и Его Посланник, кто не следует истинной религии, пока они не станут униженно платить джизйу собственноручно.

(- тут призыв убивать иудеев и христиан, которые не приняли ислам как «очищение» религии).

9:36 Так не причиняйте же в эти месяцы вреда сами себе и, объединившись, сражайтесь все с многобожниками, подобно тому как они сражаются с вами все [вместе]. Знайте, что Аллах — на стороне богобоязненных

9:123 О вы, которые уверовали! Сражайтесь с теми неверными, которые находятся вблизи вас. И пусть они убедятся в вашей твердости. И знайте, что Аллах — на стороне набожных.

(- призыв вести подрывную деятельность против своих соседей, своего государства.)

47:4 Когда вы встречаетесь с неверными [в бою], то рубите им голову. Когда же вы разобьете их совсем, то крепите оковы [пленных]. А потом или милуйте, или же берите выкуп [и так продолжайте], пока война не завершится. Так оно и есть. А если бы Аллах пожелал, то Он покарал бы их Сам, но Он хочет испытать одних из вас посредством других. [Аллах] никогда не даст сгинуть понапрасну деяниям тех, кто был убит [в сражении] во имя Его.

(- призыв к торговле людьми, рабовладельчеству, захвату заложников).

______________

Именно эти части (аяты) корана мусульманские террористы истолковывают как обязанность каждого мусульманина вести вечную непрерывную войну против всех НЕмусульман. Некоторые политики и религиозные лидеры пытаются оправдать коран, говоря, будто мусульманские террористы просто «неправильно понимают коран», однако, эти их оправдания не устраняют того факта, что именно ЭТИ СТРОКИ КОРАНА явились основой современного ИСЛАМСКОГО ТЕРРОРИЗМА.

Как оправдываются террористы? Они заявляют, что сегодня в мире происходит точно такая же ситуация, которая описана в коране и при которой коран обязывает мусульман вести войну против немусульман. Страны Запада, по мнению исламистов, сегодня «оккупировали» исламские территории и «притесняют» мусульман; а простые люди — соседи мусульман «отвращают» их от ислама просто потому что не ведут исламский образ жизни. Поэтому мусульмане считают себя вправе вести ТЕРРОРИСТИЧЕСКУЮ войну против «оккупантов и предателей», согласно разрешениям и призывам из корана. И все разговоры о том, что ислам не одобряет терроризм — враньё. Ислам потворствует терроризму, а предлог для развязывания террора у особо ревностных мусульман всегда найдётся.

И как вообще можно говорить о мирном характере религии, проповедь которой основана на ненависти к инакомыслящим, запугивании адом и требованиях «убивать» всех несогласных и сопротивляющихся?

http://tao44.narod.ru/rel_islam_terrorism.htm

Criticism of the Quran is an interdisciplinary field of study concerning the factual accuracy of the claims and the moral tenability of the commands made in the Quran, the holy book of Islam. The Quran is viewed to be the scriptural foundation of Islam and is believed by Muslims to have been sent down by God (Allah) and revealed to Muhammad by the archangel Jabreel, also spelt Jibraeel (Gabriel). It has been subject to criticism both in the sense of being studied by mostly secular Western scholars and in being found fault with.

In «critical-historical study» scholars (such as John Wansbrough, Joseph Schacht, Patricia Crone, Michael Cook) seek to investigate and verify the Quran’s origin, text, composition, history,[1] examining questions, puzzles, difficult text, etc. as they would non-sacred ancient texts.[2] The most common criticisms concern various pre-existing sources that Quran relies upon, internal consistency, clarity and ethical teachings. According to Toby Lester, many Muslims find not only the religious fault-finding but also Western scholarly investigation of textual evidence «disturbing and offensive».[1]

Historical authenticity[edit]

Traditional view[edit]

According to Islamic tradition, the Quran is the literal word of God as recited to the Islamic prophet Muhammad through the angel Gabriel. Muhammad, according to tradition, recited perfectly what the archangel Gabriel revealed to him for his companions to write down and memorize.[5]

The early Arabic script transcribed 28 consonants, of which only 6 can be readily distinguished, the remaining 22 having formal similarities which means that what specific consonant is intended can only be determined by context. It was only with the introduction of Arabic diacritics some centuries later, that an authorized vocalization of the text, and how it was to be read, was established and became canonical.[6]

Prior to this period, there is evidence that the unpointed text could be read in different ways, with different meanings. Tabarī prefaces his early commentary on the Quran illustrating that the precise way to read the verses of the sacred text was not fixed even in the day of the Prophet. Two men disputing a verse in the text asked Ubay ibn Ka’b to mediate, and he disagreed with them, coming up with a third reading. To resolve the question, the three went to Muhammad. He asked first one-man to read out the verse, and announced it was correct. He made the same response when the second alternative reading was delivered. He then asked Ubay to provide his own recital, and, on hearing the third version, Muhammad also pronounced it ‘Correct!’. Noting Ubay’s perplexity and inner thoughts, Muhammad then told him, ‘Pray to God for protection from the accursed Satan.’[7]

Comparison with biblical narratives[edit]

The Quran mentions more than 50 people previously mentioned in the Bible, which predates it by several centuries. Stories related in the Quran usually focus more on the spiritual significance of events rather than details.[8] The stories are generally comparable, but there are differences. One of the most famous differences is the Islamic view of Jesus’ crucifixion. The Quran maintains that Jesus was not actually crucified and did not die on the cross. The general Islamic view supporting the denial of crucifixion is similar to Manichaeism (Docetism), which holds that only Jesus’ body was crucified but not his spirit, while concluding that Jesus will return during the end-times.[9]

That they said (in boast), «We killed Christ Jesus the son of Mary, the Messenger of Allah»;- but they killed him not, nor crucified him, but so it was made to appear to them, and those who differ therein are full of doubts, with no (certain) knowledge, but only conjecture to follow, for of a surety they killed him not:-

Nay, Allah raised him up unto Himself; and Allah is Exalted in Power, Wise;-

Earliest witness testimony[edit]

The last recensions to make an official and uniform Quran in a single dialect were effected under Caliph Uthman (644–656) starting some twelve years after the Prophet’s death and finishing twenty-four years after the effort began, with all other existing personal and individual copies and dialects of the Quran being burned:

When they had copied the sheets, Uthman sent a copy to each of the main centres of the empire with the command that all other Qur’an materials, whether in single sheet form, or in whole volumes, were to be burned.[11]

It is traditionally believed the earliest writings had the advantage of being checked by people who already knew the text by heart, for they had learned it at the time of the revelation itself and had subsequently recited it constantly. Since the official compilation was completed two decades after Muhammad’s death, the Uthman text has been scrupulously preserved. Bucaille believed that this did not give rise to any problems of this Quran’s authenticity.[12]

Regarding who was the first to collect the narrations, and whether or not it was compiled into a single book by the time of Muhammad’s death is contradicted by witnesses living when Muhammad lived, several historical narratives appear:

Zaid b. Thabit said:

The Prophet died and the Qur’an had not been assembled into a single place.[13]

It is reported… from Ali who said:

May the mercy of Allah be upon Abu Bakr, the foremost of men to be rewarded with the collection of the manuscripts, for he was the first to collect (the text) between (two) covers.[14]

It is reported… from Ibn Buraidah who said:

The first of those to collect the Qur’an into a mushaf (codex) was Salim, the freed slave of Abu Hudhaifah.[15]

Extant copies prior to Uthman version[edit]

Sanaa manuscript[edit]

The Sana’a manuscript contains older portions of the Quran showing variances different from the Uthman copy. The parchment upon which the lower codex of the Sana’a manuscript is written has been radiocarbon dated with 99% accuracy to before 671 CE, with a 95.5% probability of being older than 661 CE and 75% probability from before 646 CE.[16] The Sana’a palimpsest is one of the most important manuscripts of the collection in the world. This palimpsest has two layers of text, both of which are Quranic and written in the Hijazi script. While the upper text is almost identical with the modern Qurans in use (with the exception of spelling variants), the lower text contains significant diversions from the standard text. For example, in sura 2, verse 87, the lower text has wa-qaffaynā ‘alā āthārihi whereas the standard text has wa-qaffaynā min ba’dihi. The Sana’a manuscript has exactly the same verses and the same order of verses as the standard Quran.[17] The order of the suras in the Sana’a codex is different from the order in the standard Quran.[18] Such variants are similar to the ones reported for the Quran codices of Companions such as Ibn Masud and Ubay ibn Ka’b. However, variants occur much more frequently in the Sana’a codex, which contains «by a rough estimate perhaps twenty-five times as many [as Ibn Mas’ud’s reported variants]».[19]

Birmingham/Paris manuscript[edit]

In 2015, the University of Birmingham disclosed that scientific tests may show a Quran manuscript in its collection as one of the oldest known and believe it was written close to the time of Muhammad. The findings in 2015 of the Birmingham Manuscripts lead Joseph E. B. Lumbard, Assistant Professor of Classical Islam, Brandeis University, to comment:[20]

These recent empirical findings are of fundamental importance. They establish that as regards the broad outlines of the history of the compilation and codification of the Quranic text, the classical Islamic sources are far more reliable than had hitherto been assumed. Such findings thus render the vast majority of Western revisionist theories regarding the historical origins of the Quran untenable.

Tests by the Oxford Radiocarbon Accelerator Unit indicated with a probability of more than 94 percent that the parchment dated from 568 to 645.[21] Dr Saud al-Sarhan, Director of Center for Research and Islamic Studies in Riyadh, questions whether the parchment might have been reused as a palimpsest, and also noted that the writing had chapter separators and dotted verse endings – features in Arabic scripts which are believed not to have been introduced to the Quran until later.[21] Al-Sarhan’s criticisms was affirmed by several Saudi-based experts in Quranic history, who strongly rebut any speculation that the Birmingham/Paris Quran could have been written during the lifetime of the Prophet Muhammad. They emphasize that while Muhammad was alive, Quranic texts were written without chapter decoration, marked verse endings or use of coloured inks; and did not follow any standard sequence of surahs. They maintain that those features were introduced into Quranic practice in the time of the Caliph Uthman, and so the Birmingham leaves could have been written later, but not earlier.[22]

Professor Süleyman Berk of the faculty of Islamic studies at Yalova University has noted the strong similarity between the script of the Birmingham leaves and those of a number of Hijazi Qurans in the Turkish and Islamic Arts Museum, which were brought to Istanbul from the Great Mosque of Damascus following a fire in 1893. Professor Berk recalls that these manuscripts had been intensively researched in association with an exhibition on the history of the Quran, The Quran in its 1,400th Year held in Istanbul in 2010, and the findings published by François Déroche as Qur’ans of the Umayyads in 2013.[23] In that study, the Paris Quran, BnF Arabe 328(c), is compared with Qurans in Istanbul, and concluded as having been written «around the end of the seventh century and the beginning of the eighth century.»[24]

In December 2015 Professor François Déroche of the Collège de France confirmed the identification of the two Birmingham leaves with those of the Paris Qur’an BnF Arabe 328(c), as had been proposed by Dr Alba Fedeli. Prof. Deroche expressed reservations about the reliability of the radiocarbon dates proposed for the Birmingham leaves, noting instances elsewhere in which radiocarbon dating had proved inaccurate in testing Qurans with an explicit endowment date; and also that none of the counterpart Paris leaves had yet been carbon-dated. Jamal bin Huwaireb, managing director of the Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum Foundation, has proposed that, were the radiocarbon dates to be confirmed, the Birmingham/Paris Qur’an might be identified with the text known to have been assembled by the first Caliph, Abu Bakr, between 632 and 634 CE.[25]

Further research and findings[edit]

Critical research of historic events and timeliness of eyewitness accounts reveal the effort of later traditionalists to consciously promote, for nationalistic purposes, the centrist concept of Mecca and prophetic descent from Ismail, in order to grant a Hijazi orientation to the emerging religious identity of Islam:

For, our attempt to date the relevant traditional material confirms on the whole the conclusions which Schacht arrived at from another field, specifically the tendency of isnads to grow backwards.[26]

In their book 1977 Hagarism: The Making of the Islamic World, written before more recent discoveries of early Quranic material, Patricia Crone and Michael Cook challenge the traditional account of how the Quran was compiled, writing that «there is no hard evidence for the existence of the Koran in any form before the last decade of the seventh century.»[27][28] Crone, Wansbrough, and Nevo argued, that all the primary sources which exist are from 150 to 300 years after the events which they describe, and thus are chronologically far removed from those events.[29][30][31]

It is generally acknowledged that the work of Crone and Cook was a fresh approach in its reconstruction of early Islamic history, but the theory has been almost universally rejected.[32] Van Ess has dismissed it stating that «a refutation is perhaps unnecessary since the authors make no effort to prove it in detail … Where they are only giving a new interpretation of well-known facts, this is not decisive. But where the accepted facts are consciously put upside down, their approach is disastrous.»[33] R. B. Serjeant states that «[Crone and Cook’s thesis]… is not only bitterly anti-Islamic in tone, but anti-Arabian. Its superficial fancies are so ridiculous that at first one wonders if it is just a ‘leg pull’, pure ‘spoof’.»[34] Francis Edward Peters states that «Few have failed to be convinced that what is in our copy of the Quran is, in fact, what Muhammad taught, and is expressed in his own words».[35]

In 2006, legal scholar Liaquat Ali Khan claimed that Crone and Cook later explicitly disavowed their earlier book.[36][37] Patricia Crone in an article published in 2006 provided an update on the evolution of her conceptions since the printing of the thesis in 1976. In the article she acknowledges that Muhammad existed as a historical figure and that the Quran represents «utterances» of his that he believed to be revelations. However she states that the Quran may not be the complete record of the revelations. She also accepts that oral histories and Muslim historical accounts cannot be totally discounted, but remains skeptical about the traditional account of the Hijrah and the standard view that Muhammad and his tribe were based in Mecca. She describes the difficulty in the handling of the hadith because of their «amorphous nature» and purpose as documentary evidence for deriving religious law rather than as historical narratives.[38]

The author of the Apology of al-Kindy Abd al-Masih ibn Ishaq al-Kindi (not the famed philosopher al-Kindi) claimed that the narratives in the Quran were «all jumbled together and intermingled» and that this was «an evidence that many different hands have been at work therein, and caused discrepancies, adding or cutting out whatever they liked or disliked».[39] Bell and Watt suggested that the variation in writing style throughout the Quran, which sometimes involves the use of rhyming, may have indicated revisions to the text during its compilation. They claimed that there were «abrupt changes in the length of verses; sudden changes of the dramatic situation, with changes of pronoun from singular to plural, from second to third person, and so on».[40] At the same time, however, they noted that «[i]f any great changes by way of addition, suppression or alteration had been made, controversy would almost certainly have arisen; but of that there is little trace.» They also note that «Modern study of the Quran has not in fact raised any serious question of its authenticity. The style varies, but is almost unmistakable.»[41]

Lack of secondary evidence and textual history[edit]

The traditional view of Islam has also been criticized for the lack of supporting evidence consistent with that view, such as the lack of archaeological evidence, and discrepancies with non-Muslim literary sources.[42] In the 1970s, what has been described as a «wave of skeptical scholars» challenged a great deal of the received wisdom in Islamic studies.[43]: 23 They argued that the Islamic historical tradition had been greatly corrupted in transmission. They tried to correct or reconstruct the early history of Islam from other, presumably more reliable, sources such as coins, inscriptions, and non-Islamic sources. The oldest of this group was John Wansbrough (1928–2002). Wansbrough’s works were widely noted, but perhaps not widely read.[43]: 38 In 1972, a cache of ancient Qurans was discovered in a mosque in Sana’a, Yemen – commonly known as the Sana’a manuscripts. On the basis of studies of the trove of Quranic manuscripts discovered in Sana’a, Gerd R. Puin concluded that the Quran as we have it is a ‘cocktail of texts’, some perhaps preceding Muhammad’s day, and that the text as we have it evolved.[28] However, other scholars, such as Asma Hilali presumed that the San’aa palimpsest seems to be written down by a learning scribe as a form of «exercise» in the context of a «school exercise», which explains a potential reason of variations in this text from the standard Quran Mushafs available today (see Sanaa manuscript for details). Another way to explain these variations is that San’aa manuscript may have been part of a surviving copy of Quranic Mus’haf which escaped the 3rd caliph Uthman’s attempt to destroy all the dialects (Ahruf) of Quran except the Quraishi one (in order to unite the Muslims of that time).

Claim of divine origin[edit]

Questions about the text[edit]

The Quran itself states that its revelations are themselves «miraculous ‘signs‘«[44]—inimitable (I’jaz) in their eloquence and perfection[45]

and proof of the authenticity of Muhammad’s prophethood. (For example 2:2, 17:88-89, 29:47, 28:49)

[Note 1]

Several verses remark on how the verses of the book set clear or make things clear,[Note 2] and are in «pure and clear» Arabic language [Note 3]

At the same time, (most Muslims believe) some verses of the Quran have been abrogated (naskh) by others and these and other verses have sometimes been revealed in response or answer to questions by followers or opponents.[47][48][49]

Not all early Muslims agreed with this consensus. Muslim-turned-skeptic Ibn al-Rawandi (d.911) dismissed the Quran as «not the speech of someone with wisdom, contain[ing] contradictions, errors and absurdities».[50]

In response to claims that the Quran is a miracle, 10th-century physician and polymath Muhammad ibn Zakariya al-Razi wrote (according to his opponent Abu Hatim Ahmad ibn Hamdan al-Razi),

You claim that the evidentiary miracle is present and available, namely, the Koran. You say: «Whoever denies it, let him produce a similar one.» Indeed, we shall produce a thousand similar, from the works of rhetoricians, eloquent speakers and valiant poets, which are more appropriately phrased and state the issues more succinctly. They convey the meaning better and their rhymed prose is in better meter. … By God what you say astonishes us! You are talking about a work which recounts ancient myths, and which at the same time is full of contradictions and does not contain any useful information or explanation. Then you say: «Produce something like it»?![51][52]

Early Western scholars also often attacked the literary merit of the Quran.

Orientalist Thomas Carlyle, [Note 4] called the Quran «toilsome reading and a wearisome confused jumble, crude, incondite» with «endless iterations, long-windedness, entanglement» and «insupportable stupidity».[54] Salomon Reinach wrote that this book warrants «little merit … from a literary point of view».[Note 5]

More specifically, «peculiarities» in the text have been alleged.[56]

Iranian rationalist and scholar Ali Dashti points out that before its perfection became an issue of Islamic doctrine, early Muslim scholar Ibrahim an-Nazzam «openly acknowledged that the arrangement and syntax» of the Quran was less than «miraculous».[57]

Ali Dashti states that «more than one hundred» aberrations from «the normal rules and structure of Arabic have been noted» in the Quran.[58]

sentences which are incomplete and not fully intelligible without the aid or commentaries; foreign words, unfamiliar Arabic words, and words used with other than the normal meaning; adjectives and verbs inflected without observance of the concords of gender and number; illogically and ungrammatically applied pronouns which sometimes have no referent; and predicates which in rhymed passages are often remote from the subjects.[59]

Scholar Gerd R. Puin puts the number of unclear verses much higher:

The Koran claims for itself that it is ‘mubeen,’ or ‘clear,’ but if you look at it, you will notice that every fifth sentence or so simply doesn’t make sense. Many Muslims—and Orientalists—will tell you otherwise, of course, but the fact is that a fifth of the Koranic text is just incomprehensible. This is what has caused the traditional anxiety regarding translation. If the Koran is not comprehensible—if it can’t even be understood in Arabic—then it’s not translatable. People fear that. And since the Koran claims repeatedly to be clear but obviously is not—as even speakers of Arabic will tell you—there is a contradiction. Something else must be going on.[1]

Scholar of the Semitic languages Theodor Noldeke collected a large quantity of morphological and syntactic grammatical forms in the Quran[60] that «do not enter into the general linguistic system of Arabic».[61]

Alan Dundes points out the Quran itself denies that there can be errors within it, «If it were from other than Allah, they would surely have found in it many contradictions». (Q.4:82)[62]

Narrative voice: Mohammed or God as speakers[edit]

Since the Quran is God’s revelation to humanity, critics have wondered why in many verses, God is being addressed by humans, instead of Him addressing human beings. Or as sympathetic Western scholars Richard Bell and W. Montgomery Watt point out, it is not unheard of for someone (especially someone very powerful) to speak of himself in the third person, «the extent to which we find the Prophet apparently being addressed and told about God as a third person, is unusual», as is where «God is made to swear by himself».[63])[63]

Folklorist Alan Dundes notes how one «formula» or phrase («… acquit thou/you/them/him of us/your/their/his evil deeds») is repeated with a variety of voices both divine and human, singular and plural:

- `Our Lord, forgive Thou our sins and acquit us of our evil deeds` 3:193;

- `We will acquit you of your evil deeds`, 4:31;

- `I will acquit you of your evil deeds`, 5:12;

- `He will acquit them of their evil deeds`, 47:2;

- `Allah will acquit him of his evil deeds`, 64:9;[64]

The point-of-view of God changes from third person («He» and «His» in Exalted is He who took His Servant by night from al-Masjid al-Haram to al-Masjid al- Aqsa), to first person («We» and «Our» in We have blessed, to show him of Our signs), and back again to third («He» in Indeed, He is the Hearing) all in the same verse. (In Arabic there is no capitalization to indicate divinity.) Q.33:37 also starts by referring to God in the third person, is followed by a sentence with God speaking in first person (we gave her in marriage …) before returning to third person (and God’s commandment must be performed).[65] Again in 48:1 48:2 God is both first (We) and third person (God, His) within one sentence.[66]

The Jewish Encyclopedia, for example, writes: «For example, critics note that a sentence in which something is said concerning Allah is sometimes followed immediately by another in which Allah is the speaker (examples of this are Q.16.81, 27:61, 31:9, 43:10) Many peculiarities in the positions of words are due to the necessities of rhyme (lxix. 31, lxxiv. 3).»[56] The verse 6:114 starts out with Muhammad talking in first person (I) and switches to third (you).

- 6:114 Shall I seek other than Allah for judge, when He it is Who hath revealed unto you (this) Scripture, fully explained? Those unto whom We gave the Scripture (aforetime) know that it is revealed from thy Lord in truth. So be not thou (O Muhammad) of the waverers.

While some (Muhammad Abdel Haleem) have argued that «such grammatical shifts are a traditional aspect of Arabic rhetorical style»,[Note 6] Ali Dashti (also quoted by critic Ibn Warraq) notes that in many verses «the speaker cannot have been God». The opening surah Al-Fatiha[70] which contains such lines as

Praise to God, the Lord of the Worlds, …

You (alone) we worship and from You (alone) we seek help. …

is «clearly addressed to God, in the form of a prayer.»[71][70][72]

Other verses (the beginning of 27:91, «I have been commanded to serve the Lord of this city …»; 19:64, «We come not down save by commandment of thy Lord») also makes no sense as a statement of an all-powerful God.

Many (in fact 350) verses in the Quran[70] where God is addressed in the third person are preceded by the imperative «say/recite!» (qul) — but it does not occur in Al-Fatiha and many other similar verses. Sometimes the problem is resolved in translations of the Quran by the translators adding «Say!» in front of the verse (Marmaduke Pickthall and N. J. Dawood for Q.27.91,[73] Abdullah Yusuf Ali for Q.6:114).[70]

Dashti notes that in at least one verse

- 17:1 — Exalted is He who took His Servant by night from al-Masjid al-Haram to al-Masjid al-Aqsa, whose surroundings We have blessed, to show him of Our signs. Indeed, He is the Hearing, the Seeing.

This feature did not escape the notice of some early Muslims.

Ibn Masud — one of the companions of Muhammad who served as a scribe for divine revelations received by Muhammad and is considered a reliable transmitter of ahadith — did not believe that Surah Fatihah (or two other surah — 113 and 114 — that contained the phrase «I take refuge in the Lord») to be a genuine part of the Quran.[74] He was not alone, other companions of Muhammad disagreed over which surahs were part of the Quran and which not.[70] A verse of the Quran itself (15:87) seems to distinguish between Fatihah and the Quran:

- 15:87 — And we have given you seven often repeated verses [referring to the seven verses of Surah Fatihah] and the great Quran. (Al-Quran 15:87)[75]

Al-Suyuti, the noted medieval philologist and commentator of the Quran thought five verses had questionable «attribution to God» and were likely spoken by either Muhammad or Gabriel.[70]

Cases where the speaker is swearing an oath by God, such as surahs 75:1–2 and 90:1, have been made a point of criticism.[citation needed] But according to Richard Bell, this was probably a traditional formula, and Montgomery Watt compared such verses to Hebrews 6:13. It is also widely acknowledged that the first-person plural pronoun in Surah 19:64 refers to angels, describing their being sent by God down to Earth. Bell and Watt suggest that this attribution to angels can be extended to interpret certain verses where the speaker is not clear.[76]

- Spelling, syntax and grammar

In 2020, a Saudi news website published an article[77] claiming that while most Muslims believe the text established by third caliph ‘Uthman bin ‘Affan «is sacred and must not be amended», there are some 2500 «errors of spelling, syntax and grammar» within it. The author (Ahmad Hashem) argues that while the recitation of the Quran is divine, the Quranic script established by Uthman’s «is a human invention» subject to error and correction. Examples of some of the errors he gives are:

- Surah 68, verse 6, [the word] بِأَيِّيكُمُ [«which of you»] appears, instead of بأيكم. In other words, an extra ي was added.

- Surah 25, verse 4, [the word] جَآءُو [«they committed»] appears, instead of جَاءُوا or جاؤوا. In other words, the alif in the plural masculine suffix وا is missing.

- Surah 28, verse 9, the word امرأت [«wife»] appears, instead of امرأة.[78]

- Phrases, sentences or verse that seem out of place and were likely to have been transposed.

An example of an out-of-place verse fragment is found in Surah 24 where the beginning of a verse — (Q.24:61) «There is not upon the blind [any] constraint nor upon the lame constraint nor upon the ill constraint …» — is located in the midst of a section describing proper behavior for visiting relations and modesty for women and children («when you eat from your [own] houses or the houses of your fathers or the houses of your mothers or the houses of your brothers or the houses of your sisters or …»). While it makes little sense here, the exact same phrases appears in another surah section (Q.48:11-17) where it does fit in as list of those exempt from blame and hellfire if they do not fight in a jihad military campaign.[79][80][81]

Theodor Nöldeke complains that «many sentences begin with a ‘when’ or ‘on the day when’ which seems to hover in the air, so that commentators are driven to supply a ‘think of this’ or some such ellipsis.»[82] Similarly, describing a «rough edge» of the Quran, Michael Cook notes that verse Q.33:37 starts out with a «long and quite complicated subordinate clause» («when thou wast saying to him …»), «but we never learn what the clause is subordinate to.»[65]

Grammar[edit]

Examples of lapses in grammar include 4:160 where the word «performers» should be in the nominative case but instead is in the accusative; 20:66 where «these two» of «These two are sorcerers» is in the nominative case (hādhāne) instead of the accusative case (hādhayne); and 49:9 where «have started to fight» is in the plural form instead of the dual like the subject of the sentence.[citation needed] Dashti laments that Islamic scholars have traditionally replied to these problems saying «our task is not to make the readings conform to Arabic grammar, but to take the whole of the Quran as it is and make Arabic grammar conform to the Quran.»[citation needed]

Reply[edit]

A common reply to questions about difficulties or obscurities in the Quran is verse 3:7 which unlike other verses that simply state that the Quran is clear (mubeen) states that some verses are clear but others are «ambiguous».

- 3:7 It is He who sent down upon thee the Book, wherein are verses clear that are the Essence of the Book, and others ambiguous. As for those in whose hearts is swerving, they follow the ambiguous part, desiring dissension, and desiring its interpretation; and none knows its interpretation, save only God. And those firmly rooted in knowledge say, ‘We believe in it; all is from our Lord’; yet none remembers, but men possessed of minds.

In regards to questions about the narrative voice, Al-Zarkashi asserts that «moving from one style to another serves to make speech flow more smoothly», but also that by mixing up pronouns the Quran prevents the «boredom» that a more logical, straight forward narrative induces; it keeps the reader on their toes, helping «the listener to focus, renew[ing] his interest», providing «freshness and variety».[83] «Muslim specialists» refer to the practice as iltifāt, («literally ‘conversion’, or ‘turning one’s face to‘«).[83] Western scholar Neal Robinson provides a more detailed reasons as to why these are not «imperfections», but instead should be «prized»: changing the voice from «they» to «we» provides a «shock effect», third person («Him») makes God «seem distant and transcendent», first person plural («we») «emphasizes His majesty and power», first person singular («I») «introduces a note of intimacy or immediacy», and so on.[83]

(Critics like Hassan Radwan suggest these explanations are rationalizations.)[84]

Preexisting sources[edit]

Sami Aldeeb, Palestinian-born Swiss lawyer and author of many books and articles on Arab and Islamic law, holds the theory that the Quran was written by a rabbi.[85] Günter Lüling asserts that one-third of the Quran has pre-Islamic Christian origins.[86] Puin likewise thinks some of the material predates Muhammad’s life.[28]

Scholar Oddbjørn Leirvik states «The Qur’an and Hadith have been clearly influenced by the non-canonical (‘heretical’) Christianity that prevailed in the Arab peninsula and further in Abyssinia» prior to Islam.[87]