Инструменты автоматизации и мониторинга удобны тем, что разработчик может взять готовые скрипты, при необходимости адаптировать и использовать в своём проекте. Можно заметить, что в некоторых скриптах используются коды завершения (exit codes), а в других нет. О коде завершения легко забыть, но это очень полезный инструмент. Особенно важно использовать его в скриптах командной строки.

Что такое коды завершения

В Linux и других Unix-подобных операционных системах программы во время завершения могут передавать значение родительскому процессу. Это значение называется кодом завершения или состоянием завершения. В POSIX по соглашению действует стандарт: программа передаёт 0 при успешном исполнении и 1 или большее число при неудачном исполнении.

Почему это важно? Если смотреть на коды завершения в контексте скриптов для командной строки, ответ очевиден. Любой полезный Bash-скрипт неизбежно будет использоваться в других скриптах или его обернут в однострочник Bash. Это особенно актуально при использовании инструментов автоматизации типа SaltStack или инструментов мониторинга типа Nagios. Эти программы исполняют скрипт и проверяют статус завершения, чтобы определить, было ли исполнение успешным.

Кроме того, даже если вы не определяете коды завершения, они всё равно есть в ваших скриптах. Но без корректного определения кодов выхода можно столкнуться с проблемами: ложными сообщениями об успешном исполнении, которые могут повлиять на работу скрипта.

Что происходит, когда коды завершения не определены

В Linux любой код, запущенный в командной строке, имеет код завершения. Если код завершения не определён, Bash-скрипты используют код выхода последней запущенной команды. Чтобы лучше понять суть, обратите внимание на пример.

#!/bin/bash

touch /root/test

echo created file

Этот скрипт запускает команды touch и echo. Если запустить этот скрипт без прав суперпользователя, команда touch не выполнится. В этот момент мы хотели бы получить информацию об ошибке с помощью соответствующего кода завершения. Чтобы проверить код выхода, достаточно ввести в командную строку специальную переменную $?. Она печатает код возврата последней запущенной команды.

$ ./tmp.sh

touch: cannot touch '/root/test': Permission denied

created file

$ echo $?

0

Как видно, после запуска команды ./tmp.sh получаем код завершения 0. Этот код говорит об успешном выполнении команды, хотя на самом деле команда не выполнилась. Скрипт из примера выше исполняет две команды: touch и echo. Поскольку код завершения не определён, получаем код выхода последней запущенной команды. Это команда echo, которая успешно выполнилась.

Скрипт:

#!/bin/bash

touch /root/test

Если убрать из скрипта команду echo, можно получить код завершения команды touch.

$ ./tmp.sh

touch: cannot touch '/root/test': Permission denied

$ echo $?

1

Поскольку touch в данном случае — последняя запущенная команда, и она не выполнилась, получаем код возврата 1.

Как использовать коды завершения в Bash-скриптах

Удаление из скрипта команды echo позволило нам получить код завершения. Что делать, если нужно сделать разные действия в случае успешного и неуспешного выполнения команды touch? Речь идёт о печати stdout в случае успеха и stderr в случае неуспеха.

Проверяем коды завершения

Выше мы пользовались специальной переменной $?, чтобы получить код завершения скрипта. Также с помощью этой переменной можно проверить, выполнилась ли команда touch успешно.

#!/bin/bash

touch /root/test 2> /dev/null

if [ $? -eq 0 ]

then

echo "Successfully created file"

else

echo "Could not create file" >&2

fi

После рефакторинга скрипта получаем такое поведение:

- Если команда

touchвыполняется с кодом0, скрипт с помощьюechoсообщает об успешно созданном файле. - Если команда

touchвыполняется с другим кодом, скрипт сообщает, что не смог создать файл.

Любой код завершения кроме 0 значит неудачную попытку создать файл. Скрипт с помощью echo отправляет сообщение о неудаче в stderr.

Выполнение:

$ ./tmp.sh

Could not create file

Создаём собственный код завершения

Наш скрипт уже сообщает об ошибке, если команда touch выполняется с ошибкой. Но в случае успешного выполнения команды мы всё также получаем код 0.

$ ./tmp.sh

Could not create file

$ echo $?

0

Поскольку скрипт завершился с ошибкой, было бы не очень хорошей идеей передавать код успешного завершения в другую программу, которая использует этот скрипт. Чтобы добавить собственный код завершения, можно воспользоваться командой exit.

#!/bin/bash

touch /root/test 2> /dev/null

if [ $? -eq 0 ]

then

echo "Successfully created file"

exit 0

else

echo "Could not create file" >&2

exit 1

fi

Теперь в случае успешного выполнения команды touch скрипт с помощью echo сообщает об успехе и завершается с кодом 0. В противном случае скрипт печатает сообщение об ошибке при попытке создать файл и завершается с кодом 1.

Выполнение:

$ ./tmp.sh

Could not create file

$ echo $?

1

Как использовать коды завершения в командной строке

Скрипт уже умеет сообщать пользователям и программам об успешном или неуспешном выполнении. Теперь его можно использовать с другими инструментами администрирования или однострочниками командной строки.

Bash-однострочник:

$ ./tmp.sh && echo "bam" || (sudo ./tmp.sh && echo "bam" || echo "fail")

Could not create file

Successfully created file

bam

В примере выше && используется для обозначения «и», а || для обозначения «или». В данном случае команда выполняет скрипт ./tmp.sh, а затем выполняет echo "bam", если код завершения 0. Если код завершения 1, выполняется следующая команда в круглых скобках. Как видно, в скобках для группировки команд снова используются && и ||.

Скрипт использует коды завершения, чтобы понять, была ли команда успешно выполнена. Если коды завершения используются некорректно, пользователь скрипта может получить неожиданные результаты при неудачном выполнении команды.

Дополнительные коды завершения

Команда exit принимает числа от 0 до 255. В большинстве случаев можно обойтись кодами 0 и 1. Однако есть зарезервированные коды, которые обозначают конкретные ошибки. Список зарезервированных кодов можно посмотреть в документации.

Адаптированный перевод статьи Understanding Exit Codes and how to use them in bash scripts by Benjamin Cane. Мнение администрации Хекслета может не совпадать с мнением автора оригинальной публикации.

����� 6. ���������� � ��� ����������

| � |

…��� ����� Bourne shell ������� ������, ��� �� |

| � | Chet Ramey |

������� exit ����� �������������� ���

���������� ������ ��������, ����� ��� �� ��� � � ���������� ��

����� C. ����� ����, ��� ����� ���������� ��������� ��������,

������� ����� ���� ���������������� ���������� ���������.

������ ������� ���������� ��� ���������� (������ ��� ����������

�������� ������������ ��������� ). � ������ ������

������� ������ ���������� 0, � � ������ ������ — ��������� ��������, �������, ���

�������, ���������������� ��� ��� ������. ����������� ��� �������

� ������� UNIX ���������� 0 � ������ ��������� ����������, ��

������� � ���������� �� ������.

����������� ������� ����� ���� �������, ������������� ������

��������, � ��� ��������, ��������� ��� ����������. ���,

������������ �������� ��� ���������, ������������ ����� ��������

��������� �������. ������� exit ����� ���� �������

��� ��������, � ����: exit nnn, ��� nnn — ��� ��� ��������

(����� � ��������� 0 — 255).

|

����� ������ �������� ����������� �������� exit ��� ����������, �� ��� |

��� �������� ��������� ������� �������� � �����������

���������� $?. ����� ���������� ���� �������,

���������� $? ������ ��� ���������� ��������� �������,

����������� � �������. ����� �������� � Bash ���������� «��������, ������������»

��������. ����� ���������� ������ ��������, ��� �������� �����

��������, ����������� �� ��������� ������ � ���������� $?, �.�. ��� ����� ��� �������� ���������

�������, ����������� � ��������.

������ 6-1. ���������� / ��� ����������

#!/bin/bash

echo hello

echo $? # ��� �������� = 0, ��������� ������� ����������� �������.

lskdf # �������������� �������.

echo $? # ��������� ��� ��������, ��������� ������� ��������� �� �������.

echo

exit 113 # ����� �������� ���� �������� 113.

# ��������� �����, ���� ������� � ��������� ������ "echo $?"

# ����� ���������� ����� �������.

# � ������������ � ������������, 'exit 0' ��������� �� �������� ����������,

#+ � �� ����� ��� ��������� �������� �������� ������.

���������� $? �������� �������, �����

���������� ��������� ��������� ���������� ������� (��. ������ 12-27 � ������ 12-13).

|

������ !, ����� ��������� ��� ������ 6-2. ������������� ������� ! ��� ���������� �������� ���� true # ���������� ������� "true". echo "��� �������� ������� \"true\" = $?" # 0 ! true echo "��� �������� ������� \"! true\" = $?" # 1 # �������� ��������: ������ "!" �� ������� ���������� �������� ��������. # !true ������� ��������� �� ������ "command not found" # ������� S.C. |

When a bash command is executed, it leaves behind the exit code, irrespective of successful or unsuccessful execution. Examining the exit code can offer useful insight into the behavior of the last-run command.

In this guide, check out how to check bash exit code of the last command and some possible usages of it.

Every UNIX/Linux command executed by the shell script or user leaves an exit status. It’s an integer number that remains unchanged unless the next command is run. If the exit code is 0, then the command was successful. If the exit code is non-zero (1-255), then it signifies an error.

There are many potential usages of the bash exit code. The most obvious one is, of course, to verify whether the last command is executed properly, especially if the command doesn’t generate any output.

In the case of bash, the exit code of the previous command is accessible using the shell variable “$?”.

Checking Bash Exit Code

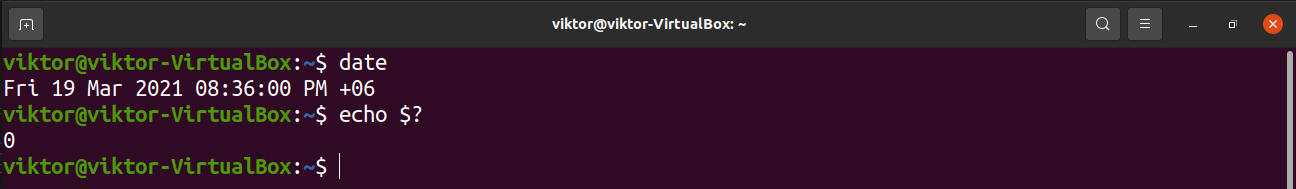

Launch a terminal, and run any command.

Check the value of the shell variable “$?” for the exit code.

As the “date” command ran successfully, the exit code is 0. What would happen if there was an error?

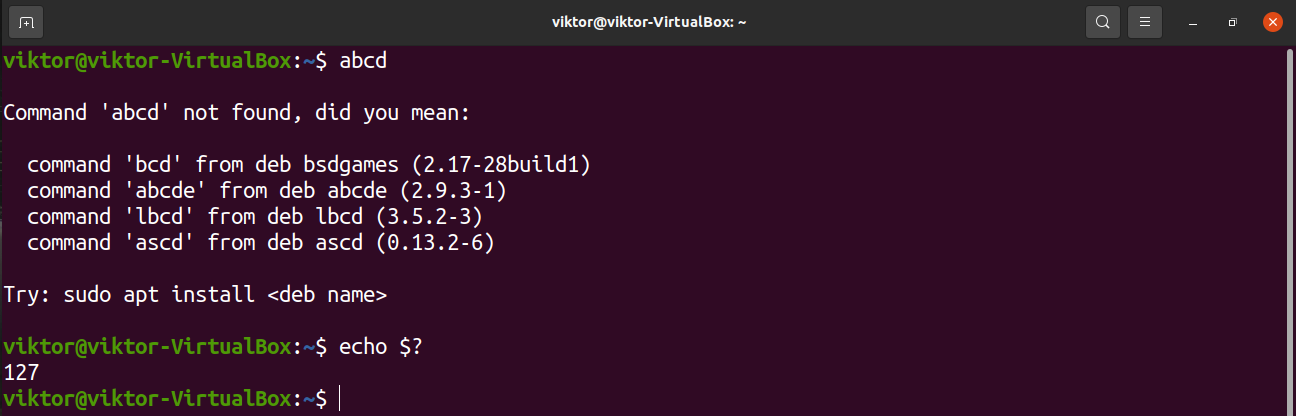

Let’s try running a command that doesn’t exist.

Check the exit code.

It’s a non-zero value, indicating that the previous command didn’t execute properly.

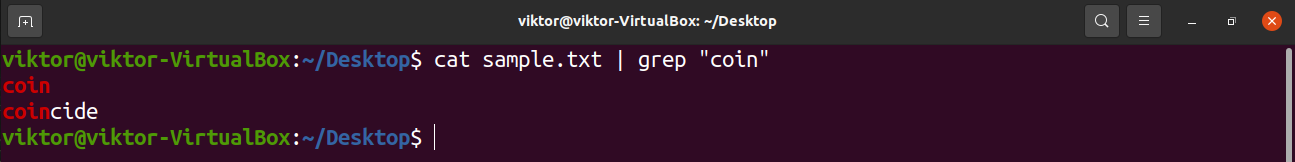

Now, have a look at the following command:

$ cat sample.txt | grep “coin”

When working with a command that has one or more pipes, the exit code will be of the last code executed in the pipe. In this case, it’s the grep command.

As the grep command was successful, it will be 0.

In this example, if the grep command fails, then the exit code will be non-zero.

$ cat sample.txt | grep “abcd”

$ echo $?

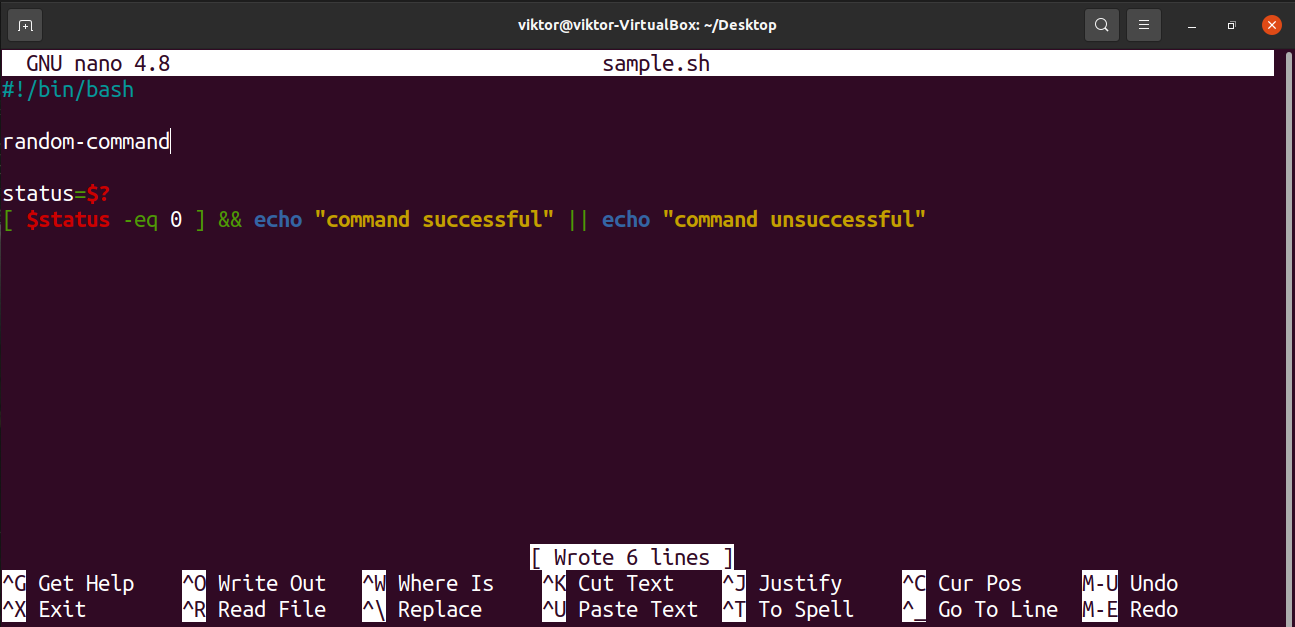

Incorporating Exit Code in Scripts

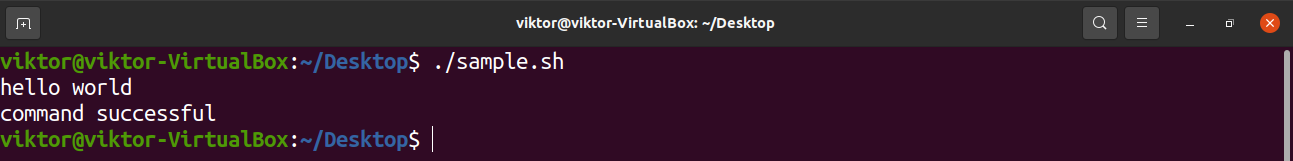

The exit code can also be used for scripting. One simple way to use it is by assigning it to a shell variable and working with it. Here’s a sample shell script that uses the exit code as a condition to print specific output.

$ #!/bin/bash

$ echo «hello world»

$ status=$?

$ [ $status -eq 0 ] && echo «command successful» || echo «command unsuccessful»

When being run, the script will generate the following output.

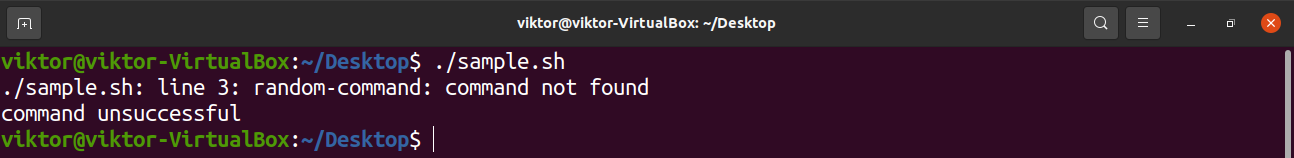

Now, let’s see what happens when there’s an invalid command to run.

$ #!/bin/bash

$ random-command

$ status=$?

$ [ $status -eq 0 ] && echo «command successful» || echo «command unsuccessful»

When being run, the output will be different.

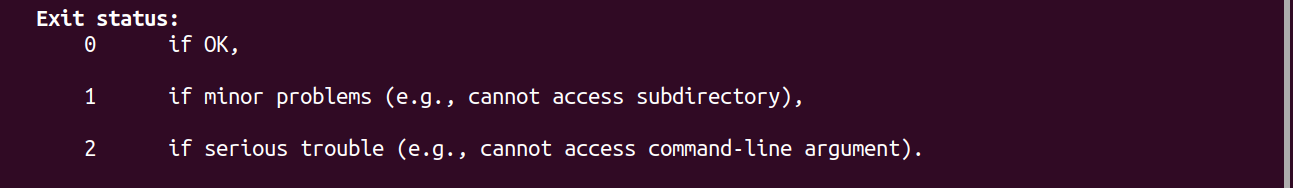

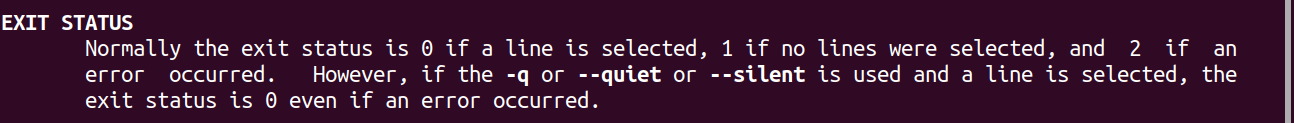

Exit Code Value Explanation

When the exit code is non-zero, the value ranges from 1 to 255. Now, what does this value mean?

While the value is limited, the explanation of each value is unique to the program/script. For example, “ls” and “grep” has different explanations for error code 1 and 2.

Defining Exit Status in Script

When writing a script, we can define custom exit code values. It’s a useful method for easier debugging. In bash scripts, it’s the “exit” command followed by the exit code value.

Per the convention, it’s recommended to assign exit code 0 for successful execution and use the rest (1-255) for possible errors. When reaching the exit command, the shell script execution will be terminated, so be careful of its placement.

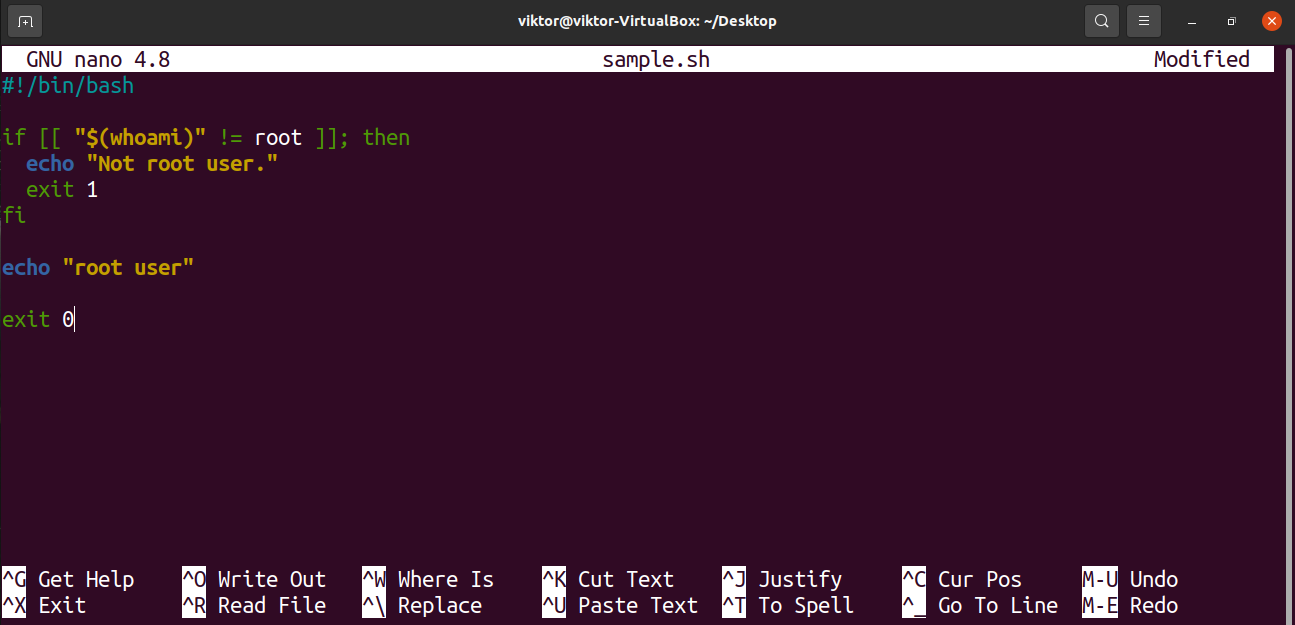

Have a look at the following shell script. Here, if the condition is met, the script will terminate with the exit code 0. If the condition isn’t met, then the exit code will be 1.

$ #!/bin/bash

$ if [[ «$(whoami)« != root ]]; then

$ echo «Not root user.»

$ exit 1

$ fi

$ echo «root user»

$ exit 0

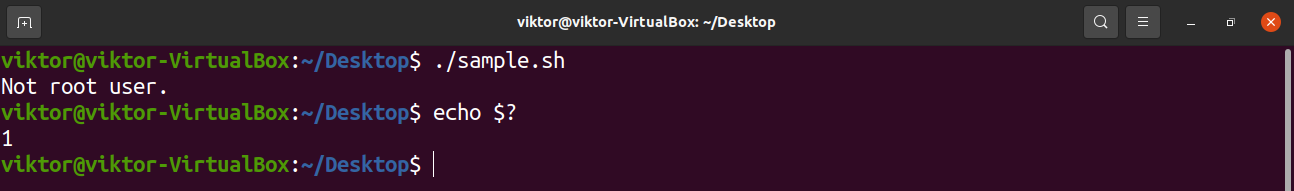

Verify the result of running this script without sudo privilege or “root” user.

Final Thoughts

This guide demonstrates what exit codes are and how you can use them. It also demonstrates how to assign appropriate exit codes in a bash script.

Interested in bash scripting? One of the easiest ways to get started is by writing your own scripts. Check out this simple guide on how to write a simple bash script.

Happy computing!

About the author

Student of CSE. I love Linux and playing with tech and gadgets. I use both Ubuntu and Linux Mint.

When you execute a command or run a script, you receive an exit code. An exit code is a system response that reports success, an error, or another condition that provides a clue about what caused an unexpected result from your command or script. Yet, you might never know about the code, because an exit code doesn’t reveal itself unless someone asks it to do so. Programmers use exit codes to help debug their code.

Note: You’ll often see exit code referred to as exit status or even as exit status codes. The terms are used interchangeably except in documentation. Hopefully my use of the two terms will be clear to you.

I’m not a programmer. It’s hard for me to admit that, but it’s true. I’ve studied BASIC, FORTRAN, and a few other languages both formally and informally, and I have to say that I am definitely not a programmer. Oh sure, I can script and program a little in PHP, Perl, Bash, and even PowerShell (yes, I’m also a Windows administrator), but I could never make a living at programming because I’m too slow at writing code and trial-and-error isn’t an efficient debugging strategy. It’s sad, really, but I’m competent enough at copying and adapting found code that I can accomplish my required tasks. And yet, I also use exit codes to figure out where my problems are and why things are going wrong.

[ You might also like: A little SSH file copy magic at the command line. ]

Exit codes are useful to an extent, but they can also be vague. For example, an exit code of 1 is a generic bucket for miscellaneous errors and isn’t helpful at all. In this article, I explain the handful of reserved error codes, how they can occur, and how to use them to figure out what your problem is. A reserved error code is one that’s used by Bash and you shouldn’t create your own error codes that conflict with them.

Enough backstory. It’s time to look at examples of what generates error codes/statuses.

Extracting the elusive exit code

To display the exit code for the last command you ran on the command line, use the following command:

$ echo $?The displayed response contains no pomp or circumstance. It’s simply a number. You might also receive a shell error message from Bash further describing the error, but the exit code and the shell error together should help you discover what went wrong.

Exit status 0

An exit status of 0 is the best possible scenario, generally speaking. It tells you that your latest command or script executed successfully. Success is relative because the exit code only informs you that the script or command executed fine, but the exit code doesn’t tell you whether the information from it has any value. Examples will better illustrate what I’m describing.

For one example, list files in your home directory. I have nothing in my home directory other than hidden files and directories, so nothing to see here, but the exit code doesn’t care about anything but the success of the command’s execution:

$ ls

$ echo $?

0

The exit code of 0 means that the ls command ran without issue. Although, again, the information from exit code provides no real value to me.

Now, execute the ls command on the /etc directory and then display the exit code:

$ ls /etc

**Many files**

$ echo $?

0You can see that any successful execution results in an exit code of 0, including something that’s totally wrong, such as issuing the cat command on a binary executable file like the ls command:

$ cat /usr/bin/ls

**A lot of screen gibberish and beeping**

$ echo $?

0Exit status 1

Using the above example but adding in the long listing and recursive options (-lR), you receive a new exit code of 1:

$ ls -lR /etc

**A lengthy list of files**

$ echo $?

1Although the command’s output looks as though everything went well, if you scroll up you will see several «Permission denied» errors in the listing. These errors result in an exit status of 1, which is described as «impermissible operations.» Although you might expect that a «Permission denied» error leads to an exit status of 1, you’d be wrong, as you will see in the next section.

Dividing by zero, however, gives you an exit status of 1. You also receive an error from the shell to let you know that the operation you’re performing is «impermissible:»

$ let a=1

$ let b=0

$ let c=a/b

-bash: let: c=a/b: division by 0 (error token is "b")

$ echo $?

1

Without a shell error, an exit status of 1 isn’t very helpful, as you can see from the first example. In the second example, you know why you received the error because Bash tells you with a shell error message. In general, when you receive an exit status of 1, look for the impermissible operations (Permission denied messages) mixed with your successes (such as listing all the files under /etc, as in the first example in this section).

Exit status 2

As stated above, a shell warning of «Permission denied» results in an exit status of 2 rather than 1. To prove this to yourself, try listing files in /root:

$ ls /root

ls: cannot open directory '/root': Permission denied

$ echo $?

2

Exit status 2 appears when there’s a permissions problem or a missing keyword in a command or script. A missing keyword example is forgetting to add a done in a script’s do loop. The best method for script debugging with this exit status is to issue your command in an interactive shell to see the errors you receive. This method generally reveals where the problem is.

Permissions problems are a little less difficult to decipher and debug than other types of problems. The only thing «Permission denied» means is that your command or script is attempting to violate a permission restriction.

Exit status 126

Exit status 126 is an interesting permissions error code. The easiest way to demonstrate when this code appears is to create a script file and forget to give that file execute permission. Here’s the result:

$ ./blah.sh

-bash: ./blah.sh: Permission denied

$ echo $?

126

This permission problem is not one of access, but one of setting, as in mode. To get rid of this error and receive an exit status of 0 instead, issue chmod +x blah.sh.

Note: You will receive an exit status of 0 even if the executable file has no contents. As stated earlier, «success» is open to interpretation.

I receiving an exit status of 126. This code actually tells me what’s wrong, unlike the more vague codes.

Exit status 127

Exit status 127 tells you that one of two things has happened: Either the command doesn’t exist, or the command isn’t in your path ($PATH). This code also appears if you attempt to execute a command that is in your current working directory. For example, the script above that you gave execute permission is in your current directory, but you attempt to run the script without specifying where it is:

$ blah.sh

-bash: blah.sh: command not found

$ echo $?

127

If this result occurs in a script, try adding the explicit path to the problem executable or script. Spelling also counts when specifying an executable or a script.

[ Readers also enjoyed: 10 basic Linux commands you need to know. ]

Exit status 128

Exit status 128 is the response received when an out-of-range exit code is used in programming. From my experience, exit status 128 is not possible to produce. I have tried multiple actions for an example, and I can’t make it happen. However, I can produce an exit status 128-adjacent code. If your exit code exceeds 256, the exit status returned is your exit code subtracted by 256. This result sounds odd and can actually create an incorrect exit status. Check the examples to see for yourself.

Using an exit code of 261, create an exit status of 5:

$ bash

$ exit 261

exit

$ echo $?

5

To produce an errant exit status of 0:

$ bash

$ exit 256

exit

$ echo $?

0

If you use 257 as the exit code, your exit status is 1, and so on. If the exit code is a negative number, the resulting exit status is that number subtracted from 256. So, if your exit code is 20, then the exit status is 236.

Troubling, isn’t it? The solution, to me, is to avoid using exit codes that are reserved and out-of-range. The proper range is 0-255.

Exit status 130

If you’re running a program or script and press Ctrl-C to stop it, your exit status is 130. This status is easy to demonstrate. Issue ls -lR / and then immediately press Ctrl-C:

$ ls -lR /

**Lots of files scrolling by**

^C

$ echo $?

130

There’s not much else to say about this one. It’s not a very useful exit status, but here it is for your reference.

Exit status 255

This final reserved exit status is easy to produce but difficult to interpret. The documentation that I’ve found states that you receive exit status 255 if you use an exit code that’s out of the range 0-255.

I’ve found that this status can also be produced in other ways. Here’s one example:

$ ip

**Usage info for the ip command**

$ echo $?

255

Some independent authorities say that 255 is a general failure error code. I can neither confirm nor deny that statement. I only know that I can produce exit status 255 by running particular commands with no options.

[ Related article: 10 more essential Linux commands you need to know. ]

Wrapping up

There you have it: An overview of the reserved exit status numbers, their meanings, and how to generate them. My personal advice is to always check permissions and paths for anything you run, especially in a script, instead of relying on exit status codes. My debug method is that when a command doesn’t work correctly in a script, I run the command individually in an interactive shell. This method works much better than trying fancy tactics with breaks and exits. I go this route because (most of the time) my errors are permissions related, so I’ve been trained to start there.

Have fun checking your statuses, and now it’s time for me to exit.

[ Want to try out Red Hat Enterprise Linux? Download it now for free. ]

Exit codes indicates a failure condition when ending a program and they fall between 0 and 255. The shell and its builtins may use especially the values above 125 to indicate specific failure modes, so list of codes can vary between shells and operating systems (e.g. Bash uses the value 128+N as the exit status). See: Bash — 3.7.5 Exit Status or man bash.

In general a zero exit status indicates that a command succeeded, a non-zero exit status indicates failure.

To check which error code is returned by the command, you can print $? for the last exit code or ${PIPESTATUS[@]} which gives a list of exit status values from pipeline (in Bash) after a shell script exits.

There is no full list of all exit codes which can be found, however there has been an attempt to systematize exit status numbers in kernel source, but this is main intended for C/C++ programmers and similar standard for scripting might be appropriate.

Some list of sysexits on both Linux and BSD/OS X with preferable exit codes for programs (64-78) can be found in /usr/include/sysexits.h (or: man sysexits on BSD):

0 /* successful termination */

64 /* base value for error messages */

64 /* command line usage error */

65 /* data format error */

66 /* cannot open input */

67 /* addressee unknown */

68 /* host name unknown */

69 /* service unavailable */

70 /* internal software error */

71 /* system error (e.g., can't fork) */

72 /* critical OS file missing */

73 /* can't create (user) output file */

74 /* input/output error */

75 /* temp failure; user is invited to retry */

76 /* remote error in protocol */

77 /* permission denied */

78 /* configuration error */

/* maximum listed value */

The above list allocates previously unused exit codes from 64-78. The range of unallotted exit codes will be further restricted in the future.

However above values are mainly used in sendmail and used by pretty much nobody else, so they aren’t anything remotely close to a standard (as pointed by @Gilles).

In shell the exit status are as follow (based on Bash):

-

1—125— Command did not complete successfully. Check the command’s man page for the meaning of the status, few examples below: -

1— Catchall for general errorsMiscellaneous errors, such as «divide by zero» and other impermissible operations.

Example:

$ let "var1 = 1/0"; echo $? -bash: let: var1 = 1/0: division by 0 (error token is "0") 1 -

2— Misuse of shell builtins (according to Bash documentation)Missing keyword or command, or permission problem (and diff return code on a failed binary file comparison).

Example:

empty_function() {} -

6— No such device or addressExample:

$ curl foo; echo $? curl: (6) Could not resolve host: foo 6 -

124— command times out 125— if a command itself failssee: coreutils-

126— if command is found but cannot be invoked (e.g. is not executable)Permission problem or command is not an executable.

Example:

$ /dev/null $ /etc/hosts; echo $? -bash: /etc/hosts: Permission denied 126 -

127— if a command cannot be found, the child process created to execute it returns that statusPossible problem with

$PATHor a typo.Example:

$ foo; echo $? -bash: foo: command not found 127 -

128— Invalid argument toexitexit takes only integer args in the range 0 — 255.

Example:

$ exit 3.14159 -bash: exit: 3.14159: numeric argument required -

128—254— fatal error signal «n» — command died due to receiving a signal. The signal code is added to 128 (128 + SIGNAL) to get the status (Linux:man 7 signal, BSD:man signal), few examples below: -

130— command terminated due to Ctrl-C being pressed, 130-128=2 (SIGINT)Example:

$ cat ^C $ echo $? 130 -

137— if command is sent theKILL(9)signal (128+9), the exit status of command otherwisekill -9 $PPIDof script. -

141—SIGPIPE— write on a pipe with no readerExample:

$ hexdump -n100000 /dev/urandom | tee &>/dev/null >(cat > file1.txt) >(cat > file2.txt) >(cat > file3.txt) >(cat > file4.txt) >(cat > file5.txt) $ find . -name '*.txt' -print0 | xargs -r0 cat | tee &>/dev/null >(head /dev/stdin > head.out) >(tail /dev/stdin > tail.out) xargs: cat: terminated by signal 13 $ echo ${PIPESTATUS[@]} 0 125 141 -

143— command terminated by signal code 15 (128+15=143)Example:

$ sleep 5 && killall sleep & [1] 19891 $ sleep 100; echo $? Terminated: 15 143 -

255* — exit status out of range.exit takes only integer args in the range 0 — 255.

Example:

$ sh -c 'exit 3.14159'; echo $? sh: line 0: exit: 3.14159: numeric argument required 255

According to the above table, exit codes 1 — 2, 126 — 165, and 255 have special meanings, and should therefore be avoided for user-specified exit parameters.

Please note that out of range exit values can result in unexpected exit codes (e.g. exit 3809 gives an exit code of 225, 3809 % 256 = 225).

See:

- Appendix E. Exit Codes With Special Meanings at Advanced Bash-Scripting Guide

- Writing Better Shell Scripts – Part 2 at Innovationsts